Intubation is one of, and perhaps the, highest risk procedures a critically ill patient can require, and the practice has largely been extrapolated from knowledge gained from airway management in the operating room (OR). Trouble arises when one encounters challenges with placing the tube or performing mask ventilation, termed the ‘difficult airway’. The difficult airway in the OR is relatively rare yet can be catastrophic when it is encountered unexpectedly. As a result, significant resources are devoted to developing task forces, guidelines, new devices and airway adjuncts to help manage the difficult airway and prevent avoidable complications. Outside of the OR, the difficult airway is encountered more frequently and with potentially devastating consequences. Reflexively, it is easy to blame the increased incidence on the skill of those managing airways as airway management has historically been viewed as a laryngoscopy problem--difficulty for us is the source of risk for the patient. Many facilities relegate airway management to an on-call anesthesiologist, leading to a significant variability in training and skill in airway management; and physicians skilled in life support but cannot safely put their patients on life support. Newer devices have led to a significant reduction in the difficulty with laryngoscopy, and it is becoming increasing clear to us that the terminology related to airway management outside of the OR should be reconsidered. Airway management outside of the OR commonly starts with the difficult airway because of the severely altered physiology, thus the importance of first-attempt success. Our current definition of the difficult airway lacks complete appreciation of the risks in these patients by focusing on the difficulty with laryngoscopy for the operator. For airway management of critically ill patients outside of the OR to positively impact patient outcomes, we must broaden our understanding of the risks associated with intubation.

There is no doubt that the difficulty one experiences in performing mask ventilation, laryngoscopy or tracheal intubation puts the patient at risk of untoward complications. However, limiting the focus to this traditional definition neglects the danger to the patient, which can occur in the absence of any technical difficulties. There is a strong association in the published literature between the number of intubation attempts and procedural complications (1-3), however there is also a significant risk of complications despite successful first-attempt tracheal intubation (i.e., no difficulty) (3). Thus, skillfully performing laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation that succeeds easily on the first attempt in a patient with physiologic derangements presents significant danger with airway management. This derangement may relate to a host of physiologic or pathologic issues and the resulting danger to the patient often relates to the consequences of hypoxemia or hypotension. To reduce the danger to the patient, careful attention is required to prepare the patient for induction, laryngoscopy and transition to positive pressure ventilation with emphasis on preoxygenation, maintenance of oxygenation and hemodynamic optimization.

Patients may face danger in any of the three phases of airway management: preparation and planning, implementation of the plan, or post-intubation management. Each phase presents both patient and contextual factors that accumulates and potentially compounds danger. Incomplete preparation, prolonged attempts at tracheal tube placement, disturbed physiology, an unskilled operator in a familiar environment or a skilled operator in an unfamiliar environment all contribute to different phenotypes of complications. All can lead to different phenotypes of complications. Contextual factors include issues such as provider skill, access to equipment and help, various biases and conditions that in part are defined as human factors and are well-known to influence patient outcomes. To help mitigate technical difficulty experienced by the clinician and danger to the patient, special attention must be paid to each phase of airway management.

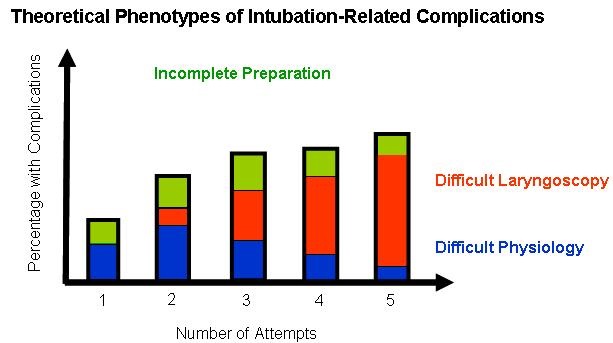

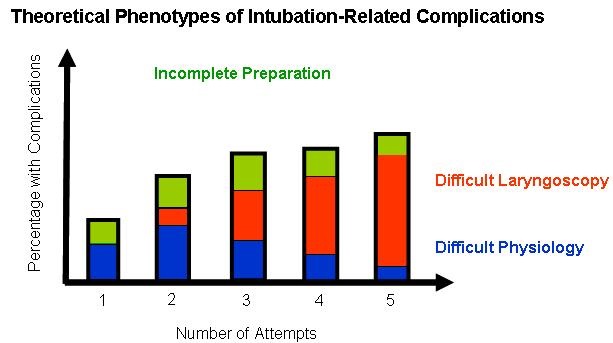

There are three phenotypes of complications that can arise from tracheal intubation. While the incidence of complications increases with successive attempts, the etiology and opportunity to attenuate those complications differs (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Studies outside of the OR show increased complications with successive attempts, with 10-20% for first attempt, 40-60% for second attempt, etc. However, different phenotypes of complications likely contribute differently at each point during airway management and thus provide various clinical and research targets. Incomplete or inadequate preparation or planning results in avoidable intubation-related complications because of early depletion of oxygen reserve, leading to aborted attempts or adverse events earlier than expected (Green bars). Complications that occur due to difficulty with laryngoscopy, tube placement, or mask ventilation despite pre-intubation optimization and preparation increase with successive attempts (Red bars). This is the traditional “difficult airway.” Complications that occur because of altered physiology likely contribute to the majority of complications with 1 or 2 attempts. These patients are so physiologically disturbed (e.g., hypoxemic respiratory failure, RV failure, tamponade), that they are intolerant of any attempt, any apnea, or the transition to positive pressure ventilation. These are the patients that when they degenerate into cardiac arrest despite first attempt success, we tell ourselves that they were just really sick and there’s nothing we could have done.

Complications can arise from inadequate preparation such as preoxygenation, improper positioning or an incomplete plan. Other complications arise from true difficulty with laryngoscopy, tube placement, or mask ventilation despite adequate preparation. With both of these types of complications, repeated attempts can lead to airway injury and edema that can precipitate a can’t-intubate can’t oxygenate scenario, but also the risk is from an association with the depletion of oxygen reserve, hemodynamic consequences of hypoventilation, or aspiration of gastric contents leading to critical hypoxemia. It is this latter association that should be eliminated with an increased focus on danger. Some patients have physiologic challenges that increase the risk of complications with any attempt (i.e. the “physiologically” difficult airway). These disturbances can be so severe that despite optimal preparation, risk cannot be completely obviated. By better understanding the danger presented by these three phenotypes, there is potential to clinically and scientifically approach airway management in critically ill patients that we have not considered historically. To date, we have typically focused efforts on preventing complications related to difficult laryngoscopy, yet the most significant danger likely comes from incomplete preparation and unfriendly physiology.

Continuing to use the ‘difficult airway’ nomenclature in the critically ill patient risks confusion and undue variability without addressing the overall danger. For example, does anticipating difficulty and altering the plan, which then results in no difficulty being encountered during the intubation qualify as a difficult airway? Should one write a note in the chart, register the patient with a database, and send the patient a letter notifying them of the difficult airway they were predicted to have, but yet did not have? This presents a Schrödinger’s cat paradox in that the airway is both difficult and not difficult at the same time. From a research perspective, the term ‘difficult airway’ can be fraught with ambiguity or error. Studies comparing devices, techniques, or methods often focus either on the anticipated difficult airway, which is poorly predicted, deliberately exclude difficult airway patients, or isolate one aspect while ignoring the others (e.g. apneic oxygenation while ignoring preoxygenation) (4-11). Conversely, focusing on laryngoscopy-related complications ignores significant danger in airway management from incomplete preparation and difficult physiology-related complications, especially considering most patients are intubated in the first two attempts. We should refocus our energies on mitigating the danger by optimizing the pre- and peri-intubation process. Research should focus on how to best reduce complications associated with multiple attempts and disturbed physiology, and eliminate complications related to poor preparation altogether. These efforts will elevate our expertise in placing patients on life support to the level our patients deserve.

Jarrod M Mosier, MD1,2,; George Kovacs, MD3; J. Adam Law, MD4; John C Sakles, MD1

1Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Arizona. 1609 N. Warren Ave, Tucson, AZ 85724

2Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care, and Sleep. Department of Medicine, University of Arizona. 1501 N Campbell Ave, Tucson, AZ 85721

3 Departments of Emergency Medicine, Anaesthesia, Medical Neuroscience, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS B3H 3A7

4 Departments of Anesthesiology and Emergency Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS B3H 3A7

References

- Sakles JC, Chiu S, Mosier J, Walker C, Stolz U. The importance of first pass success when performing orotracheal intubation in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(1):71-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mort TC. Emergency tracheal intubation: complications associated with repeated laryngoscopic attempts. Anesth Analg. 2004;99(2):607-11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hypes C, Sakles J, Joshi R, Greenberg J, Natt B, Malo J, Bloom J, Chopra H, Mosier J. Failure to achieve first attempt success at intubation using video laryngoscopy is associated with increased complications. Intern Emerg Med. 2017 Dec;12(8):1235-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griesdale DE, Chau A, Isac G, Ayas N, Foster D, Irwin C, Choi P, Canadian Critical Care Trials G: Video-laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy in critically ill patients: a pilot randomized trial. Can J Anaesth. 2012;59(11):1032-1039. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverberg MJ, Li N, Acquah SO, Kory PD. Comparison of video laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy during urgent endotracheal intubation: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2015 Mar;43(3):636-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driver BE, Prekker ME, Moore JC, Schick AL, Reardon RF, Miner JR. Direct Versus Video Laryngoscopy Using the C-MAC for Tracheal Intubation in the Emergency Department, a Randomized Controlled Trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2016, 23(4):433-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janz DR, Semler MW, Lentz RJ, et al. Randomized Trial of Video Laryngoscopy for Endotracheal Intubation of Critically Ill Adults. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(11):1980-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janz DR, Semler MW, Joffe AM, et al. A multicenter randomized trial of a checklist for endotracheal intubation of critically ill adults. Chest. 2017 Sep 14. pii: S0012-3692(17)32685-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semler MW, Janz DR, Russell DW, Casey JD, Lentz RJ, Zouk AN, deBoisblanc BP, Santanilla JI, Khan YA, Joffe AM et al. A multicenter, randomized trial of ramped position vs sniffing position during endotracheal intubation of critically ill adults. Chest. 2017;152(4):712-2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semler MW, Janz DR, Lentz RJ, et al. Randomized trial of apneic oxygenation during endotracheal intubation of the critically ill. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016 Feb 1;193(3):273-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lascarrou JB, Boisrame-Helms J, Bailly A, et al. Video Laryngoscopy vs direct laryngoscopy on successful first-pass orotracheal intubation among ICU patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(5):483-93. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Mosier JM, Kovacs G, Law JA, Sakles JC. The dangerous airway: reframing airway management in the critically ill. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2018;16(2):99-102. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc004-18 PDF

Saturday, March 31, 2018 at 8:00AM

Saturday, March 31, 2018 at 8:00AM