What to Expect from Obamacare

Saturday, January 12, 2013 at 9:11AM

Saturday, January 12, 2013 at 9:11AM “I predict future happiness for Americans if they can prevent the government from wasting the labors of the people under the pretense of taking care of them.”

-Thomas Jefferson

The Supreme Court decision is in and the election is over. Obamacare, or the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), will become reality, but questions remain on what it will look like. ACA had three goals: 1. Expand coverage to the poor; 2. Control costs; and 3. Improve care. These are all laudable goals but it is unclear if they can be achieved. Experience from Federal-run health systems such as Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Veterans Administration (VA) provide some clues as do recent Federal actions and the Massachusetts health care system.

Expand Coverage to the Poor

The US has about 60 million uninsured and one of the ACA goals is to come as close as possible to achieving universal healthcare coverage. In order to do this, the ACA depends heavily on Medicaid, a joint Federal-state health benefits program, to reach the goal of near-universal health care. If every state participated, 17 million uninsured people would gain coverage through Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program between 2014 and 2022, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). These are often the poorest of the poor. The Federal government usually pays for about half to two-thirds of the cost of Medicaid. To encourage states to participate in the ACA, the Federal government upped payment to 100 percent of the cost of covering newly eligible people from 2014-6, after which the share will gradually go down to 90 percent in 2022 and later years.

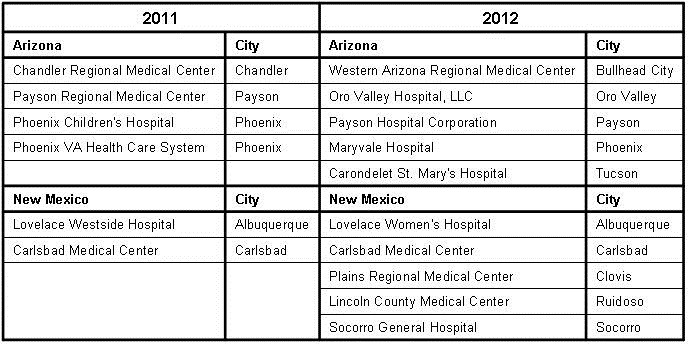

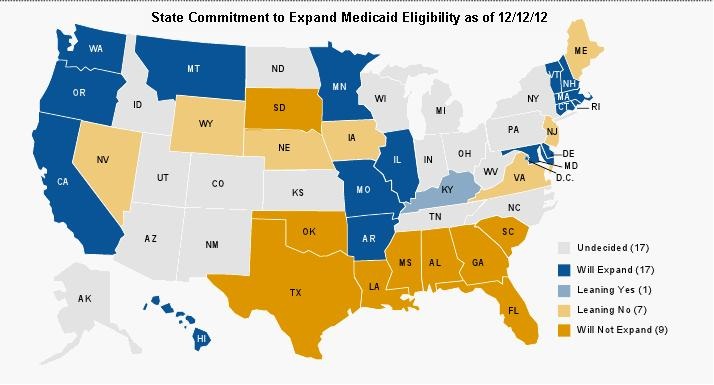

However, the Supreme Court decision in June, which mostly upheld the ACA, gave states the right to opt out of the Medicaid expansion. At the time of this writing, roughly a third of the states have decided not to participate, a third will participate and a third are undecided (Figure 1).

Figure 1. State commitment to expand Medicaid eligibility as of 12/12/12.

Some governors have asked Health and Human Services if they partially expand Medicaid will the Federal Government still pay for the expansion. In response, Health and Human Services Secretary, Kathleen Sebelius, has written a letter to the Nation’s governors saying it is all or nothing. According to the CBO this lack of participation leaves up to 3 million of the poorest Americans without health coverage. Placement of bureaucratic obstacles to discourage eligible persons not to sign up as well as political bickering and their inevitable subsequent lawsuits are likely to further delay care for the eligible. Therefore, it is unclear to what extent the ACA will increase coverage to the poor but it seems unlikely to bring the US any where close to universal healthcare.

Reduce Costs

Clearly medical care costs too much. In order to control the growth in costs it is necessary to know where the growth in spending has occurred. The latest data available is from 2010 and has been the subject of a previous editorial (2). Although there are many categories of health care expenditures, the four largest and their percentages of healthcare expenditures are hospital care (31.4%), physicians (16.1%), pharmaceuticals (10.0%), and net cost of insurance (5.6%). The largest increase in absolute costs was in hospitals which accounted for 39.4% of the increase of the $101.15 billion increase compared to 2009. The largest percentage increase was in net cost of insurance at 8.4% which was much higher than the 3.9% increase overall. Drug costs were not markedly increased at a1.2% increase but the top 12 companies had 310.8 billion in sales and 49.3 billion in profits in 2012 suggesting that the pharmaceutical industry is healthy and profitable (3). Although the Obama Administration often talks tough about reducing costs, especially insurance company costs, it seems unlikely based on their history that there will be a reduction in any of these three categories.

On the other hand, physician salaries have fallen. While the income of dentists, pharmacists, registered nurses, physician assistants, and health care and insurance executives rose by an average 10.2% in 2005-10 compared 2000-4, the income of physicians decreased by 5.8% (4). Although the hourly wage of physicians remains high ($80.00/hr) and remains higher than dentists ($70.64/hr) and lawyers ($54.21/hr), the gap is closing (5-7). This is despite a shortage of physicians (5). Even though the greatest physician need is in primary care physicians, pediatricians, family practioners and general internists remain the lowest paid physicians (8).

Based on these trends, it seems likely medical costs will continue to rise. However, payments to physicians will probably remain static or decrease. Although the consequences are unclear, the cuts in payment to physicians are not sustainable and will likely drive many physicians, especially primary care physicians, out of private practice. The other consequence may be that some physicians, most likely specialists, may not take insurance with low reimbursement such as Medicare and Medicaid. This would mean that those that can afford to pay out of pocket will receive health care while the poor, the very people the ACA was intended to help, may not. Regardless, it is unlikely that the continual focus on physician reimbursement to control costs will be successful in controlling overall medical expenditures. The 16.1% of healthcare costs attributable to physicians is simply not large enough to reduce the overall costs, especially since physicians have born the brunt of the cuts for the past few years.

The ACA also proposes to reduce costs by paying only for value- and evidence-based care based more for outcomes than procedures. However, this is the approach that has been in place for some time at CMS and has yet to reduce costs. Committees far removed from medical practice have often made poor decisions. For example, patients who need self-catherization were at one time allowed only 4 catheters per month. Some patients had excessive and expensive hospital admissions for urinary tract infections. Presumably the catheters were not properly cleaning their catheter prior to reuse which resulted in the excess hospitalizations. The policy has now been changed to allow up to 200 catheters per month.

Another example is computerized healthcare records. In a January speech, President Obama evoked the promise of new technology: “This will cut waste, eliminate red tape and reduce the need to repeat expensive medical tests," he said. However, rather than reduce costs, the opposite happened. With better documentation, physicians billed at higher levels actually increasing costs (9). Response blaming physicians was swift implying physicians committed fraud (10).

Physicians and their patients may find themselves directed to cheaper care even when evidence points to a better but more expensive alternative. As a personal example, I have congestive heart failure and take carvedilol. My insurance company, Blue Cross and Blue Shield, has denied payment for the carvedilol despite evidence that it is superior to their recommended alternative, metropolol (11). The VA and Medicare have had similar policies in place. The difference in cost is about $1/day. I pay for my carvedilol out-of-pocket because in the COMET trial it reduced mortality from 40% to 34% (11). My judgment was that a 6% increase in survival was worth the extra cost. Patients are likely to find themselves in similar situations where if they want care that is not in the guidelines, they will need to pay for it themselves whether it is evidence-based or not.

Improvement in Care

A clue to how the Obama administration plans to improve care was in the 2010 summer recess appointment of Don Berwick as Administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Prior to his appointment he was President and Chief Executive Officer of the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI). IHI was a group who convinced many hospitals to adopt a number of their guidelines. These guidelines had two common themes-most were physician focused and many very weakly evidence-based (12,13). CMS began tying reimbursement and compliance with the guidelines. The financial disincentive to accurately report data induced many hospitals to lie about their data (14). Not surprisingly, compliance improved but there has been little evidence for an accompanying improvement in outcomes (14,15). Witness the recent example of central line associated blood stream infections (CLABSI). Based on hospital self-reported data, CMS announced its program reduced the rate of CLABSI (16). Within a month an article appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine reporting the program did nothing to reduce infections or any other outcomes (17).

However, there may be a glimmer of hope. Although there is a continued reliance on weakly evidence-based surrogate markers, CMS has begun looking at mortality, morbidity, length of stay and readmission rates. These patient-centered outcomes have real meaning to patients as well as affecting costs. This may finally force health care administrators to address real care issues rather than performance of surrogate, weakly evidence based guidelines such as administration of pneumococcal vaccine to adults, telling smokers not to smoke without any follow up and providing discharge instructions.

Conclusions

Overall it appears that the ACA will have minimal impact on its goals of expanding care to the poor, reducing costs or improving care for the foreseeable future. It will likely continue to cost shift reimbursement away from physicians while costs continue to rise. Almost certainly it will be entangled in political bickering, eligibility challenges and lawsuits reducing many of the benefits of the law. However, we can probably be assured that CMS will continue to rely on inaccurately reported data, quickly declare their programs successful and stay their course, despite the programs doing little to nothing for patients. When their programs focus on outcomes such as mortality, morbidity, length of stay and readmission rates, real progress can be made in improving patient care rather than “spinning” dubious results.

Richard A. Robbins, MD*

References

- Kliff S. White House to states: on Medicaid expansion, it’s all or nothing. Available at http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2012/12/10/white-house-to-states-on-medicaid-expansion-its-all-or-nothing/ (accessed 12-13-12).

- Robbins RA. Follow the money. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2012;4:19-21.

- Fortune. Available at: http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune500/2012/industries/21/ (accessed 12-13-12).

- Seabury SA, Jena AB, Chandra A. Trends in the earnings of health care professionals in the United States, 1987-2010. JAMA 2012;308:2083-5.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Avaiable at: http://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physicians-and-surgeons.htm (accessed 12-13-12).

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/dentists.htm (accessed 12-13-12).

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Available at http://www.bls.gov/ooh/legal/lawyers.htm (accessed 12-13-12).

- Medscape. Physician compensation report 2012. Avaiable at: http://www.medscape.com/sites/public/physician-comp/2012 (accessed 12-13-12).

- Haig S. Electronic medical records: will they really cut costs? Time 2009. Available at: http://www.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1883002,00.html#ixzz2FF0XBf5d (accessed 12-16-12).

- Carlson J. HHS inspector general's office quizzes providers about EHR use. Modern Healthcare 2012. Available at: http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20121023/NEWS/310239946 (accessed 12-13-12).

- Poole-Wilson PA, Swedberg K, Cleland JG, Di Lenarda A, Hanrath P, Komajda M, Lubsen J, Lutiger B, Metra M, Remme WJ, Torp-Pedersen C, Scherhag A, Skene A; Carvedilol Or Metoprolol European Trial Investigators. Comparison of carvedilol and metoprolol on clinical outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure in the Carvedilol Or Metoprolol European Trial (COMET): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003 ;362:7-13.

- Padrnos L, Bui T, Pattee JJ, Whitmore EJ, Iqbal M, Lee S, Singarajah CU, Robbins RA. Analysis of overall level of evidence behind the Institute of Healthcare Improvement ventilator-associated pneumonia guidelines. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2011;3:40-8.

- Hurley J, Garciaorr R, Luedy H, Jivcu C, Wissa E, Jewell J, Whiting T, Gerkin R, Singarajah CU, Robbins RA. Correlation of compliance with central line associated blood stream infection guidelines and outcomes: a review of the evidence. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2012;4:163-73.

- Meddings JA, Reichert H, Rogers MA, Saint S, Stephansky J, McMahon LF. Effect of nonpayment for hospital-acquired, catheter-associated urinary tract infection: a statewide analysis. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:305-12.

- Robbins RA. The emperor has no clothes: the accuracy of hospital performance data. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2012;5:203-5.

- Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/clabsiupdate/ (accessed 12-13-12).

- Lee GM, Kleinman K, Soumerai SB, Tse A, Cole D, Fridkin SK, Horan T, Platt R, Gay C, Kassler W, Goldmann DA, Jernigan J, Jha AK. Effect of nonpayment for preventable infections in U.S. hospitals. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1428-37.

*The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Arizona, New Mexico or Colorado Thoracic Societies.

Reference as: Robbins RA. What to expect from Obamacare. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2013;6(1):23-28. PDF