Douglas T. Summerfield, MD

Kelly Cawcutt, MD

Robert Van Demark, MD

Matthew J. Ritter, MD

Departments of Anesthesia and Pulmonary/Critical Care Medicine

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, MN

Case Report

A 77 year old female with a past medical history of dementia, chronic atrial fibrillation requiring anticoagulation, hypertension, biventricular congestive heart failure with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction, pulmonary hypertension, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) presented to the emergency room after she sustained a ground level fall while sitting in a chair. The patient reportedly fell asleep while sitting at the kitchen table, and subsequently fell to her right side. According to witnesses, she did not strike her head, and there was no observed loss of consciousness. As part of her initial evaluation, at an outside hospital, radiographs of the pelvis, hip, and knee were obtained. These identified a definitive right superior pubic ramus fracture with inferior displacement and a questionable fracture of the right femoral neck. Shortly thereafter, the patient was transferred to our hospital for further management. On exam, the patient had a painful right hip limiting active motion and her right lower extremity was neurovascularly intact without paresthesias or dysesthesias. The remainder of the exam was unremarkable. In the emergency room, a repeat radiograph showed no evidence of a right femur fracture. Later in the evening a CT scan of the pelvis with intravenous contrast showed acute fractures through the right superior and inferior pubic rami with associated hematoma. Multiple tiny bony fragments were noted adjacent to the superior pubic ramus fracture (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CT scan demonstrating acute fractures through the superior and inferior pubic rami with associated hematoma. Multiple tiny bone fragments are adjacent to the superior pubic ramus fracture.

The CT did not show an apparent femur fracture. MRI of the pelvis and hip were ordered to assess for a femoral fracture; however this was not obtained secondary to patient confusion thus no quality diagnostic images were produced. The orthopedic service concluded that surgery was not required for the stable, type 1 lateral compression injury that resulted from the fall.

The patient was admitted to a general medicine floor for non-surgical management which included weight bearing as tolerated as well as therapy with physical medicine and rehabilitation. On admission, her vital signs were stable, including a heart rate of 89, blood pressure of 159/89, respirations of 20, with the exception of her peripheral oxygen saturation which was 89% on room air. Over the next several hospital days, she continued to have low oxygen saturations, began requiring fluid boluses to maintain an adequate mean arterial blood pressure (secondary to systolic blood pressure falling to the 70-80mmHg range intermittently) and she developed acute kidney injury with her creatinine increasing to 4.2 from her baseline of 1.1. Nephrology was consulted to evaluate the acute kidney injury and their impression was acute renal failure secondary to contrast administration for the initial CT scan, in the setting of chronic spironolactone and furosemide use. The patient’s mental status remained altered, her speech although typically understandable was non-coherent, and she remained bed-bound. Due to her underlying dementia, her baseline mental status was difficult to determine and this combined with her opioids for pain control were felt to contribute to her mental status.

During her first dialysis session, the patient developed hypotension and hypoxemia which necessitated a rapid response call and transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU). The impression at the time of transfer to the ICU was septic shock with multi-organ dysfunction syndrome, presumably from a urinary source. The initial exam by the ICU team demonstrated what was thought to be considerable acute mental status change with agitation and moaning, hypotension, hypoxemia, and continued renal failure. Further review of her hospital course revealed that these changes had slowly been progressing since admission. Stabilization in the ICU included placement of a right internal jugular central venous catheter, blood pressure support with vasopressors, as well as intubation and high level of ventilatory support, including inhaled alprostadil, for severe hypoxemic respiratory failure. In addition, she was also placed on continuous renal replacement therapy.

In order to better assess the patient’s fluid status, the service fellow assessed the vena cava with the bedside ultrasound. While observing the collapsibility of the IVC, small hyperechoic spheres were observed traveling through the IVC proximally towards the right heart. A subcostal window focusing on the right ventricle demonstrated the same hyperechoic spheres whirling within the right ventricle. These same spheres were seen in both the four chamber view (Figure 2), as well as the short axis view and were present for several hours.

Figure 2. Four chambered view revealing right ventricular bowing as well as small hyperechoic spheres present in the right ventricle and atria.

Two hours later, a formal bedside echocardiogram was performed to evaluate the right heart structure and function. The estimated right ventricular systolic pressure was at 70 mm Hg, indicating severe pulmonary hypertension. The right ventricle was enlarged, and there was severe tricuspid regurgitation. Again there continued to be small hyperechoic spheres within her right ventricle as well as her right atria. Per the formal cardiologist reading, these were consistent with fat emboli. Further laboratory evaluation, including the presence of urinary fat, helped confirm the diagnosis of fat emboli syndrome.

Supportive care was continued, but without obvious improvement. After a family care conference, she was transitioned to palliative care and died.

Background

Fat emboli (FE) and fat emboli syndrome (FES) have been described clinically and pathologically since the 1860’s. Early work by Zenker in 1862 first described the pathologic significance of fat embolism with the link of fat to bone marrow release during fractures was discovered by Wagner in 1865. Despite the 150 years since its discovery, the diagnosis of Fat Embolism remains elusive. FE is quite common with the presence of intravascular pulmonary fat seen in greater than 90% of patients with skeletal trauma at autopsy (1). However, the presence of pulmonary fat alone does not necessarily mean the patient will develop FES. In a case series of 51 medical and surgical ICU patients, FE was identified in 28 (51%) of patients, none of whom had classic manifestations of FES (2).

The three major components of FES have classically consisted of the triad of petechial rash, progressive respiratory failure, and neurologic deterioration. The incidence following orthopedic procedures ranges from 0.25% to 35% (3). The wide variation of the reported incidence may in part be due to the fact that FES can affect almost every organ system and the classic symptoms are only present either transiently or in varying degrees, and may not manifest for 12-72 hours after the initial insult (4). The patient we present represents both the lack of the classic triad and the delayed onset of signs and symptoms, illustrating the elusiveness of the diagnosis.

Of the major clinical criteria, the cardio-pulmonary symptoms are the most clinically significant. Symptoms occur in up to 75% of patients with FES and range from mild hypoxemia to ARDS and/or acute cor pulmonale. The timing of symptoms may coincide with manipulation of a fracture, and there have been numerous reports of this occurring intraoperatively with direct visualization of fat emboli seen on trans-esophageal echo (TEE) (5-8).

The classic petechial rash, which was not noted in our patient, is typically seen on the upper anterior torso, oral mucosa, and conjunctiva. It is usually resolved within 24 hours and has been attributed to dermal vessel engorgement, endothelial fragility, and platelet damage all from the release of free fatty acids (9). The clinical manifestation of this “classic” finding varies widely and has been reported in 25-95% of the cases (4, 10).

Neurologic dysfunction can range from headache to seizure and coma and is thought to be secondary to cerebral edema due to multifactorial insults. These neurologic changes are seen in up to 86% of patients, and on MRI produce multiple small, non-confluent hyper intensities that appear within 30 minutes of injury. The number and size correlate to GCS, and subsequently reversal of the lesions is seen during neurologic recovery. (11,12).

Temporary CNS dysfunction usually occurs 24-72 hours after initial injury and acute loss of consciousness immediately post-operatively has been documented. Of note, this loss of consciousness may not be a catastrophic event. In a case report by Nandi et al., a patient with acute loss of consciousness made full neurologic recovery within four hours (13). In the retina, direct evidence of FE and FES manifests as cotton-wool spots and flame-like hemorrhages (1). However these findings are only detected in 50% of patient with FES (14)

FES also affects the hematological system, producing anemia and thrombocytopenia 37% and 67% of the time, respectively (15, 16). Thrombocytopenia is correlated to an increased A-a gradient, which Akhtar et al. noted that some clinicians include this finding in the criteria to diagnose FES (1).

Diagnosis

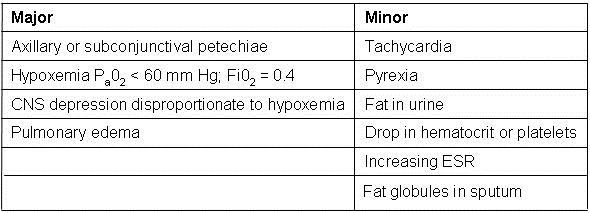

Given the broad and varying manifestations of FES, others have broadened the criteria. The Lindeque criteria require a femur fracture. The FES Index is a scoring system which includes vitals, radiographic findings, and blood gas results. Weisz and colleagues include laboratory values such as fat macroglobulenemia and serum lipid changes. Miller and colleagues (17) even proposed an autopsy diagnosis using histopathic samples. The most widely used criteria are set forth by Gurd and Wilson and require two out of three major criteria be met, or one major plus four out of five minor criteria. Major criteria include pulmonary symptoms, petechial rash, and neurological symptoms. Minor criteria include pyrexia, tachycardia, jaundice, platelet drop by >50%, elevated ESR, retinal changes, renal dysfunction, presence of urinary or sputum fat, and fat macroglobulinemia (1). Of note, none of the proposed diagnostic criteria include direct visualization of fat emboli via ultrasound or echocardiography (18-22) (Table 1).

Table 1: Gurd's Criteria for Diagnosis of FES

Gurd AR. Fat embolism: an aid to diagnosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1970;52(4):732-7. [PubMed]

Mechanism

Two theories explain the systemic symptoms seen in FES. The mechanical theory describes how intramedullary free fat is released into the venous circulation directly from the fracture site or from increased intramedullary pressure during an orthopedic procedure. The basis for the theory is that the fat particles produce mechanical obstruction. However, not all fat emboli translocated into the circulation are harmful. It is estimated that fat particles larger than 8 μm embolize (23-25). As they accumulate in the lungs, aggregates larger than 20 μm occlude the pulmonary vasculature (26). Particles 7-10 μm particles can cross pulmonary capillary beds to affect the skin, brain, and kidneys. On a larger scale, the embolized free fatty acids produce ischemia and the subsequent release of inflammatory markers (27). The mechanism of this systemic spread beyond the pulmonary capillaries is not well understood. Patients without a patent foramen ovale or proven pulmonary shunt develop FES (28). Interestingly enough, other patients with a large fat emboli burden in the pulmonary microvasculature have not progressed to FES (29). One possible explanation for this may be elevated right-sided pressures force pulmonary fat into systemic circulation (1).

The biochemical theory has also been proposed to explain the systemic organ damage. The mechanism describes that enzymatic degradation of fat particles in the blood stream brings about the release of free fatty acids (FFA) (30, 31). FFA and the toxic intermediaries then cause direct injury on the lung and other organs. The fact that many of the symptoms are seen much later than the initial injury would support the Biochemical Theory. This theory also has an obstructive component to it as it recognizes that large fat particles coalesce to obstruct pulmonary capillary beds (11).

Discussion

Fat emboli syndrome is a rare and difficult clinical diagnosis. Currently there is no diagnostic test for FES and even the reported incidence is quite variable. The wide clinical presentation of FES makes the diagnosis challenge, and classic pulmonary involvement does not always occur (31). Furthermore, the symptoms overlap with other illness such as infection, as it did in this patient who was initially thought to be septic. The delayed onset of symptoms may further confound its identification. Finally, the traditional criteria used to diagnosis FES are variable depending on which source is referenced. Case-in-point is the Lindque criteria which require the presence of a femur fracture. By this requirement the patient presented in this case would not have been diagnosed with FES as she presented with a pelvic fracture.

The patient in this case was likely suffering from undiagnosed FES from the time of her admission. Since it did not present in the classic fashion, her progressive respiratory failure and neurologic deterioration were incorrectly attributed to congestive heart failure and opioid administration.

In this patient, the diagnosis of FE was somewhat unexpected, although it was within the differential. For this case the implementation of bedside ultrasound proved critical to the correct diagnosis and subsequent outcome. Instead of following other possible diagnoses and treatment options such as sepsis in this tachycardic, hypotensive patient, supportive care was employed with the diagnosis of fat embolism in mind.

The use of ultrasound imaging is not well studied for the diagnosis of FES, however it may provide an additional tool for making this difficult diagnosis when the classic triad of rash, cardiopulmonary symptoms, and neurologic changes is not seen or is in doubt. When used to evaluate for cardiogenic causes of acute hypotension, bedside cardiac ultrasound may reveal findings suggestive of FES, as it did in this case.

Review of the literature (5-8) confirms similar echogenic findings from fat emboli as seen by TEE intraoperatively during orthopedic procedures. However, similar spheres can be seen in a number of other instances. Infusion of blood products, such as packed red blood cells, may create similar acoustic images. No blood products had been given to the patient at the time of the bedside ultrasound. Additionally cardiologists have traditionally used agitated saline to look for patent foramen ovale. This and air embolism after placement of a central venous catheter can both produce similar images. In this case the emboli were seen traveling through the inferior vena cava, inferior and distal to the right side of the heart. The right internal jugular catheter would not have showered air emboli to that location, additionally once these were seen circulating in the right ventricle, the first action performed was to ensure all ports on the central line were secure. Given that these hyperechoic spheres were present for hours, air emboli would be less likely to be the underlying etiology. The images were later seen during the formal cardiac echo, and again validated by the cardiologist as being consistent with fat emboli.

To our knowledge this is the first case report of critical care bedside echocardiography (BE), assisting with the diagnosis of fat emboli syndrome. This is in contrast to TEE which has been used to diagnose FE and presumed FES in hemodynamically unstable patients in the operating room (5-8).

BE is attractive as it requires less training than TEE and can be repeated at the bedside as the clinical picture changes. By itself BE cannot differentiate FE from FES, but since the practitioner using it is presumably familiar with the patient’s condition, it can be used to augment the diagnosis when other findings are also suggestive of FE.

It has been suggested that a basic level of expertise in bedside echocardiography can be achieved by the non-cardiologist in as little as 12 hours of didactic and hands-on teaching. Given this amount of training, the novice ultrasonographer should be able to identify severe left or right ventricular failure, pericardial effusions, regional wall motion abnormalities, gross valvular abnormalities, and volume status by assessing the size and collapsibility of the inferior vena cava (32-37). Potentially, based on this case, the list could include FE with FES in the correct clinical context, pending further clinical validation.

In conclusion, this is the first reported case of bedside ultrasonography assisting in the diagnosis of FES in the ICU. The case illustrates the diagnostic challenge of FE and FES and also highlights the potential utility of bedside ultrasonography as a diagnostic tool.

References

- Akhtar S. Fat Embolism. Anesthesiology Clinics. 2009;27:533-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gitin TA, Seidel T, Cera PJ, Glidewell OJ, Smith JL. Pulmonary microvascular fat: The significance? Critical Care Medicine. 1993;21(5):673-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza SS, Noheria A, Kesman RL. 21-year-old man with chest pain, respiratory distress, and altered mental status. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(5):e29-e32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capan LM, Miller SM, Patel KP. Fat embolism. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 1993;11:25–54.

- Shine TS, Feinglass NG, Leone BJ, Murray PM. Transesophageal echocardiography for detection of propagating, massive emboli during prosthetic hip fracture surgery. Iowa Orthop J. 2010;30:211-4. [PubMed]

- Heinrich H, Kremer P, Winter H, Wörsdorfer O, Ahnefeld FW. Transesophageal 2-dimensional echocardiography in hip endoprostheses. Anaesthesist. 1985;34(3):118-23. [PubMed]

- Pell AC, Christie J, Keating JF, Sutherland GR. The detection of fat embolism by transoesophageal echocardiography during reamed intramedullary nailing. A study of 24 patients with femoral and tibialfractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1993; 75:921-5. [PubMed]

- Christie J, Robinson CM, Pell AC, McBirnie J, Burnett R. Transcardiac echocardiography during invasive intramedullary procedures. J BoneJoint Surg Br 1995;77:450-5. [PubMed]

- Pazell JA, Peltier LF. Experience with sixty-three patients with fat embolism. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1972;135(1):77–80. [PubMed]

- Gossling HR, Pellegrini VD Jr. Fat embolism syndrome: a review of the pathophysiology and physiological basis of treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;165:68–82. [PubMed]

- Shaikh N, Parchani A, Bhat V, Kattren MA. Fat embolism syndrome: Clinical and imaging considerations: Case report and review of literature. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2008;12(1):32-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butteriss DJ, Mahad D, Soh C, Walls T, Weir D, Birchall D. Reversible cytotoxic cerebral edema incerebral fat embolism. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27(3):620-3. [PubMed]

- Nandi R, Krishna HM, Shetty N. Fat embolism syndrome presenting as sudden loss of consciousness. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2010;26(4):549-50. [Pubmed]

- Adams CB. The retinal manifestations of fat embolism. Injury. 1971;2(3):221-4. [CrossRef]

- Mellor A, Soni N. Fat embolism. Anaesthesia. 2001;56:145-54. [CrossRef]

- Bulger EM, Smith DG, Maier RV, Jurkovich GJ. Fat embolism syndrome. A 10-year review. Arch Surg. 1997;132:435-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller P, Prahlow JA. Autopsy diagnosis of fat emboli syndrome. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2011;32(3):291-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurd AR. Fat embolism: an aid to diagnosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1970;52(4):732-7. [PubMed]

- Gurd AR, Wilson RI. The fat embolism syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1974;56(3):408-16.

- Weisz GM, Rang M, Salter RB. Posttraumatic fat embolism in children: review of the literature and of experience in the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. J Trauma. 1973;13:529-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindeque BG, Schoeman HS, Dommisse GF, Boeyens MC, Vlok AL. Fat embolism and the fat embolism syndrome. A double-blind therapeutic study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1987;69(1):128-31. [PubMed]

- Schonfeld SA, Ploysongsang Y, DiLisio R, Crissman JD, Miller E, Hammerschmidt DE, Jacob HS. Fat embolism prophylaxis with corticosteroids. A prospective study in high-risk patients. Ann Intern Med. 1983;99:438-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pell AC, Hughes D, Keating J, Christie J, Busuttil A, Sutherland GR. Fulminating fat embolism syndrome caused by paradoxical embolism through a patent foramen ovale. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:926-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argenziano M. The incidental finding of a patent foramen ovale during cardiac surgery: should it always be repaired? Anesth Analg. 2007;105:611-2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emson HE. Fat embolism studied in 100 patients dying after injury. J Clin Pathol. 1958;11(1):28-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batra P. The fat embolism syndrome. J Thorac Imaging. 1987;2(3):12–17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer N, Pennington WT, Dewitt D, Schmeling GJ. Isolated cerebral fat emboli syndrome in multiply injured patients: a review of three casesand the literature. J Trauma. 2007;63:1395-1402. [PubMed]

- Nijsten MW, Hamer JP, ten Duis HJ, Posma JL. Fat embolism and patent foramen ovale [letter]. Lancet 1989;1(8649):1271. [CrossRef]

- Aoki N, Soma K, Shindo M, Kurosawa T, Ohwada T. Evaluation of potential fat emboli during placement of intramedullary nails after orthopedic fractures. Chest. 1998;113(1):178-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbot M, Schemitsch EH. Fat embolism syndrome: history, definition, epidemiology. Injury. 2006;37S:S3-S7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy D. The fat embolism syndrome. A review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;261:281-6. [PubMed]

- Vignon P, Mücke F, Bellec F, Marin B, Croce J, Brouqui T, Palobart C, Senges P, Truffy C, Wachmann A, Dugard A, Amiel JB. Basic critical care echocardiography: Validation of a curriculum dedicated to noncardiologist residents. Crit Care Med. Apr 2011;39(4):636-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignon P, Dugard A, Abraham J, Belcour D, Gondran G, Pepino F, Marin B, François B, Gastinne H. Focused training for goal-oriented hand-held echocardiography performed by noncardiologist residents in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(10):1795-99. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manasia AR, Nagaraj HM, Kodali RB, Croft LB, Oropello JM, Kohli-Seth R, Leibowitz AB, DelGiudice R, Hufanda JF, Benjamin E, Goldman ME. Feasibility and potential clinical utility of goal-directed transthoracic echocardiography performed by noncardiologist intensivists using a small hand-carried device (SonoHeart) in critically ill patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2005;19(2):155-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melamed R, Sprenkle MD, Ulstad VK, Herzog CA, Leatherman JW. Assessment of left ventricular function by intensivists using hand-held echocardiography. Chest. Jun 2009;135(6):1416-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignon P, Chastagner C, François B, Martaillé JF, Normand S, Bonnivard M, Gastinne H. Diagnostic ability of hand-held echocardiography in ventilated critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2003;7(5):R84-91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo PH, Beaulieu Y, Doelken P, Feller-Kopman D, Harrod C, Kaplan A, Oropello J, Vieillard-Baron A, Axler O, Lichtenstein D, Maury E, Slama M, Vignon P. American College of Chest Physicians/La Societe de Reanimation de Langue Francaise statement on competence in critical care ultrasonography. Chest. 2009;135(4):1050-60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Reference as: Summerfield DT, Cawcutt K, Van Demark R, Ritter MJ. Fat embolism syndrome: improved diagnosis through the use of bedside echocardiography. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2013;7(4):255-64. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc109-13 PDF