Richard A. Robbins, MD*

Thomas D. Kummet, MD**

*Phoenix Pulmonary and Critical Care Research and Education Foundation

Gilbert, AZ USA

**Sequim, WA USA

Abstract

Operative removal of non-small cell lung cancer remains the mainstay of therapy. When this is not possible, cytotoxic chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy can be given but are marginally effective in prolonging overall survival. However, with a better understanding of the pathobiology of the lung cancer cells, new targeted therapies have been developed which may produce dramatic responses in selected patients. This brief review will emphasize these newer therapies in this rapidly evolving field.

Introduction

Lung cancer is extremely common and remains by far the most frequent cause of cancer-related death with approximately 154,050 deaths estimated to occur during 2018 (1). Although lung cancer deaths have declined in men, the deaths have risen in women and now account for nearly half of all women’s cancer deaths (1). Unfortunately, the vast majority are diagnosed with advanced, unresectable disease that remains incurable (1). Overall the five-year survival rate is <1% for advanced (stage IVB) disease, while the five-year survival rate for all stages is approximately 15 % (1).

Data linking cigarette smoking to human lung cancer is incontrovertible (2). The risk increases with both the amount of smoking and the duration of smoking (2). Passive or second-hand smoke is also associated with an increase in the risk of lung cancer, although this increase is far lower than that observed with active smoking (2). Smoking cessation clearly decreases the risk of lung cancer (2).

Primary lung cancers can be divided into two main types based on their histology, small cell lung cancer and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (3). NSCLC constitute about 85% of lung cancers with the rest consisting of small cell and some rarer cancers (3). A basic understanding of the pathobiology of NSCLC has shown that the tumor cells depend on the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis), transfer of a phosphate group from ATP to tyrosine on proteins (tyrosine kinase), and regulation of programmed death ligands (checkpoint proteins) (4). Targeted therapy against these pathobiologic processes have shown dramatic effects in some NSCLC patients (4).

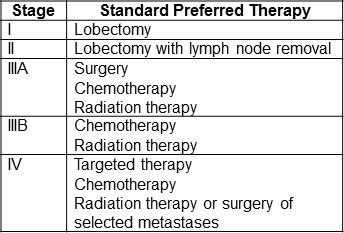

NSCLC is divided into 4 stages designated by roman numerals (5). The stages are based on the size of the tumor; whether it has metastasized locally or distally; and use the TNM classification where T designates tumor size; N regional lymph node metastasis; and M distant metastasis. Stages I and II are limited to the chest but stage III has metastasized to the pleura and/or regional lung lymph nodes. Stage IIIA means the cancer has metastasized to lymph nodes that are on the same side of the chest as the cancer (ipsilateral) while stage IIIB signifies metastasis to lymph nodes on the opposite side of the chest (contralateral). Stage IV denotes there are distant metastasis outside the chest. The above is admittedly an oversimplification and there are subtle nuances that define the stages which can be found at the National Cancer Institute website (5).

An overall summary of standard preferred by the National Cancer Institute for NSCLC by stage is shown in Table 1 (6).

Table 1. Standard preferred therapy for NSCLC by stage (6).

Surgery

Operative removal of the lung cancer is the cornerstone of management for patients with early-stage (stages I–II) NSCLC and selected patients with stage IIIA disease (7). Lobectomy is the operation of choice for localized NSCLC based on a randomized trial of lobectomy versus more limited resection (8). Operative intervention should be offered to all patients with stage I and II NSCLC who clinically are medically fit for surgical resection. However, patients may be unable to undergo a lobectomy for a variety of reasons such as: 1. severely compromised pulmonary function; 2. multisystem disease making lobectomy excessively hazardous; 3. advanced age; or 4. refusal of the operation. Some patients who cannot tolerate a full lobectomy but may be able to tolerate a more limited sublobar operation (6). For patients in whom complete tumor resection cannot be achieved with lobectomy, sleeve lobectomy is recommended over pneumonectomy because it preserves pulmonary function (6). In addition, the question of whether video-assisted thorascopic surgery (VATS) is equivalent to thoracotomy for patients with lung cancer comes up often, particularly in patients that are less than ideal surgical candidates. In a series of 741 patients with stage IA NSCLC, 5-year survival was similar but VATS was associated with fewer complications and a shorter length of hospital stay (9). Therefore, VATS is an optional surgical approach particularly in poorer risk patients.

Radiotherapy

Although lobectomy is the treatment of choice for NSCLC patients with early-stage disease, some are unable to undergo an operation due to reasons listed above. For those patients, radiotherapy can be administered with curative intent, albeit with lower overall survival rates when compared to surgery (10,11).

The radiation oncology community is excited about the potential of stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) (12,13). SBRT is a type of external radiation therapy that uses special equipment to position a patient and precisely deliver radiation to tumors in the body (except the brain). Although there is no data yet, trials are ongoing comparing SBRT with surgery in early stage NSCLC.

Adjuvant Therapy

Adjuvant chemotherapy. Adjuvant chemotherapy is chemotherapy that is given in addition to either surgical and/or radiation therapy. Data from recent randomized adjuvant clinical trials and a meta-analysis support the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in NSCLC (14). A 5.4% five-year survival benefit was observed in a meta-analysis of five randomized trials compared to observation. Not surprisingly, the survival benefit varied according to stage but the benefit was most pronounced for patients with stage II and IIIA disease. Survival benefit in patients with stage IB disease did not reach statistical significance. Importantly, patients with stage IA disease appeared to do worse with adjuvant chemotherapy, and therefore, is not currently recommended.

Adjuvant radiotherapy. The PORT meta-analysis of 2,128 patients demonstrated that the use of post-operative radiotherapy was associated with a detrimental effect on survival (15,16). The decrease in survival was more pronounced for patients with lower nodal status. The PORT meta-analysis has been criticized for its long enrolment period and use of different types of machines, techniques and radiation doses. Despite these criticisms, three randomized phase III trials support the PORT meta-analysis’ conclusion that the use of post-operative radiotherapy provides no survival benefit (17-19). For patients with N2-positive disease, however, a retrospective analysis demonstrated higher survival for those patients who had received post-operative radiotherapy (20). On the basis of the above studies, most do not recommend routine post-operative radiotherapy with the possible exception of those with N2 disease.

Locally Advanced Disease

About a third of patients with NSCLC present with disease that remains localized to the thorax but may be too extensive for surgical treatment (stage III) (21). Concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy is considered the standard therapy for this situation but results in only a modest, although statistically significant, survival benefit compared with sequential administration (21). However, significant toxicity results from this approach and so it is usually offered only to those with good performance status.

Surgery after chemotherapy in patients with N2 disease was tested in two randomized trials. A European trial used three cycles of cisplatin-based chemotherapy, then randomized the patients to surgery or sequential thoracic radiotherapy (22). There was no significant difference in overall survival or progression-free survival. An American trial used a slightly different protocol (23). Patients with N2 disease were given two cycles with concurrent radiotherapy and then randomized to further radiation or surgery. This trial showed a better progression free survival with surgery but no difference in overall survival.

Metastatic Disease

About 40% of patients with NSCLC present with advanced stage IV disease. Until recently, cytotoxic chemotherapy was the cornerstone of treatment for stage IV disease but is now recommended as first line therapy alone only for patients with low or no expression of markers for targeted therapy (24). Unfortunately, in stage IV NSCLC standard cytotoxic chemotherapy alone is minimally effective. A meta-analysis that included 16 randomized trials with 2,714 patients demonstrated that cytotoxic chemotherapy offers an overall survival advantage of only 9% at 12 months compared with supportive care (25). Two-drug chemotherapy (doublets) appears to be superior to either a single agent or three-drug combinations (26). Cisplatin-based doublets are associated with a marginal one-year survival benefit compared with platinum-free regimens (27). Platinum-free regimens can be given as an alternative especially in patients who cannot tolerate platinum-based treatment (24). Although gemcitabine, vinorelbine, paclitaxel or pemetrexed are often added to either cisplatin or carboplatin, the choice of the second drug does not appear to matter in increasing survival (28).

Targeted Therapies

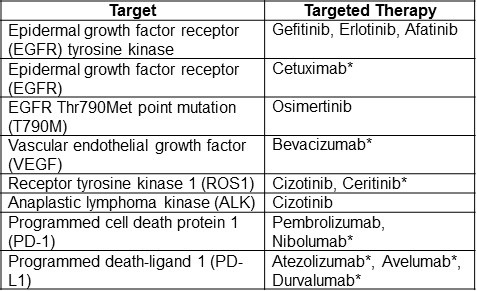

Starting in the early 2000s, NSCLC subtypes have evolved from being histologically described to molecularly defined. The use of targeted therapies in lung cancer based on molecular markers is a very rapidly changing field. At the time this article was being written (February 2018) the information was current but recommended therapies are likely to change with development of new therapies and research. It is important to point out that despite these advances, there remains no cure for stable IV NSCLC. Table 2 represents a summary of targets and targeted therapy along with the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommendations for stage IV NSCLC as of February 2018 (24).

Table 2. Targets and targeted therapies for NSCLC (24).

*Currently not recommended for clinical use by ASCO.

The need for adequate tissue to perform molecular studies creates challenges for pulmonologists doing bronchoscopic procedures. Whereas it was previously adequate to obtain diagnostic material. However, it is now important to obtain adequate tissue to perform additional molecular testing to allow determination of whether targeted therapies are appropriate. Sometimes tissue is inadequate which might necessitate a second procedure if clinically warranted.

Vascular Growth Factors

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR). The EGFR pathway represents the pioneer of personalized medicine in lung cancer. EGFR is a transmembrane receptor that is highly expressed by some NSCLCs. Binding of ligands (epidermal growth factor, tumor growth factor-alpha, betacellulin, epiregulin or amphiregullin) to the extracellular EGFR domain results in autophosphorylation through tyrosine kinase activity (29). This initiates an intracellular signal transduction cascade that affects cell proliferation, motility and survival (29). Inhibition of ligand and EGFR binding or the activation of tyrosine kinases inhibit the downstream pathways resulting in inhibition of cancer cell growth (29).

Initial studies showed that most patients with NSCLC had no response to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), gefitinib, which targets phosphorylation of EGFR (30). However, about 10 percent of patients had a rapid and often dramatic clinical response (30). An explanation for these results occurred with the identification of mutations of the tyrosine kinase coding domain (exons 18–21) of the EGFR gene. Subsequent research linked these mutations to the clinical response to gefitinib (31,32). Although about 10% of Caucasian NSCLC have these mutations, the mutations were observed more commonly in Asian patients, particularly non-smoking women (33). There is now overwhelming and consistent evidence from multiple trials that all the approved EGFR-TKIs (gefitinib, erlotinib, or afatinib) have greater activity than platinum-based chemotherapy as the first-line treatment of patients with advanced NSCLC with activating EGFR mutations (24). These agents have more favorable toxicity profiles than platinum-based chemotherapy and have demonstrated improvements in quality of life. The choice of which EGFR-TKI to recommend to patients should be based on the availability and toxicity of the individual therapy. Randomized clinical trials are ongoing comparing EGFR-TKIs. The results of these trials may help refine this in the future.

Despite high tumor response rates with first-line EGFR-TKIs, NSCLC progresses in a majority of patients after 9 to 13 months of treatment. At the time of progression, approximately 60% of patients (regardless of race or ethnic background) are found to have a Thr790Met point mutation (T790M) in the gene encoding EGFR (34). The presence of the T790M variant reduces binding of first-generation EGFR-TKIs to the leading to disease progression (34). Osimertinib is an irreversible EGFR-TKI that can bind to EGFR despite the T790M resistance mutations and has recently become clinically available (35). Currently it is recommended for T790M mutations that occur after the first-line EGFR-TKIs have failed (24).

Cetuximab is a monoclonal antibody directed against EGFR itself. In the past, addition of cetuximab to cisplatin doublet chemotherapy in EGFR positive tumors was usual. However, cetuximab has recently been shown to shorten progression free survival with some adverse effects and is no longer recommended (24).

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels, is a fundamental process for the development of solid tumors and the growth of secondary metastatic lesions. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) acts to promote normal and tumor angiogenesis. Bevacizumab, a recombinant, humanized, monoclonal antibody against VEGF, was previously recommended as first-line therapy in stage IV NSCLC patients without a contraindication. However, the most recent ASCO guidelines finds insufficient evidence to recommend bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line treatment (24).

Other Kinase Inhibitors. Receptor tyrosine kinase 1 (ROS1) and the structurally similar anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) are enzymes that are critical regulators of normal cellular activity. In NSCLC rearrangements of these genes can cause them to act as oncogenes, or genes that transform normal cells into cancer cells. Rearrangements in the ROS1 or ALK genes are found in a small percentage of patients with NSCLC. Crizotinib is a molecule that blocks both the ROS1 and ALK proteins. Crizotinib reduced tumor size in ALK+ or ROS1+ positive patients although the most recent ASCO guidelines consider the evidence only moderate with ALK+ and weak with ROS1+ patients (24,36-8).

Checkpoint Inhibitors. An important part of the immune system is its ability to tell the difference between normal cells and those that are “foreign”. To do this, it uses “checkpoints”, molecules on certain immune cells that need to be activated (or inactivated) to start an immune response (39). NSCLC can use these checkpoints to avoid being attacked by the immune system. Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) is a checkpoint protein on T cells. It normally acts as an “off switch” when it attaches to programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), a protein on some normal (and cancer) cells. Some NSCLCs have large amounts of PD-L1, which helps them evade immune attack. Monoclonal antibodies that target either PD-1 or PD-L1 can block this binding and boost the immune response against NSCLC cells. In patients with NSCLC with >50% of their tumor cells PD-1+ (tumor proportion score >50%), pembrolizumab, a monoclonal antibody against PD-1, significantly prolonged progression-free and overall survival compared to platinum-based chemotherapy (40). Based on this trial, pembrolizumab is now recommended by ASCO for patients with a tumor proportion score >50% for PD-1 (23). A number of other PD-1 (e.g., nibolumab) and PD-L1 inhibitors (e.g., atezolizumab, avelumab, durvalumab) exist but ASCO recommends only pembrolizumab at this time (39,40). As more of these checkpoint inhibitors are developed and tested this will likely change.

Second and Third-Line NSCLC Therapy

Second and third-line therapy for NSCLC is beyond the scope of this brief review. It is a rapidly evolving field which should include close collaboration between the pulmonologist, oncologist and other members of the patient’s NSCLC treatment team.

After an initial response, lung cancers can become resistant to therapy. One example mentioned above is the development of the T790M mutation in EGFR+ NSCLC. In selected instances rebiopsy of the primary tumor or metastases can direct a new, effective therapy. Obviously, it is not possible to rebiopsy every NSCLC patient after failure of the initial therapy. However, other techniques are being investigated. One is liquid biopsy where blood is drawn and subjected to molecular techniques to determine a possible cause for tumor resistance. Multiple liquid biopsy molecular methods are presently being examined to determine their efficacy as surrogates to the tumor tissue biopsy (41).

Future Directions

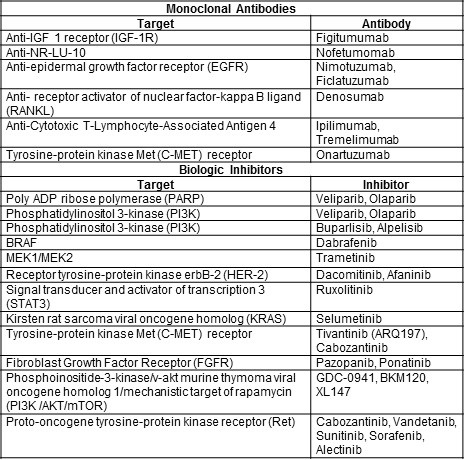

The combination of a variety of existing therapies for NSCLC is being evaluated. These will likely yield revised recommendations for therapy. In addition, a variety of therapies, both existing for other cancers, or newer therapies in development are being tested. These include both monoclonal antibodies and biologic inhibitors (Table 3).

Table 3. Potential new targeted therapies for NSCLC (42,43).

The numbers of pathways and drugs being tested is very impressive and the clinical responses can be dramatic in some patients. One might be tempted to conclude that these therapies might result in a “cure” for NSCLC. However, most of these mutations occur in a small minority of NSCLCs. Furthermore, even if initially successful, resistance to targeted therapies may quickly develop limiting their clinical usefulness in NSCLC.

Targeted therapies may also have potential as adjuvant therapies. In support of this concept, a recent phase 3 study compared durvalumab as consolidation therapy with placebo in patients with stage III NSCLC who did not have disease progression after two or more cycles of platinum-based chemoradiotherapy (44). The progression-free survival was 16.8 months with durvalumab versus 5.6 months with placebo (p<0.001). It seems likely that more trials using targeted therapy earlier in cancer therapy will be done.

References

- American Cancer Society. Key statistics for lung cancer. 2016. Available at: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/non-small-cell-lung-cancer/about/key-statistics.html (accessed 2/17/18).

- The Health Consequences of Smoking-50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Washington, DC, 2016. Available at: https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/full-report.pdf (accessed 2/17/18).

- American Cancer Society. What Is non-small cell lung cancer? 2016. Available at: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/non-small-cell-lung-cancer/about/what-is-non-small-cell-lung-cancer.html (accessed 2/17/18).

- American Cancer Society. Targeted therapy drugs for non-small cell lung cancer. June 23, 2017. Available at: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/non-small-cell-lung-cancer/treating/targeted-therapies.html (accessed 2/17/18).

- National Cancer Institute. Non-small cell lung cancer treatment (PDQ®)–health professional version: Stage information for NSCLC. February 1, 2018. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/hp/non-small-cell-lung-treatment-pdq#section/_470 (accessed 2/19/18).

- National Cancer Institute. Non-small cell lung cancer treatment (PDQ®)–health professional version: Treatment option overview for NSCLC. February 1, 2018. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/hp/non-small-cell-lung-treatment-pdq#section/_4889 (accessed 2/19/18).

- Howington JA, Blum MG, Chang AC, Balekian AA, Murthy SC. Treatment of stage I and II non-small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013 May;143(5 Suppl):e278S-e313S. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginsberg RJ, Rubinstein LV. Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1 N0 non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Study Group. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;57(3):615-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores RM, Park BJ, Dycoco J, et al. Lobectomy by video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) versus thoracotomy for lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009 Jul;138(1):11-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowell NP, Williams CJ. Radical radiotherapy for stage I/II non-small cell lung cancer in patients not sufficiently fit for or declining surgery (medically inoperable): a systematic review. Thorax. 2001;56(8):628-38. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowell NP, Williams CJ. Radical radiotherapy for stage I/II non-small cell lung cancer in patients not sufficiently fit for or declining surgery (medically inoperable). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(2):CD002935. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu CE, Ferreira PP, de Moraes FY, Neves WF Jr, Gadia R, Carvalho Hde A. Stereotactic body radiotherapy in lung cancer: an update. J Bras Pneumol. 2015 Jul-Aug;41(4):376-87. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandberg DJ, Tong BC, Ackerson BG, Kelsey CR. Surgery versus stereotactic body radiation therapy for stage I non-small cell lung cancer: A comprehensive review. Cancer. 2018 Feb 15;124(4):667-78. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés AA, Urquizu LC, Cubero JH. Adjuvant chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: state-of-the-art. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015 Apr;4(2):191-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PORT Meta-analysis Trialists Group. Postoperative radiotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from nine randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 1998;352(9124):257-63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdett S, Stewart L. Postoperative radiotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer: update of an individual patient data meta-analysis. Lung Cancer. 2005;47(1):81-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer R, Smolle-Juettner FM, Szolar D, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in radically resected non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 1997;112(4):954-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dautzenberg B, Arriagada R, Chammard AB, et al. A controlled study of postoperative radiotherapy for patients with completely resected nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86(2):265-73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng QF, Wang M, Wang LJ, et al. A study of postoperative radiotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47(4):925-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douillard JY, Rosell R, De LM, et al. Adjuvant vinorelbine plus cisplatin versus observation in patients with completely resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (Adjuvant Navelbine International Trialist Association [ANITA]): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(9):719-27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramnath N, Dilling TJ, Harris LJ, et al. Treatment of stage III non-small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013 May;143(5 Suppl):e314S-e340S. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Meerbeeck JP, Kramer GW, Van Schil PE, et al. Randomized controlled trial of resection versus radiotherapy after induction chemotherapy in stage IIIA-N2 non-small-cell lung cancer, J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(6):442-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albain KS, Swann RS, Rusch VW, et al. Radiotherapy plus chemotherapy with or without surgical resection for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 2009;374(9687):379-86. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna N, Johnson D, Temin S, et al. Systemic therapy for stage IV non–small-cell lung cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3484-515. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NSCLC Meta-Analyses Collaborative Group. Chemotherapy in addition to supportive care improves survival in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from 16 randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Oct 1;26(28):4617-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilenbaum RC, Herndon JE, List MA, et al. Single-agent versus combination chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the cancer and leukemia group B (study 9730), J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(1):190-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delbaldo C, Michiels S, Syz N, et al. Benefits of adding a drug to a single-agent or a 2-agent chemotherapy regimen in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292(4):470-84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, et al. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer, N Engl J Med. 2002;346(2):92-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citri A, Yarden Y. EGF-ERBB signalling: towards the systems level. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(7):505-16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kris MG, Natale RB, Herbst RS, et al. Efficacy of gefitinib, an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2149-58. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(21):2129-39. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304(5676):1497-500. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch FR and Bunn PA Jr. EGFR testing in lung cancer is ready for prime time. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(5):432-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non–small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:786-92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok TS, Wu YL, Ahn MJ, et al. Osimertinib or platinum-pemetrexed in EGFR T790M-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:629-40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):2385-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BJ Solomon, T Mok, DW Kim, et al. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer N Engl J Med 2014;371(23):2167-77. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto K, Chih-Hsin Yang J, Kim DW: Phase II study of crizotinib in east Asian patients (pts) with ROS1-positive advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol. 2016; 34:(suppl; abstr 9022).

- American Cancer Society. Immune checkpoint inhibitors to treat cancer. May 1, 2017. Available at: https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/treatment-types/immunotherapy/immune-checkpoint-inhibitors.html (accessed 2/19/18).

- Reck M, Rodrıguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PDL1-positive non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1823-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari J, Yun JW, Kompelli AR, et al. The liquid biopsy in lung cancer. Genes Cancer. 2016 Nov;7(11-12):355-67. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortinovis D, Abbate M, Bidoli P, Capici S, Canova S. Targeted therapies and immunotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Ecancer. 2016;10:648-75. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva AP, Coelho PV, Anazetti M, Simioni PU.Targeted therapies for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer: Monoclonal antibodies and biological inhibitors. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017 Apr 3;13(4):843-53. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al. Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017 Nov 16;377(20):1919-29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Robbins RA, Kummet TD. First-line therapy for non-small cell lung cancer including targeted therapy: A brief review. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2018;16(3):157-67. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc038-18 PDF