The Implications of Increasing Physician Hospital Employment

Monday, May 13, 2019 at 8:00AM

Monday, May 13, 2019 at 8:00AM Several years ago, Dr. Jack had a popular, solo internal medicine practice in Phoenix. However, over a period of about 15-20 years, the profitability of Jack’s private practice dwindled and he was working 60+ hours per week to keep his head above water. This is not what he planned in his mid-50’s when he hoped to be settling into a comfortable lifestyle in anticipation of retirement. Jack eventually closed his practice and took a job as a hospital-employed physician. Jack’s story has become all too common. The majority of physicians are now hospital-employed (1).

The increase in hospital-employed physicians raises at least 2 questions: 1. How can a busy private practice not be profitable? and 2. Is it good to have most physicians hospital-employed? Like Jack, it seems most physicians seek hospital employment for financial and lifestyle reasons. But how can a primary care practice like Jack’s not be profitable when the cost of healthcare has risen so markedly?

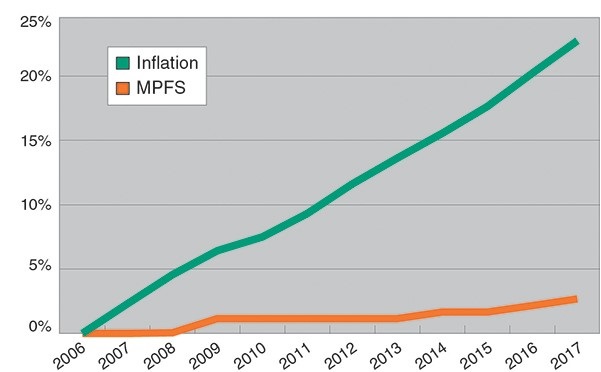

To understand why a practice can be busy but not necessarily profitable we need to follow the money. First, reimbursement for private practice has decreased in real dollars (Figure 1) (2).

Figure 1. Inflation and Medicare physician fee schedule (MPFS) growth in percent from 2006-2017 (2).

Private practice physician reimbursement is the only major cost center that the Centers and Medicaid Services (CMS) has singled out for asymmetrical negative annual fee schedule adjustments. The other major cost centers—hospital inpatient and outpatient, ambulatory surgical centers, and clinical laboratories—all had fee schedule adjustments that were nearly equal to and typically greater than inflation (2). Of course, private insurance companies follow CMS’ lead and so reimbursement to private practice physicians dramatically decreased (3).

In addition, increased requirements for documentation and paperwork were imposed by CMS and quickly picked up by private insurers. These required more physician time and/or the hiring of additional personnel. In addition, there were increasing annoyances and burdens placed on physicians to review and sign forms and prescriptions which already been electronically submitted. Often these annoyances were so the durable medical equipment provider, pharmacy, etc. could be reimbursed. These later burdens now take up to one-sixth of a physicians’ time, decrease office efficiency, and not surprisingly, greatly decrease physician job satisfaction (4).

The second question is whether hospital-employed physicians is a good thing for patients. Although hospitals have argued that hospital-based physicians provide better care, patient outcomes appear to be no different (5). Hospitals have engaged in a number of practices resulting in physicians being financially squeezed. The American Hospital Association (AHA) has lobbied CMS and Congress for payments that are much higher than independent physicians’ offices, assuring hospital profitability. However, under the Trump administration, CMS proposed to pay the same rate for services delivered at off-campus hospital outpatient departments and independent doctors' offices (called site neutrality) (6). This would result in about a 60% cut to the hospitals for these services (7). Not surprisingly, hospitals complained and lobbied Congress to rescind the rule (7). Later the AHA sued CMS challenging the "serious reductions to Medicare payment rates" as executive overreach (8). The case is currently pending before the courts.

Hospitals have also engaged in a number of practices to limit competition from physicians’ offices. First, several have employed a non-compete clause as a condition of obtaining staff privileges. These clauses mean that should a physician leave a hospital, the physician is unable to reestablish a practice within a specified distance of the hospital (often within a radius of 50 miles) (9). Of course, in a metropolitan area this means the physician has to leave the city, or in the case of a large hospital chain, the physician may have difficulty finding areas to practice even in the same state. Second, with the “hospitalist movement” many hospitals have seized on the opportunity to essentially self-refer. That is, the hospitals schedule follow-up appointments with primary care or other physicians employed by the hospitals.

A study documents that healthcare costs for four common procedures rose with increasing hospital physician employment (10). A 49% increase in hospital-employed physicians led to CMS paying $2.7 billion more for diagnostic cardiac catheterizations, echocardiograms, arthrocentesis and colonoscopies delivered in hospital outpatient settings than it would for treatment in independent facilities. CMS beneficiaries footed an additional $411 million.

Although many decry a fee-for-service healthcare system as being too expensive, the increase in hospital-employed physicians seems to only have increased healthcare costs. Action by CMS is needed not only for site neutrality but also a number of other areas to ensure health competition in healthcare.

Richard A. Robbins, MD

Editor, SWJPCC

References

- Kane CK. Updated data on physician practice arrangements: For the first time, fewer physicians are owners than employees. Policy Research Perspectives. American Medical Association. 2019. Available at: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-05/prp-fewer-owners-benchmark-survey-2018.pdf (accessed 5/11/19).

- Cherf J. Unsustainable physician reimbursement rates. AAOS Now. October, 2017. Available at: https://www.aaos.org/AAOSNow/2017/Oct/Cover/cover01/ (accessed 5/11/19).

- Clemens J, Gottlieb JD. In the shadow of a giant: Medicare's influence on private physician payments. J Polit Econ. 2017 Feb;125(1):1-39. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU. Administrative work consumes one-sixth of U.S. physicians' working hours and lowers their career satisfaction. Int J Health Serv. 2014;44(4):635-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Short MN, Ho V. Weighing the effects of vertical integration versus market concentration on hospital quality. Med Care Res Rev. 2019 Feb 9:1077558719828938. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins RA. CMS decreases clinic visit payments to hospital-employed physicians and expands decreases in drug payments 340b cuts. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2018;17(5):136. [CrossRef]

- Luthi S, Dickson V. Medicare's site-neutral pay plan targeted in hospitals' lobbying. Modern Healthcare. September 25, 2018. Available at: https://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20180925/TRANSFORMATION04/180929928/medicare-s-site-neutral-pay-plan-targeted-in-hospitals-lobbying (accessed May 11, 2019).

- Luthi S. Hospitals sue over site-neutral payment policy. Modern Healthcare. December 04, 2018. Available at: https://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20181204/NEWS/181209973/hospitals-sue-over-site-neutral-payment-policy (accessed May 11, 2019).

- Darves B. Restrictive covenants: A look at what’s fair, what’s legal and everything in between, Today’s Hospitalist. April 2006. Available at: https://www.todayshospitalist.com/restrictive-covenants-a-look-at-whats-fair-whats-legal-and-everything-in-between/ (accessed May 11, 2019).

- Kacik A. Hospital-employed physicians drain Medicare. Modern Healthcare. November 14, 2017. Available at: https://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20171114/NEWS/171119942/hospital-employed-physicians-drain-medicare (accessed May 11, 2019).

Cite as: Robbins RA. The implications of increasing physician hospital employment. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2019;18(5):141-3. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc025-19 PDF