Why Complexity Persists in Medicine

Monday, February 3, 2020 at 11:11AM

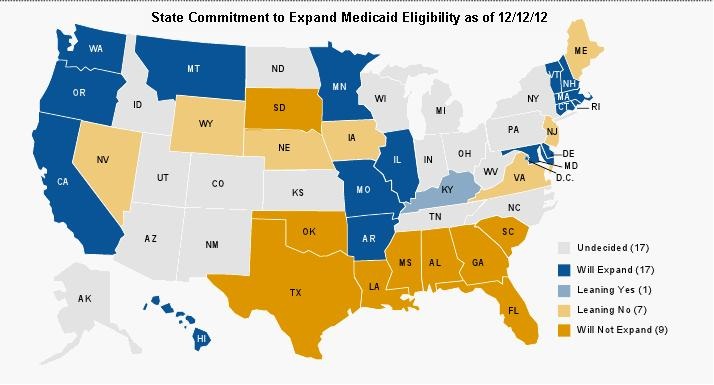

Monday, February 3, 2020 at 11:11AM This month’s Medical Image of the Month is a cartoon illustrating the complexity of medical billing (1). It illustrates that there are many people involved in the billing process who add nothing medically. However, they do add work, chaos and cost to both the provider and the patient. These along with other administrative costs are likely responsible for the largest portion of increasing healthcare expenses (2). Healthcare costs have far outpaced inflation and inflation adjusted reimbursement to providers has decreased (3,4). Costs of healthcare have become an increasing issue in political campaigns for both National parties. So why is no one doing anything about the issue? The truth is that some are benefitting from the complexity and have a financial incentive to maintain the status quo by opposing change.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and state Medicaids need to accept some of the responsibility for these cost increases. There has been a public sentiment doctors are overpaid, so actions taken by CMS and other government agencies have made physicians an easy target for policies that have led to instability in compensation. The declining income of private practice has led many physicians to flee to employed models (4). Not only has CMS contributed to driving physicians from self-employment by underpaying independent physicians but they have over compensated physician employed by hospitals. CMS estimates that it is now paying about $75 to $85 more on average for the same clinic visit in hospital outpatient settings compared to physician offices (5). Not surprisingly, these and other compensation disproportions have led to higher healthcare spending (6).

So, why does CMS rob the independent physicians to pay the hospitals and large healthcare organizations? An answer might be found in the recent actions regarding site-neutral payments. Many hospitals have bought physician and walk-in clinics to take advantage of the increased compensation from CMS and other insurance carriers. When the Trump administration proposed a “site-neutral” policy where payment would be lowered to hospitals and other healthcare organizations employing physicians, the American Hospital Association (AHA) and Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) sued (7). Government agencies are reluctant to challenge hospital, insurance or pharmaceutical companies and their lobbyists who are powerful and well-funded. This gives the appearance that it is much easier to be tough on independent physicians who are poorly organized, politically weak and not likely to sue.

Political tactics have been taken by the pharmaceutical companies who persuaded Congress not to allow US agencies such as CMS and the Department of Veterans Affairs to negotiate drug prices. It was in 2003, under then President George W. Bush, that Congress added a Part D benefit, through which CMS pays for seniors’ prescription drugs. The enactment followed a controversial House roll call vote, which was held open for several hours as House leaders maneuvered to secure enough votes for passage. One bargaining chip to attract votes from “market-oriented” Congressmen was the so-called “noninterference clause” which banned negotiations between CMS and pharmaceutical companies on drug prices and prevented the government from developing its own formulary or pricing structure. In other words, US Government agencies are forced to pay whatever prices the manufacturers set (8).

Sadly, our professional societies have also contributed to rising healthcare costs. An example is the Joint Commission which was formed in 1951 by merging the Hospital Standardization Program with similar programs run by the American College of Physicians, the American Hospital Association (AHA), the American Medical Association, and the Canadian Medical Association. However, the Joint Commission has become dominated the American Hospital Association which has continually pushed a hospital administrative agenda (9). Standards leading to or encouraging administrative efficiency appear nonexistent. Even our own professional societies have fixated on programs such as Choosing Wisely which emphasizes physicians not performing unnecessary testing or procedures. Although this is important for our patients, it is has not, nor is likely to, make any difference in healthcare costs.

All this is occurring at a time when the hospital-private practice physician partnership has largely dissolved. Hospitals want employed physicians because of the financial benefits of higher reimbursement but also because physicians as employees are much easier to control. As hospitals hire their own physicians, often in open competition with private practice physicians on their staff, the hospitals and private practice physicians are no longer partners but adversarial competitors. It is naïve to believe that hospitals will not take advantage of their position of power to eliminate the private practice competition or make changes to a system such as the complex reimbursement system which has benefited them so greatly. Even something so basic as stating the cost of a procedure has been vigorously opposed by the AHA (10). Similarly, the pharmaceutical industry has opposed transparency or government negotiation on drug prices (11). And why should the any of these healthcare administrators, pharmaceutical companies or insurance companies agree to any change? They are growing rich at the American public’s expense.

Rather than throwing up our hands in disgust or going to our windows, opening them and sticking our heads out to yell – “I'm as mad as hell and I'm not gonna take this anymore!” it is time to do something. However, as physicians we need to realize that we are weak and need help. First, we need to elect political candidates at all levels of government not based on their political affiliation but on their willingness to take action to curb healthcare costs. Second, if the politicians do not take action, we need to hold them accountable by voting for someone else. Third, we should lobby through our professional societies that administrative change needs to happen. If the societies will, we either need to serve in a society leadership role or change the leadership. Fourth, we need to oppose actions to further intrude into or control the practice of medicine at the local hospital level. For example, physician leaders are often chosen by the hospital administration not for their abilities by their amenability to a hospital administration’s agenda. As physicians we have let healthcare become controlled by greedy businessmen and correcting their intrusion into medical practice will be difficult. However, we should maintain hope, the alternative simply costs too much.

Richard A. Robbins, MD

Editor, SWJPCC

References

- Umar A, Robbins RA. Medical image of the month: complexity of healthcare payment. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2020;20(2):59. [CrossRef]

- Robbins RA. National health expenditures: the past, present, future and solutions. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2015;11(4):176-85. [CrossRef]

- Kacik A. Rising prices drive estimated 6% medical cost inflation in 2020. Modern Healthcare. June 20, 2019. Available at: https://www.modernhealthcare.com/providers/rising-prices-drive-estimated-6-medical-cost-inflation-2020 (accessed 1/30/20).

- Morris SS, Lusby H. The physician compensation bubble is looming. American Association of Physician Leadership. January 16, 2019. Available at: https://www.physicianleaders.org/news/physician-compensation-bubble-looming (accessed 1/30/20).

- Dickson V. CMS slashes clinic visit payments, expands 340B cuts. Modern Healthcare. November 2, 2018. Available at: https://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20181102/NEWS/181109978 (accessed 1/30/20).

- Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Kessler DP. Vertical integration: hospital ownership of physician practices is associated with higher prices and spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014 May;33(5):756-63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terry K. Court overturns CMS' site-neutral payment policy; doc groups upset. Medscape Medical News. September 19, 2019. Available at: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/918744?nlid=131645_5401&src=wnl_dne_190920_mscpedit&uac=9273DT&impID=2101100&faf=1#vp_2 (accessed 1/31/20).

- Lee TL, Gluck AR, Curfman GD. The politics of Medicare and drug-price negotiation (updated). Health Affairs Blog. September 19, 2016. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20160919.056632/full/ (accessed 1/31/20).

- Gaul GM. Accreditors blamed for overlooking problems. Washington Post. 2005. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/07/24/AR2005072401023.html (accessed 2/1/20).

- Evans M. Hospitals turn to courts as lobbying fails to block price-transparency proposal. The Wall Street Journal. December 5, 2019. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/hospitals-turn-to-courts-as-lobbying-fails-to-block-price-transparency-proposal-11575551412 (accessed 2/1/20).

- Parramore LS. Prescription drug costs in Americans are sky-high. And yes, Big Pharma greed is to blame. NBC News. January 2, 2020. Available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/think/opinion/prescription-drug-costs-americans-are-sky-high-yes-big-pharma-ncna1109076 (accessed 2/1/20).

Cite as: Robbins RA. Why complexity persists in medicine. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2020;20(2):60-2. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc006-20 PDF