The Emperor Has No Clothes: The Accuracy of Hospital Performance Data

Monday, October 8, 2012 at 6:45AM

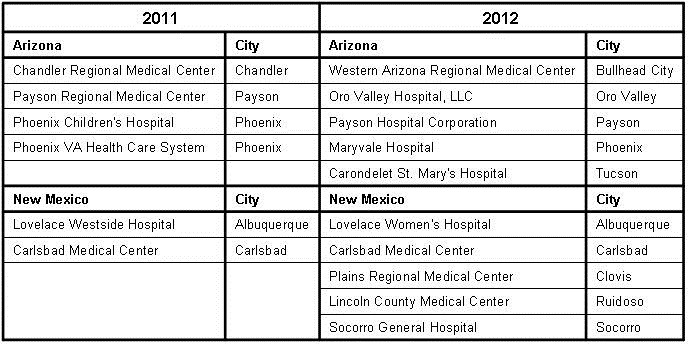

Monday, October 8, 2012 at 6:45AM Several studies were announced within the past month dealing with performance measurement. One was the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (Joint Commission, JCAHO) 2012 annual report on Quality and Safety (1). This includes the JCAHO’s “best” hospital list. Ten hospitals from Arizona and New Mexico made the 2012 list (Table 1).

Table 1. JCAHO list of “best” hospitals in Arizona and New Mexico for 2011 and 2012.

This compares to 2011 when only six hospitals from Arizona and New Mexico were listed. Notably underrepresented are the large urban and academic medical centers. A quick perusal of the entire list reveals that this is true for most of the US, despite larger and academic medical centers generally having better outcomes (2,3).

This raises the question of what criteria are used to measure quality. The JCAHO criteria are listed in Appendix 2 at the end of their report. The JCAHO criteria are not outcome based but a series of surrogate markers. The Joint Commission calls their criteria “evidence-based” and indeed some are, but some are not (2). Furthermore, many of the Joint Commission’s criteria are bundled. In other words, failure to comply with one criterion is the same as failing to comply with them all. They are also not weighted, i.e., each criterion is judged to be as important as the other. An example where this might have an important effect on outcomes might be pneumonia. Administering an appropriate antibiotic to a patient with pneumonia is clearly evidence-based. However, administering the 23-polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine in adults is not effective (4-6). By the Joint Commission’s criteria administering pneumococcal vaccine is just as important as choosing the right antibiotic and failure to do either results in their judgment of noncompliance.

Previous studies have not shown that compliance with the JCAHO criteria improves outcomes (2,3). Examination of the US Health & Human Services Hospital Compare website is consistent with these results. None of the “best” hospitals in Arizona or New Mexico were better than the US average in readmissions, complications, or deaths (7).

A second announcement was the success of the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research’s (AHRQ) program on central line associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) (8). According to the press release the AHRQ program has prevented more than 2,000 CLABSIs, saving more than 500 lives and avoiding more than $34 million in health care costs. This is surprising since with the possible exception of using chlorhexidine instead of betadine, the bundled criteria are not evidence-based and have not correlated with outcomes (9). Examination of the press release reveals the reduction in mortality and the savings in healthcare costs were estimated from the hospital self-reported reduction in CLABSI.

A clue to the potential source of these discrepancies came from an article published in the Annals of Internal Medicine by Meddings and colleagues (10). These authors studied urinary tract infections which were self-reported by hospitals using claims data. According to Meddings, the data were “inaccurate” and “are not valid data sets for comparing hospital acquired catheter-associated urinary tract infection rates for the purpose of public reporting or imposing financial incentives or penalties”. The authors propose that the nonpayment by Medicare for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired complications resulted in this discrepancy. There is no reason to assume that data reported for CLABSI or ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP) is any more accurate.

These and other healthcare data seem to follow a trend of bundling weakly evidence-based, non-patient centered surrogate markers with legitimate performance measures. Under threat of financial penalty the hospitals are required to improve these surrogate markers, and not surprisingly, they do. The organization mandating compliance with their outcomes joyfully reports how they have improved healthcare saving both lives and money. These reports are often accompanied by estimates, but not measurement, of patient centered outcomes such as mortality, morbidity, length of stay, readmission or cost. The result is that there is no real effect on healthcare other than an increase in costs. Furthermore, there would seem to be little incentive to question the validity of the data. The organization that mandates the program would be politically embarrassed by an ineffective program and the hospital would be financially penalized for honest reporting.

Improvement begins with the establishment of guidelines that are truly evidence-based and have a reasonable expectation of improving patient centered outcomes. Surrogate markers should be replaced by patient-centered outcomes such as mortality, morbidity, length of stay, readmission, and/or cost. The recent "pay-for-performance" ACA provision on hospital readmissions that went into effect October 1 is a step in the right direction. The guidelines should not be bundled but weighted to their importance. Lastly, the validity of the data needs to be independently confirmed and penalties for systematically reporting fraudulent data should be severe. This approach is much more likely to result in improved, evidence-based healthcare rather than the present self-serving and inaccurate programs without any benefit to patients.

Richard A. Robbins, MD*

Editor, Southwest Journal of Pulmonary and Critical Care

References

- Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/TJC_Annual_Report_2012.pdf (accessed 9/22/12).

- Robbins RA, Gerkin R, Singarajah CU. Relationship between the Veterans Healthcare Administration hospital performance measures and outcomes. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2011;3:92-133.

- Rosenthal GE, Harper DL, Quinn LM. Severity-adjusted mortality and length of stay in teaching and nonteaching hospitals. JAMA 1997;278:485-90.

- Fine MJ, Smith MA, Carson CA, Meffe F, Sankey SS, Weissfeld LA, Detsky AS, Kapoor WN. Efficacy of pneumococcal vaccination in adults. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Int Med 1994;154:2666-77.

- Dear K, Holden J, Andrews R, Tatham D. Vaccines for preventing pneumococcal infection in adults. Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2003:CD000422.

- Huss A, Scott P, Stuck AE, Trotter C, Egger M. Efficacy of pneumococcal vaccination in adults: a meta-analysis. CMAJ 2009;180:48-58.

- http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/ (accessed 9/22/12).

- http://www.ahrq.gov/news/press/pr2012/pspclabsipr.htm (accessed 9/22/12).

- Hurley J, Garciaorr R, Luedy H, Jivcu C, Wissa E, Jewell J, Whiting T, Gerkin R, Singarajah CU, Robbins RA. Correlation of compliance with central line associated blood stream infection guidelines and outcomes: a review of the evidence. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2012;4:163-73.

- Meddings JA, Reichert H, Rogers MA, Saint S, Stephansky J, McMahon LF. Effect of nonpayment for hospital-acquired, catheter-associated urinary tract infection: a statewide analysis. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:305-12.

*The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Arizona or New Mexico Thoracic Societies.

Reference as: Robbins RA. The emperor has no clothes: the accuracy of hospital performance data. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2012;5:203-5. PDF