Patricia A. Mayer, MD

David H. Beyda, MD

C. Bree Johnston, MD

Department of Bioethics and Medical Humanism and Medicine, The University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ USA

Abstract

The Addendum initially posted on ADHS has been removed. It appears to have been altered including removal of the authors. To see the original Addendum click here.

Abbreviations

-

ADHS: Arizona Department of Health Services

-

CMO: Chief Medical Officer

-

CSC: Arizona Crisisi Standards of Care Plan, 3rd edition

-

SDMAC: State Disaster Medical Advisory Committee

The Challenge

Potential shortages of ventilators and other scarce resources during COVID-19 compelled creation of plans to allocate resources fairly (1). Without protocols, resources would be allocated on a first come first serve basis, which is inefficient and ethically problematic (1-4). Without a cohesive state plan, public confusion combined with uneven resources could lead to “hospital shopping” with vastly different individual outcomes that would likely benefit patients with greater social or economic advantages and be determined by geography rather than medical criteria.

The Goal

Because the existing Arizona Crisis Standards of Care Plan, 3rd edition (CSC, 2) was deemed too non-specific to apply usefully in the pandemic, representatives from hospitals and hospital systems across the state, including small rural hospitals, competing private hospital systems, and federal agencies (Indian Health Service and the Veteran’s Administration) sought a common triage protocol to addend the CSC. The goal was to create a protocol accepted by all hospitals, health care systems and ADHS.

Background

The pandemic caused severe and previously unknown shortages of personal protective equipment and life-sustaining equipment and therapies (6). Much has been written about the need to allocate scarce resources in a manner that is fair, consistent, and based on sound ethical principles. Multiple states, cities, and health systems have shared their processes and protocols for triage during the pandemic (7,8) However, integration between disparate systems has proved challenging at both the local, state and federal levels. Arizona is the sixth largest state in the country and the fourteenth most populous, with five-sixths of the population concentrated in two main metropolitan areas:Phoenix and Tucson. In addition, Arizona is home to twenty-one Native American tribes/nations. Most of the state is rural, distances from populated areas to health care facilities can be great, and access to health care is unevenly distributed. In Arizona health insurance coverage of the population is 45.1% employer, 5.2% non-group, 21% AHCCCS (Arizona’s Medicaid equivalent), 21.6% Medicare, 1.5% Military, and 11.1% uninsured (9).

Triage ethics differ from “usual” clinical ethics in which the lens is the individual patient and all patients have access to life-sustaining treatments. hen life-sustaining resources are insufficient (e.g., pandemics, war), the concentration of the lens shifts from the individual good to the greater community (10). This shift is not only challenging for health care workers but also for a society that is increasingly divided and distrustful of experts. Therefore, it was clear that any protocol had to be fair, transparent and uniform across the state in order to be and acceptable. This necessitated cooperation between organizations traditional in competition with each other that lacked a solid framework for this kind of emergency cooperation.

Creation and Adoption

In the early months of 2020, New York City and Italy were epicenters of the pandemic, and the world watched as they were overwhelmed with cases causing a shortage of beds and personal protective equipment. In response, Arizona hospitals health systems rapidly their existing triage protocols and the state CSC. Therefore, amid predictions for a major surge in Arizona by summer 2020, Phoenix area hospital chief medical officers (CMOs) created the Triage Collaborative. The first meeting laid a foundation for seamless collaboration since all participants, CMOs or their physician designees, were empowered to make decisions during the meetings without delay . This framework, uniquely possible due to the acute time pressure of the pandemic, enabled broader, more streamlined collaboration than had previously been possible between organizations that were normally in competition.

At the second meeting a week later, with representatives from the entire state ADHS proposed a “Surge Line”. This 24/7 state-run hotline accessible to all Arizona healthcare providers rapid transfers of COVID-19 patients to needed levels of care possible due to its ability to monitor statewide resource availability. All agreed to take part in the Surge Line, and it was rapidly implemented (11) Notably, and critical to success of the Surge Line, participation was mandated and insurers required to cover transfers and COVID-19 treatment at in-network rates by the Governor’s Executive Order 2020-38 in late May (12).

On April 9, the Governor issued Executive Order 2020-27 which called for immunity from civil liability “in the course of providing medical services in support of the State’s public health emergency for COVID-19… (including) triage decisions…based on…reliance of mandatory or voluntary state-approved protocols …” (13). This the necessity of a state-approved protocol. ADHS agreed to consider any protocol presented to them by the medical community.

Driven by that Order, the Collaborative immediately shifted from sharing individual protocols to developing the needed statewide protocol In addition, the Collaborative committed to cooperation agreeing that no facility would have to triage unless the entire state was overwhelmed (14). To create the protocol writing group of eight from seven different systems volunteered to begin work immediately.

The writing goup reviewed the existing CSC and individual system protocols for suitability and agreed a new protocol was required that would be transparent, ethically sound and reflect current best practices. After reviewing protocols from other states and literature on triage ethics, the group agreed on goal: maximize the number of lives saved while treating patients without discrimination.

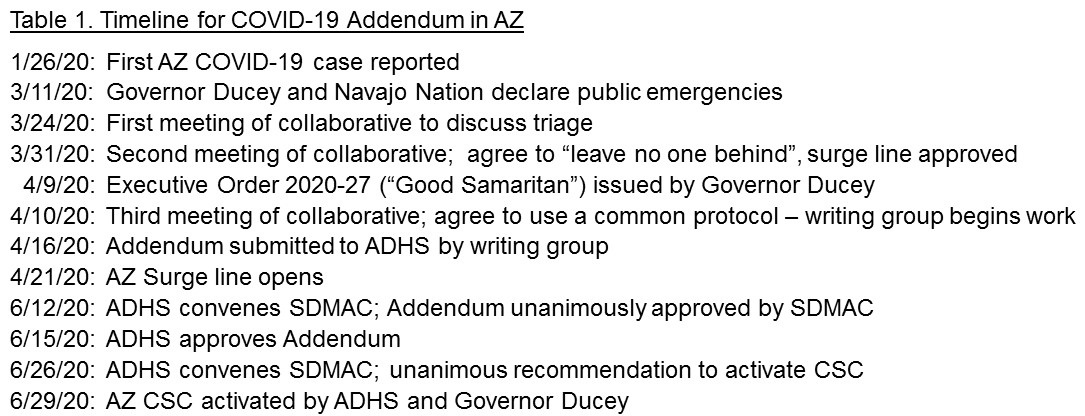

ADHS convened the State Disaster Medical Advisory Committee (SDMAC) in mid-June where the Addendum was discussed and approved. ADHS then accepted and published the final COVID-19 Addendum: Allocation of Scarce Resources for Acute Care Facilities (15). The SDMAC was reconvened again in late June and recommended activation of the CSC, including the Addendum. The formal activation of the CSC by the Governor and ADHS on June 29 was unprecedented and signaled the ability to proceed with triage per the Addendum if needed. Arizona experienced its first major surge shortly thereafter, in July 2020. (for Timeline see Table 1 below).

Ethical Considerations

After a great deal of discussion, the writing group agreed on several key concepts:

-

Goals of care should be assessed as the first step in triage so that patients who do not desire ventilators or ICU beds will not compete for scarce resources that are unwanted (10).

-

The best available acute assessment score (e.g., SOFA, PELOD) should be utilized as an initial triage tool but should not be used alone (6-8).

-

Limited life expectancy should be included as a triage factor.

-

The protocol should avoid categorical exclusions and instead be based on prioritization criteria.

-

Perceived quality of life should not be considered.

-

The value of all lives must be explicitly recognized with triage criteria never used to deny resources when they are not scarce.

-

Criteria is only to prioritize patients when resources are scarce.

-

Criteria must not include any ethically irrelevant discriminatory criteria including race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, sex, disability, age, or gender identity.

-

Patients should be re-assessed and re-prioritized periodically based on their clinical course and continued likelihood of benefit.

-

Where “ties” occur in priority scores, the group must agree on which other factors to consider.

-

An explicit statement rejecting reallocation of personal/home ventilators (or any other durable medical equipment) in order to further protect patients with chronic respiratory conditions or disabilities was essential.

The Process

Bringing together the various health systems was remarkably seamless . However, the group faced a tight timeline to complete the protocol to prepare for a potential emergency.

Although members of the writing group agreed on the primary goal (e.g., maximizing number of lives saved), reaching consensus on other principles (e.g., how to incorporate life expectancy, life cycle, and instrumental concerns) was more challenging. However, over a short but intense time, members were able to reach decisions that all “could live with”.

Previous articles have advocated considering not only the number of lives saved using an acute assessment tool but incorporating other considerations, such as maximizing the number of years of life saved and using life cycle considerations (19,20). While the writing group agreed, members expressed concern about possible unintended consequences with those criteria. First, groups that have faced institutional racism and lifelong health disparities were more likely to have a shorter life expectancy and could face “double jeopardy” in triage protocols, particularly if comorbidities more prevalent in communities of color were used (21-4). Likewise, older patients would often be disadvantaged with these criteria. Group members felt strongly that use of life-years saved should be tempered to address these concerns and so elected to include near term life expectancy and the Life Cycle principle. Other issues included whether and how to prioritize pediatric patients, pregnant women, and single caretakers (25,26).

The group did agree to prioritize healthcare and other frontline workers in case of equal scores, not because of greater estimation of “worth” but because of the instrumental value they serve in the community and as an acknowledgement of their increased risk.

While the writing group did resolve issues in a way all parties “could live with”, members recognized ongoing discussions and updates would be important. For instance, after our Addendum was created, a strong case was made that triage policies should also promote population health outcomes and mitigate health inequalities (23). We echo the need to grapple with how best to address these equity and justice concerns. And although no protocol can perfectly reconcile all tensions we hope the Addendum reflects our sincere attempt to balance competing considerations fairly, ethically, and in a way that could be widely implemented if needed.

The Team

Arizona demonstrated a collaboration between all its hospitals and health systems with a subgroup of physician-ethicist representatives writing, employees at ADHS formatting and supporting the work, the SDMAC endorsing it, and the ADHS then accepting and publishing the Addendum with the agreement of the Governor’s’ office.

The Follow-up

Arizona survived both the July 2020 and the January 2021 surges without resorting to triage and all hospitals and health systems continue to cooperate. The state Surge Line continues to function and as of Feb 1 had transferred over 3700 patients across the state. We remain acutely aware of the ongoing challenges of public perception, news reports, and social media, particularly in a society as divided as the U.S. is today. Already, the Addendum has been mis-characterized on social media as allowing health care providers to refuse scarce resources to older people and those with disabilities. We particularly hope that further conversations occurring outside the acute impending emergency will allow time for public engagement, which will provide valuable input and may mitigate inaccurate perceptions of the criteria used. Meantime, we believe our statewide transparent approach, with the support of ADHS, provided a novel approach and contributed to the state avoiding triage during the worst of our surges.

Conclusion

We believe the cooperation of in developing a shared triage Addendum represents a unique contribution and may provide a model for other localities facing public health emergencies requiring rapid decisive action.

References

-

ADHS. COVID-19 Addendum: Allocation of Scarce Resources in Acute Care Facilities, Recommended for Approval by State Disaster Medical Advisory Committee (SDMAC) 6/12/2020. Available at https://www.azdhs.gov/documents/preparedness/epidemiology-disease-control/infectious-disease-epidemiology/novel-coronavirus/sdmac/covid-19-addendum.pdf.

-

Ventilator allocation guidelines. Albany: New York State Task Force on Life and the Law, New York State Department of Health, November 2015 , available at https://www.health.ny.gov/regulations/task_force/reports_publications/#allocation

-

Ferraresi M. A coronavirus cautionary tale from Italy: don’t do what we did. Boston Globe. March 13, 2020. Available at https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/03/13/opinion/coronavirus-cautionary-tale-italy-dont-do-what-we-did/

-

Sprung CL, Danis M, Iapichino G, et al. Triage of intensive care patients: identifying agreement and controversy. Intensive Care Med. 2013 Nov;39(11):1916-24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

ADHS. Arizona Crisis Standard of Care Plan, 3rd ED. 2020; Available at: https://www.azdhs.gov/documents/preparedness/emergency-preparedness/response-plans/azcsc-plan.pdf

-

Ranney ML, Griffeth V, Jha AK. Critical Supply Shortages - The Need for Ventilators and Personal Protective Equipment during the Covid-19 Pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 30;382(18):e41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Berger JT. Imagining the unthinkable, illuminating the present. J Clin Ethics. 2011 Spring;22(1):17-9. [PubMed]

-

White DB, Lo B. A Framework for Rationing Ventilators and Critical Care Beds During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA. 2020 May 12;323(18):1773-1774. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

KFF Health Policy Analysis, State Health Facts, accessed March 15, 2020 at https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-population/?currentTimeframe=0&selectedRows=%7B%22states%22:%7B%22arizona%22:%7B%7D%7D%7D&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

-

Berger JT. Imagining the unthinkable, illuminating the present. J Clin Ethics, 2011. 22(1): 17-9.

-

Villarroel L, Christ, CM, Smith L et al. Collaboration on the Arizona Surge Line: How Covid-19 Became the Impetus for Public, Private, and Federal Hospitals to Function as One System. NEJM Catalyst, Jan 21, 2021, available at https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0595

-

Office of Governor Doug Ducey. Executive Order : 2020-27: The “Good Samaritan” Order Protecting Frontline Healthcare Workers Responding to the COVID-19 Outbreak”. AZ Governor. Published April 9, 2020.

-

Feldman SL, Mayer PA. Arizona Health Care Systems’ Coordinated Response to COVID-19-“In It Together”. JAMA Health Forum. Published online August 24, 2020. [CrossRef]

-

ADHS. COVID-19 Addendum: Allocation of Scarce Resources in Acute Care Facilities, Recommended for Approval by State Disaster Medical Advisory Committee (SDMAC) 6/12/2020. Available at https://www.azdhs.gov/documents/preparedness/epidemiology-disease-control/infectious-disease-epidemiology/novel-coronavirus/sdmac/covid-19-addendum.pdf

-

Lambden S, Laterre PF, Levy MM, Francois B. The SOFA score-development, utility and challenges of accurate assessment in clinical trials. Crit Care. 2019 Nov 27;23(1):374. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Leteurtre S, Duhamel A, Salleron J, Grandbastien B, Lacroix J, Leclerc F; Groupe Francophone de Réanimation et d’Urgences Pédiatriques (GFRUP). PELOD-2: an update of the PEdiatric logistic organ dysfunction score. Crit Care Med. 2013 Jul;41(7):1761-73. [CrossRef] [PubMed].

-

Straney L, Clements A, Parslow RC, Pearson G, Shann F, Alexander J, Slater A; ANZICS Paediatric Study Group and the Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network. Paediatric index of mortality 3: an updated model for predicting mortality in pediatric intensive care*. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013 Sep;14(7):673-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

White DB, Lo B. A Framework for Rationing Ventilators and Critical Care Beds During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA. 2020 May 12;323(18):1773-1774. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, Thome B, Parker M, Glickman A, Zhang C, Boyle C, Smith M, Phillips JP. Fair Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources in the Time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 May 21;382(21):2049-2055. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Cleveland Manchanda E, Couillard C, Sivashanker K. Inequity in Crisis Standards of Care. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jul 23;383(4):e16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Price-Haywood EG, Burton J, Fort D, Seoane L. Hospitalization and Mortality among Black Patients and White Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jun 25;382(26):2534-2543. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

White DB, Lo B. Mitigating Inequities and Saving Lives with ICU Triage during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Feb 1;203(3):287-295. [CrossRef] [PubMed].

-

Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA, 2020. 323(19): 1891-1892. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Antommaria AH, Powell T, Miller JE, Christian MD; Task Force for Pediatric Emergency Mass Critical Care. Ethical issues in pediatric emergency mass critical care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011 Nov;12(6 Suppl):S163-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Beyda DH. Limited Intensive Care Resources: Fair is What Fair Is Current Concepts in Pediatric Critical Care by the Society of Critical Care Medicine (2015 Edition): 55-59.

-

White DB, Lo B. Mitigating Inequities and Saving Lives with ICU Triage during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2021. 203(3): 287-295.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge ADHS as well as all of their collaborators from the Arizona hospitals and health systems including Abrazo Healthcare and Carondelet Healthcare Phoenix, Tucson & Nogales; Banner Health System; Canyon Vista Medical Center; CommonSpirit Arizona Division Dignity Health; Havasu Regional Medical Center; Honor Health; Indian Health Service; Kingman Regional Medical Center; Northern Arizona HealthCare; Phoenix Children’s Hospital; Summit Healthcare; Tucson Regional Medical Center; University of Arizona College of Medicine; Veteran’s Administration; Valleywise Health; Yavapai Regional Medical Center; Yuma Regional Medical Center.

Cite as: Mayer PA, Beyda DH, Johnston CB. Arizona Hospitals and Health Systems’ Statewide Collaboration Producing a Triage Protocol During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2021;22(6):119-26. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc014-21 PDF