Sabeen Yaqub, MD

Michelle S. Harkins, MD

Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine

Department of Internal Medicine.

University on New Mexico

Albuquerque, NM 87131

Emails: sabeenyaqub@gmail.com

MHarkins@salud.unm.edu

None of the authors of the above manuscript has declared any conflict of interest, which may arise from being named as an author on the manuscript.

Reference as: Yaqub S, Harkins MS. A 39 year old female with progressive dyspnea, dry cough and hypoxia: a case report. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2011;3:134-40. (Click here for a PDF version of the manuscript)

Case Presentation

A previously healthy 39 year old female presented with progressive shortness of breath on exertion, dry cough, fatigue, fevers and hypoxia for the last four months. Her symptoms worsened despite being on several courses of antibiotics. Her past medical history is significant for hypertension and diabetes and medications include metoprolol and fosinopril. There is no previous history of cigarette smoking, drugs or alcohol abuse. She denied any weight loss. She was evaluated by a pulmonologist at an outside facility before being transported to our facility. Workup included chest x-ray and CT scan which showed patchy areas of consolidation. A bronchoscopy with bronchial alveolar lavage (BAL) was also performed but she became profoundly hypoxic and was transferred to the ICU intubated.

Physical Exam

An obese female who was intubated and sedated on pressure targeted ventilation with delta P 28, rate 15, FiO2 60% peep 8. Her vitals revealed a Tmax of 38.6 C and blood pressure of 146/85. There were coarse breath sounds bilaterally and mild diffuse crackles in all lung fields. No clubbing or cyanosis was noted. The rest of the exam was unremarkable with a normal abdominal, cardiac and skin exam. There was no adenopathy.

Labs

Complete blood count, electrolytes and liver function tests were normal. HIV testing was negative.

Radiological findings

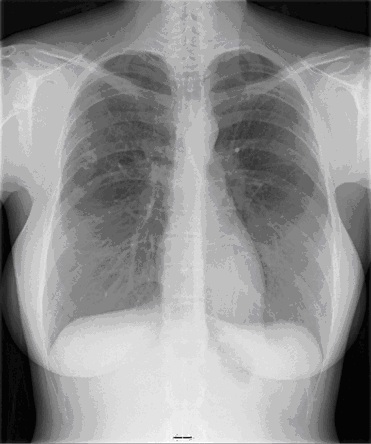

Chest x-ray demonstrated perihilar and bibasilar opacities.

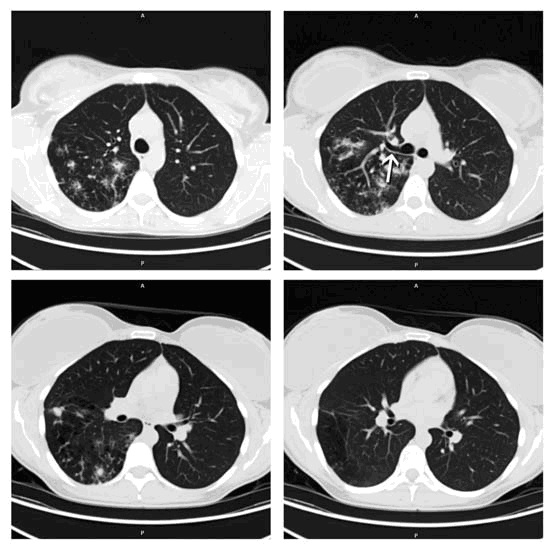

CT scan is shown below in Figure 1.

Figure 1: CT Scan - Diffuse and geographic ground glass opacities accompanied by interlobular septal thickening consistent with the classic “crazy paving” with geographic distribution.

Bronchoscopy

Bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed which revealed an opaque appearing fluid with particulate matter. An open lung biopsy was performed to confirm the suspected diagnosis.

Pathology

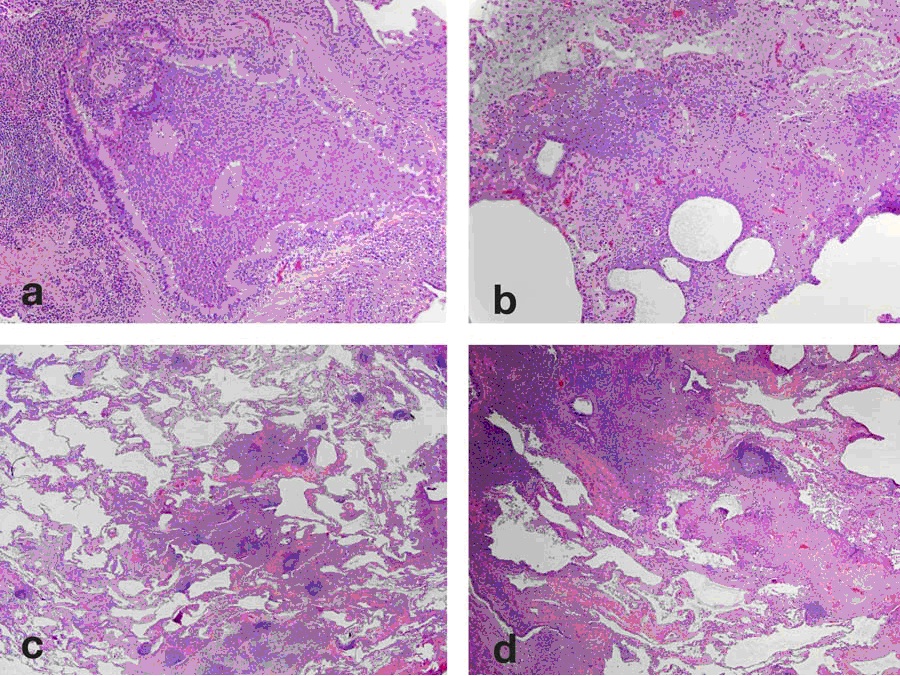

Open Lung Biopsy revealed normal alveolar architecture with eosinophilic staining debris within the alveolar spaces that was Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) + (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Open Lung Biopsy: Numerous alveolar spaces filled with abundant eosinophilic material (A) which is PAS positive (B) and occasional dense globular clumps with intra-alveolar macrophages. The alveolar septae are delicate without evidence of fibrosis.

Diagnosis: Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis (PAP)

Hospital Course

She underwent a partial whole lung lavage of the right lung first and remained intubated post procedure. She underwent a repeat lavage of the right lung four days later and then a whole lung lavage on the left one week later due to bilateral infiltrates and difficulty weaning from the ventilator. Each lavage consisted of 12 liters of warmed saline and there was progressive clearing of the cloudy material obtained by the end of the lavage. BAL cultures were obtained which were positive for Staphlococcus aureus and Klebsiella but were negative for Nocardia, Pneumocystis, and acid fast bacilli. She was treated with antibiotics for 7 days for the bacterial infection. She was then successfully extubated.

Discussion

PAP also known as pulmonary alveolar phospholipoproteinosis is a diffuse lung disease characterized by accumulation of amorphous PAS+ lipoproteinaceous material in the distal airspaces with little or no inflammation and preservation of the underlying lung architecture.1-3

Three forms of PAP are recognized; congenital, secondary and acquired. Congenital form is present in neonates and results from mutations in genes for surfactants or GM-CSF receptors. The acquired form is the most common and GM-CSF antibodies contribute to macrophage dysfunction and impaired processing of surfactant. The secondary form is associated with high level dust exposure (silica, aluminium, titanium), hematologic malignancy and after allogenic bone marrow transplant for myeloid malignancy and infection (Nocardia, viral, Pneumocystis). Macrophages are overwhelmed by accumulation of surfactant rich material and they lose the ability to phagocytize.

Clinical signs and symptoms include dyspnea on exertion, cough, fatigue, weight loss and low grade fevers. Clubbing, cyanosis and crackles on physical exam may be present. Patients with PAP have an increased risk of opportunistic infection with Nocardia, Mycobacteria, fungi and Pneumocystis due to impaired macrophage and neutrophil function. Laboratory abnormalities include polycythemia, hypergammaglobulinemia, and increased LDL. On Chest x-ray bilateral symmetrical alveolar opacities are located centrally in the mid and lower lung zones in a ‘bat wing’ distribution. CT scan reveals heterogenous distribution of ground glass opacification and septal thickening.

The diagnostic work-up should include a history and physical consistent with PAP, a CT scan, fiberoptic bronchoscopy to obtain lavage fluid and transbronchial biopsies and serum assay for Anti-GM-CSF antibodies. To exclude the presence of concurrent infections special stains and cultures for opportunistic infection should be obtained. In one of the largest cohort studies of 248 PAP patients, diagnosis was made by High Resolution CT (HRCT) scan and BAL in 59%; HRCT, BAL and transbronchial biopsy in 34% and VATS biopsy in 7%.4 Characteristic findings on BAL are an opaque or milky appearance due to abundant lipoproteinaceous material, alveolar macrophages that are engorged with PAS positive material, increased SP-A levels and large acellular eosinophilic bodies. On histological specimens, the normal alveolar architecture is preserved although the alveolar septa may be thickened due to type-2 cell hyperplasia. There is little or no inflammatory cell infiltrate. The terminal bronchioles and alveoli are filled with PAS positive lipoproteinaceous material.

The treatment options vary with the severity of disease. In the cohort study, asymptomatic patients were the most likely to have a stable course and only 8% worsened during follow up. 4 Among symptomatic patients the proportion of stable, improved and worsening disease was 45%, 30%, and 25% respectively. Patients with longer duration are likely to have progressive disease.

Asymptomatic patients can be observed with periodic reassessment of symptoms, pulmonary function testing (PFTs) and chest x-rays (CXRs). In patients with mild symptoms (mild hypoxia on exertion, normoxia on rest) supplemental oxygen is appropriate. Patients with moderate to severe disease may elect for whole lung lavage or a trial of experimental treatment with GM-CSF or plasmapheresis. Whole lung lavage under general anesthesia via a double lumen endotracheal tube is recommended for patients who have moderate to severe disease.5-7 Indications for lung lavage include resting PaO2 <65, A-a gradient >40, shunt fraction>10-12% and severe hypoxia or dyspnea on rest and exertion. Clinical course is variable. Thirty-forty percent of patients require one lavage while others require lung lavage at intervals of 6-12 months.

Experimental therapy with GM-CSF has been used. 8-13 In an open trial of 25 patients, GM-CSF was given subcutaneously and 48% experienced symptomatic and radiological improvement. However the proportion of responders to whole lung lavage appears to be the largest.11-12 Given the experimental nature of GM-CSF therapy, lung lavage as primary therapy is recommended. Lung transplant is reserved for patients who deteriorate despite whole lung lavage but recurrence in allograft has been reported.14 Treatment with rituximab and plasmapheresis have had mixed results.15-16 Though the most recent open label trial of rituximab given in 10 PAP patients demonstrated that it is well tolerated and improved oxygenation parameters up to six months after therapy and may have decreased the need for whole lung lavage. The exact mechanism of benefit is unclear but is likely related to clearing of the autoantibodies present in the lung.17 There is no role for glucocorticoids as therapy for PAP.

Follow up in our patient

The patient was followed in clinic after discharge. She continued to complain of an increased cough productive of clear mucus. She denied any changes in activity level or shortness of breath. PFTs were slightly worse than before. CT chest was concerning for increased bilateral densities. She had a GM-CSF antibody titer of 1:6400 which confirms acquired PAP (a 1:400 titer is considered abnormal).

She was given a 3 month trial of inhaled GM-CSF and seen in clinic after 3 months with repeat PFTs and CT chest. She denied any changes in symptoms. PFTs also were unchanged from those done 3 months prior. However, CT chest did look slightly worse with increased markings in the upper lobes.

She continued inhaled GM-CSF for another 3 months and sputum cultures for AFB, Nocardia and other pathogens were negative. After consulting with National Jewish Physicians, she was started on Mycophenolate mofetil orally advanced to the maximum dose of 3 gm/day. She has done well with improvement in her cough, lung function, six minute walk tests and CT scans and has not needed further whole lung lavage. There are currently no reports of using this drug in this condition and thus it warrants further study for proof of benefit. Our patient has done well thus far, but there is also a case report of Mycophenolate actually causing PAP when used as an immunosuppressant in a patient with Wegener’s Granulomatosis so caution when using this is advised.18

References

1. Shah, PL, Hansell, D, Lawson, PR, et al. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: Clinical aspects and current concepts on pathogenesis. Thorax 2000; 55:67.

2. Kariman, K, Kylstra, JA, Spock, A. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: Prospective clinical experience in 23 patients for 15 years. Lung 1984; 162:223.

3. Milleron, BJ, Costabel, U, Teschler, H, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage cell data in alveolar proteinosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991; 144:1330.

4. Inoue, Y, Trapnell, BC, Tazawa, R, et al. Characteristics of a large cohort of patients with autoimmune pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in Japan. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008; 177:752.

5. Claypool, WD, Rogers, RM, Matuschak, GM. Update on the clinical diagnosis, management, and pathogenesis of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (phospholipidosis). Chest 1984; 85:550.

6. Larson, RK, Gordinier, R. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. report of six cases, review of the literature, and formulation of a new theory. Ann Intern Med 1965; 62:292.

7. Beccaria, M, Luisetti, M, Rodi, G, et al. Long-term durable benefit after whole lung lavage in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Eur Respir J 2004; 23:526.

8. Seymour, JF, Dunn, AR, Vincent, JM, et al. Efficacy of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in acquired alveolar proteinosis [letter]. N Engl J Med 1996; 335:1924.

9. Barraclough, RM, Gillies, AJ. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: a complete response to GM-CSF therapy. Thorax 2001; 56:664.

10. De Vega, MG, Sanchez-Palencia, A, Ramirez, A, et al. GM-CSF therapy in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Thorax 2002; 57:837.

11. Kavuru, MS, Sullivan, EJ, Piccin, R, et al. Exogenous granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor administration for pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 161:1143.

12. Venkateshiah, SB, Yan, TD, Bonfield, TL, et al. An open-label trial of granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor therapy for moderate symptomatic pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Chest 2006; 130:227.

13. Seymour, JF, Doyle, IR, Nakata, K, et al. Relationship of anti-GM-CSF antibody concentration, surfactant protein A and B levels, and serum LDH to pulmonary parameters and response to GM-CSF therapy in patients with idiopathic alveolar proteinosis. Thorax 2003; 58:252.

14. Parker, LA, Novotny, DB. Recurrent alveolar proteinosis following double lung transplantation. Chest 1997; 111:1457.

15. Kavuru, MS, Bonfield, TL, Thomassen, MJ. Plasmapheresis, GM-CSF, and alveolar proteinosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 167:1036.

16. Borie, R, Debray, MP, Laine, C, et al. Rituximab therapy in autoimmune pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Eur Respir J 2009; 33:1503.

17. Kavuru MS, Malur A, Marshall I, Barna BP, Meziane M, Huizar I, Dalrymple H, Karnekar R, Thomassen MJ. An Open-Label Trial of Rituximab Therapy in Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis. Eur Respir J. Published on April 8, 2011 as doi: 10.1183/09031936.00197710.

18. Shah S, Phan N, Goyal G, Sharma G. Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis in a 67-Year-Old Woman with Wegener’s Granulomatosis. J Gen Intern Med. 2010; 25:1105.

Friday, February 24, 2012 at 3:27AM

Friday, February 24, 2012 at 3:27AM