Credibility and (Dis)Use of Feedback to Inform Teaching : A Qualitative Case Study of Physician-Faculty Perspectives

Saturday, June 27, 2015 at 9:01AM

Saturday, June 27, 2015 at 9:01AM Tara F. Carr, MD

Guadalupe F. Martinez, PhD

Division of Pulmonary/Critical Care, Sleep and Adult Allergy

Departments of Medicine and Otolaryngology

University of Arizona College of Medicine

Tucson, AZ

Abstract

Evaluation plays a central role in teaching in that physician-faculty theoretically use evaluations from clinical learners to inform their teaching. Knowledge about how physician-faculty access and internalize feedback from learners is sparse and concerning given its importance in medical training. This study aims to broaden our understanding. Using multiple data sources, this cross-sectional qualitative case study conducted in Spring of 2014 explored the internalization of learner feedback among physician-faculty teaching medical students, residents and fellows at a southwest academic medical center. Twelve one-on-one interviews were triangulated with observation notes and a national survey. Thematic and document analysis was conducted. Results revealed that the majority accessed and reviewed evaluations about their teaching. Most admitted not using learner feedback to inform teaching while a quarter did use them. Factors influencing participants use or disuse of learner feedback were the a) reporting metrics and mechanisms, and b) physician-faculty perception of learner credibility. Physician-faculty did not regard learners’ ability to assess and recognize effective teaching skills highly. To refine feedback for one-on-one teaching in the clinical setting, recommendations by study participants include: a) redesigning of evaluation reporting metrics and narrative sections, and b) feedback rubric training for learners.

Introduction

Teaching is at the heart of academic medicine. Evaluation plays a central role in teaching in that clinical teachers, theoretically use evaluations from learners to inform their teaching (1,2) Feedback has been identified as a critical component of evaluation, and by extension, medical education training (3-6). National accreditation agencies emphasize the need for the ongoing meaningful exchange of feedback between learners and physician-faculty (7,8)

The learner perspective has dominated feedback research (9-14). These studies examine how physician-faculty deliver feedback, and how learners absorb the content and delivery of feedback. Physician-faculty also assume the role of learner when medical students and trainees serve as evaluators and provide feedback about physician-faculty teaching. In response, physician-faculty develop perceptions about the quality and context of feedback from learners that shape their receptiveness of that feedback, and teacher self-efficacy (15-18). Yet, only four studies consider context and explore factors that influence feedback receptiveness of physician-faculty (15, 19-21). Only one study examines how physician-faculty respond to learner feedback to make adjustments to their teaching (15). Previous studies have also uncovered the important idea of “source credibility." (11,14,20,22). They find that the impetus for both effective learning and teaching adjustment comes from the feedback recipient’s trust in the evaluators’ credibility. A limitation of these studies is the lack of attention to the feedback reporting mechanisms used by their institutions, leaner-teacher contact time, the establishment of relationships, and the various factors that go into trusting or valuing learner feedback. These perceptions play an essential role in how we understand educational exchanges between teacher and learner. As such, the purpose of this study is to recognize physician-faculty perceptions about the feedback process in relationship to their teaching practice.

Knowledge about how physician-faculty access and internalize feedback from learners is sparse (22), much less faculty recommendations for improving the process. This is concerning given the important role feedback plays in clinical training. This study aims at broadening the understanding of how physician-faculty access and internalize written feedback from learners while considering contextual factors that shape the overall feedback experience for physician-faculty. We qualitatively examine if and how learner feedback influences physician-faculty receptivity and incorporation of feedback critiques into their teaching practice. In supporting inquiries, we ask: To what extent do physician-faculty access and use feedback and why (or why not)? What factors shape their decisions to incorporate (or not incorporate) learner feedback into their teaching practice?

Methods

Exempt from human research approval by the site’s Institutional Review Board, this cross-sectional case study explored feedback internalization among medicine physician-faculty at a southwest academic medical center (23). The ethical conduct to maintain anonymity and inhibit coercion was exercised and articulated to participants. Participation was voluntary and without monetary compensation.

Case study research in the social science calls for the use of multiple data sources to gain understanding of an issue using a bounded group (24,25). As such, three data sources were included in analysis and to triangulate findings. First, purposeful selection was used to identify physician-faculty whose lived experiences in the department would assist us in understand the issue (26). Physician-faculty were introduced to the study’s purpose at a routine faculty meeting where voluntary participation was elicited.

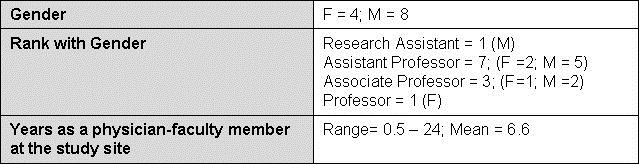

Twelve of 15 (80%) full-time medicine subspecialists participated. Sometimes mistaken as a limitation of qualitative case study design is the relative small sample size; our interview numbers not only meet the general qualitative research sample size criterion of five to 30 interviews (27-30) but focuses on obtaining information-richness in the form of quality, length and depth of interview data and supporting evidence from additional sources that answer the research question. (Table 1).

Table 1. Sample Demographics.

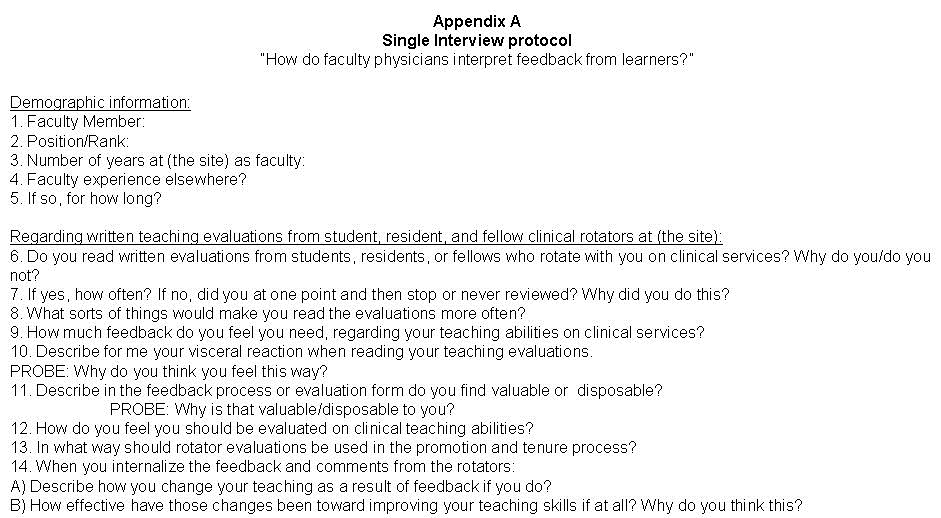

Original interview questions were created (Appendix A). Individual semi-structured open ended interviews were conducted during the Spring of 2014. Follow-up interviews on two participants were conducted in early February of 2015 once promoted from mid-level to full professor. The same interview protocol was used to capture changes in perspective from full professors in the effort to expand the insight pool of senior professors.

During the preceding three years, all physician-faculty in the department received e-feedback at the end of rotations from learners that includes evaluation of their individual teaching. E-feedback was designed by the college’s medical education program directors. Forms were 9-point Likert scale with an optional written comments section after each question. To gather information regarding the internalization of feedback, we asked physician-faculty to recollect past e-feedback through their tenure at the study site. Interview questions asked participants to describe their access to evaluations, and internalizations of feedback. Interviews lasted between 30-60 minutes, were audio recorded, and transcribed. Transcripts were de-identified, and demographic information reported was limited. Reporting of narratives was truncated to capture central points and stay within the word count limitation. Participants from outside institutions and departments were not included in this study as evaluation tools may include different reporting mechanisms. Additionally, we wanted to capture and understand the current subculture that exists regarding feedback and teaching that is particular to one local clinical department.

Secondary data were: observation notes, and annual ACGME trainee survey results. Observation notes were taken by the principal investigator to memorialize each interview exchange, physician-faculty education meetings (e.g. faculty meetings, clinical competency committee meetings), and clinic exchanges also during Spring of 2014 (31). Given that the principal investigator is also a physician-faculty member, an insider researcher approach (32) allows the design to include her notations as she is acutely attuned to the daily lived experiences of the participating physician-faculty. The advantage of implementing this approach is that the principal investigator understands the participants’ academic values, current work environment, insider language and cues for accurate and trustworthy behavioral notes. Observation notes were taken to document behavior at education meetings where program evaluation and physician-faculty development was discussed. Disadvantages of being an insider could lead to bias, assumptions about meanings, and overlooking of routine behaviors that could be important. A quasi-outside researcher and non-physician-faculty member in the department served as a collaborator to counter insider researcher assumptions and bias.

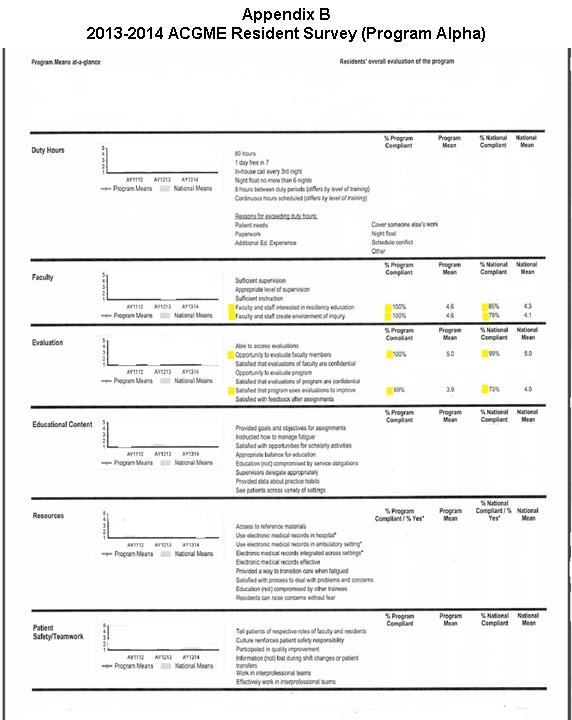

Physician-faculty interviewed also partook in the 2013-2014 annual ACGME anonymous online trainee survey in the Spring of 2014. Trainee ratings of physician-faculty commitment to GME programs, and perceived satisfaction the program’s perceived use of evaluations to improve rotations could further validate whether or not physician-faculty use evaluations to inform their teaching. (Appendix B).

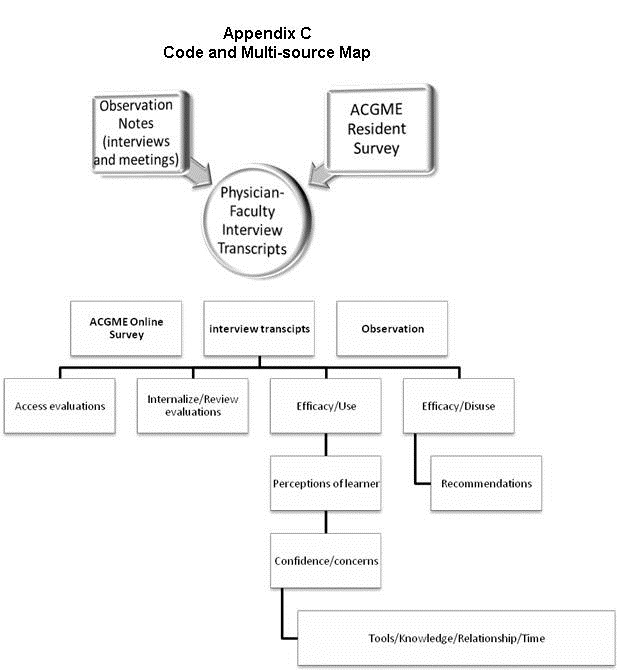

Data were analyzed using qualitative software, QSR Nvivo10©. Using a holistic and cross-case analysis approach (25), thematic coding was used to identify patterns in access to feedback, and receptiveness on interview data and observation notes. Axial coding was then used to hone in on specific challenges/strengths in feedback from learners. Once identified, selective coding was conducted to detect themes and redundant assertions so as to ensure that no new information was emerging. Last, document analysis of the ACGME survey results was conducted. Implementing the In-between-triangulation method (33), codes from observation notes and the ACGME survey results were linked through memos to interview data. Member checking between the principal investigator and co-investigator regarding themes, terms, and categorizations occurred to ensure data trustworthiness as defined by Guba (34) (Appendix C).

Results

Access, review, and (dis)use

A significant proportion of physician-faculty accessed and reviewed feedback about them when available (10/12: 83%). The majority of physician-faculty revealed that they do not use learner feedback to make adjustments to their teaching (9/12; 75%). One physician-faculty member summarized the group’s sentiments and disclosed,

“Not at all. The verbal feedback from my colleagues and boss makes me more cognizant of my behavior and I modify it appropriately; whether it was a success, I’ll let them judge. The written eval[uation]s from [learners] has never changed [my teaching] because they go from horrible to great and they are not useful.”-S11

Only a quarter, all of whom were junior faculty, reported utilizing learner feedback to alter teaching (3/12; 25%). Evidence that the majority of physician-faculty may not be using learner feedback to adjust teaching is broadly, but further corroborated by the ACGME survey data. Although 100% of trainees in this GME program reported having the opportunity to evaluate physician-faculty, less than 70% (which was very close to the national average) reported satisfaction with the program and physician-faculty using learner evaluations to improve. Despite this rating, these learners also reported that physician-faculty were interested in the educational program, and created an environment of inquiry at the rate of 100% (Appendix B). Furthermore, from observation notes taken during daily clinical discussions, it was noted that physician-faculty did not discuss their weaknesses with each other; especially regarding their teaching skills. Finally, when conversations regarding national conferences arose in physician-faculty education meetings or informal social settings, physician-faculty did not dialogue about attending conferences for the specific reason of improving or learning new teaching skills.

Factors influencing (dis)use

Physician-faculty identified several factors shaping their decisions to incorporate learner feedback into their teaching. To begin, just over half (7/12; 58%) reported that the metric used was problematic. When asked what they found valuable or disposable in reporting mechanisms, physician-faculty attested:

“A one-to-one evaluation rather than [the software we use] would be more valuable because…the numerical feedback is not very good. They need directed questions. There are non-substantive comments.” - S11

“The numbers are worthless. I’d rather get comments that say,’ the bedside teaching was excellent, but he should work on his didactic session and change the graphics on that PowerPoint,’ but I never get that.” - S04

Second, differences in the perception of the learners emerged. Observation notes documenting contact time, relationship establishment and perspectives on fellows, specifically, revealed that physician-faculty tended to label learners in “good/bad” categories based on a combination of professional conduct, and medical knowledge base. “Good fellows” were the desired learner in the clinical setting. These learners were discussed and seen frequently in the company of physician-faculty at grand rounds, academic half days and departmental social gatherings. From observation, five physician-faculty had a following of learners who were similar to them in personality traits, interests or career aspirations. These physician-faculty and learners had a relationship, and it was evident at both social and academic gatherings as evident by the quality, duration and topic of verbal engagement, and physical proximity. Not all physician-faculty observed had this type of following and engagement.

Expanding on the observation of categorization and relationship establishment, physician-faculty reflected on their overall experience with learners and reported a general concern with the learners serving as evaluators. As a result, they cited this as a major reason for the disuse of feedback to inform their teaching (9/12; 75%). Concerns were grounded in the context of a) inadequate contact time, b) learners’ teaching fund of knowledge, and c) feedback being foregrounded in whether or not the learner takes a personal liking to the attending. When asked what their visceral reaction was to learner feedback, physician-faculty stated,

“I think you should limit it to somebody who has prolonged exposure to you. Most [learners] are only exposed to you for a few days…I think it’s more about the person doing the eval[uation] than the faculty member’s teaching ability. So I don’t hold learner feedback in high regard.” - S07

“I don’t think they know what a good teacher is….most [learners] just anchor their eval[uation] based on whether they like someone or not, so there’s not a rigorous evaluation of teaching methods.”- S04

These issues relate to physician-faculty skepticism about learners’ abilities to assess the teaching skills of their attending. There was a perception that learners were either: a) not knowledgeable about teaching methods and feedback, or b) scared to give honest feedback to physician-faculty because of the fear of retaliation. Nearly all physician-faculty reporting concerns with learner feedback knowledge recommended they receive a rubric as a tool to not only guide their feedback, but educate them about the evaluation process, and help identify “teaching moments” (7/9; 78%). Physician-faculty remarked,

“They might not know when the teaching is happening… I don’t think they know how that works and what that standard is... they don’t notice it…a lot of the teaching can be seen as unconventional. A rubric for them might be helpful…they need to be educated on evaluation.“- S10

Conversely, only two physician-faculty reported using learner feedback to adjust their teaching (2/9; 22%). They noted,

“[Learners] have been exposed to a lot of teaching and have a sense of what is effective and works for them. So part of our job is to be an effective teacher for different learners so if we’re not an effective teacher for certain learners we need to know about that…in a sense everyone is qualified… It doesn’t mean that one person who says you are not an effective educator is correct. We can’t please everyone, but we can work towards it.”- S11

“…I try to establish relationships with the residents and fellows, and unfortunately or fortunately, it is easier for me to talk to them that way.”- S01

Learners’ experiences with numerous teachers and styles throughout their physician training were valued by the latter example. They perceived that learners had enough knowledge and experience to provide valid and competent feedback. Additionally, they saw it as their responsibility to adjust teachings and approach the teacher-learner construct as a bidirectional relationship. This is consistent with teacher-learner relationships noted in the observation settings.

Discussion

The implications surrounding learner feedback and how physician-faculty internalize and use feedback to inform their teaching practices are substantial. In sum, physician-faculty in our study did not hold learner feedback in high regard. Extending the work identifying the issue of “source credibility” in feedback (3,11,14,20,22), a key finding that adds dimension to this concept is that physician-faculty in our study use learner feedback to adjust teaching practices based on the specific value they placed on learners’ past education experiences and competency regarding teaching skills and assessment. Results suggested that source credibility is further shaped by communication and existence of a relationship between the two parties given that study participants discussed viewing the dyad as “relationship”. Supporting a recent framework, “educational alliance” introduced by Telio and colleagues (3), this idea of a relationship implies an investment, and value in each other’s roles and contributions. The quality of the relationship and communication matters as it appears to play a role in the development of physician-faculty perceptions about their learner and by extension, receptiveness to learner feedback. If such an alliance is developed, physician-faculty could then draw more informed conclusions about learner credibility that could subsequently shape their use of learner feedback. When considering the context of resident and fellow learners, this underscores the importance of national Resident-as -Teachers programs as the intent of these programs is to build a teaching fund of knowledge for trainees. Research examining their effectiveness from the perspective of seasoned physician-faculty is needed. Additionally, future studies assessing correlations between faculty who place high value on learner feedback and credibility with increased recognition as effective teachers would greatly add to our understanding of this complex issue.

Findings also highlighted the importance of appropriate feedback metrics and mechanisms. Physician-faculty reported dissatisfaction with the metrics of the institution’s online evaluation system, and their corresponding narrative sections. They recommended rubric training for the learners to refine feedback for one-on-one teaching. Looking to our results, we support and propose a feedback rubric that is deployed via a purposeful training. To set the stage for feedback to occur as a process, rubric training could require learners to undergo brief training at their respective orientations on both the use of the rubric and importance of quality narrative feedback for program improvement and physician-faculty development. Rubric for each metric that incorporates rich descriptions could scaffold and improve the critical thinking process involved in writing constructive feedback narratives for learners. Moreover, comment boxes on evaluation reporting mechanisms with either prompts or ideal substantive comment examples could help learners’ better articulate meaningful feedback for physician-faculty and make connections with rubric scoring guides. This approach forces a reconceptualization of the role of learner feedback that is different. With the training and implementation of feedback rubric for learners, this places them in the role of teacher and expert evaluator. This alters the traditional paradigm and forces physician-faculty to expect more of learners and facilitates a system to further train learners in teaching and evaluation skills.

Finally, rubrics could include moderate tailoring to address abbreviated contact time, ensure anonymity, and review institutional safeguards against physician-faculty retaliation against the learner. A limitation of current feedback frameworks (3) is the lack of attention to how limited duration of contact time, and desire for anonymity, could impact quality communication and the establishment of a relationship. Consequently, physician-faculty being evaluated should undergo parallel training to understand context in which learners have been instructed to reflect and formatively evaluate their teaching practices given a varied set of learning/teaching conditions that consider the aforementioned obstacles. We encourage the development and testing of such tools as a next step.

Limitations

A limitation of our study is the restriction to one department and over-representation of junior faculty. Physician-faculty were not asked to disaggregate feedback by the type of learner. Differences between physician-faculty perceptions of medical students versus residents versus fellows may have emerged. Despite these limitations, findings provide critical insight into what gives rise to the receptiveness of learner feedback while providing an honest report on why physician-faculty use or disuse evaluations to inform their teaching.

Conclusion

Our study evaluates the value physician-faculty place on individual learner feedback about their teaching in the clinical setting. Despite the centrality of feedback in medical education training, physician-faculty predominantly accessed, reviewed, but disused feedback from learners to inform their teaching. This is due to the reporting mechanisms and concern over credibility of the learner; specifically, their ability to assess and recognize effective teaching skills. The introduction of feedback rubric training for learners could advance learning and contribute to sound evaluation as they are important sources of information for identifying and improving teaching and evaluation skills.35 Physician-faculty need to be able to trust and value the feedback they receive. Credible feedback shapes the decisions they make when selecting appropriate professional development opportunities, thus, shaping the quality of our medical training programs.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Karen Spear Ellinwood, PhD, JD and Gail T. Pritchard, PhD for the Academy of Medical Education Scholars (AMES) Teaching Scholars Program for providing a platform from which to design and conduct the study. We also wish to thank the faculty members who participated in this study, for their time and candor.

Declaration of Interest

No declarations of interest.

References

- Vu TR, Marriott DJ, Skeff KM, Stratos GA, Litzelman DK. Prioritizing areas for faculty development of clinical teachers by using student evaluations for evidence-based decisions. Acad Med. 1997;72(10):S7-S9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elzubeir M, Rizk D. Evaluating the quality of teaching in medical education: are we using the evidence for both formative and summative purposes? Med Teach. 2002; 24(3):313-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telio S, Ajjawi R, Regehr G. The "educational alliance" as a framework for re-conceptualizing feedback in medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):609-14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Ridder JMM, Stokking KM, McGaghie WC, Ten Cate OTJ. What is feedback in clinical education? Med Educ. 2008;42:189-97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA. 1983;250(6):777-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood BP. Feedback: A key feature and reflection: Teaching methods clinical settings. Radiology. 2000;215:17-19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements- Currently in Effect. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/429/ProgramandInstitutionalAccreditation/Common. Published July 1 , 2014. Accessed December 10, 2014.

- Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and structure of a medical school: Standards for Accreditation of Medical Education Programs Leading to the MD Degree. Available at: http://www.lcme.org/publications/functions.pdf. Published June 2013. Accessed December 10, 2014.

- Curtis DA, O'Sullivan P. Does trainee confidence influence acceptance of feedback? Med Educ. 2014;48(10):943-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arah OA, Heineman MJ, Lombarts, KM. Factors influencing residents' evaluations of clinical faculty member teaching qualities and role model status. Med Edu. 2012;46(4):381-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watling CJ, Driessen E, van der Vleuten CP, Lingard L. Learning from clinical work: The roles of learning cues and credibility judgments. Med Edu. 2012;46(2):192-200. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson P. Student perceptions of quality feedback in teacher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 2011;36(1):51-62. [CrossRef]

- Shute VJ. Focus on formative feedback. Review of Educational Research. 2008;78:153-89. [CrossRef]

- Bing-You RG, Paterson J, Levine MA. Feedback falling on deaf ears: Residents' receptivity to feedback tempered by sender credibility. Med Teach. 1997;19(1):40-4. [CrossRef]

- van der Leeuw RM, Overeem K, Arah OA, Heineman MJ, Lombarts KM. Frequency and determinants of residents' narrative feedback on the teaching performance of faculty: narratives in numbers. Acad Med. 2013;88(9):1324-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bing-You RG, Throwbridge RI. Why medical educators may be failing at feedback. JAMA. 2009;302:1330-1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein RM, Siegel DJ, Silberman J. Self-monitoring in clinical: a challenge for medical educators. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2008;28(1):5-13. [CrossRef]

- Bandura A. Self-regulation of motivation and action through goal systems In Hamilton V, Bower GH, Frijda NH, eds. Cognitive perspectives on emotion and motivation. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1988: 3-38.

- Watling CJ, Kenyon CF, Schulz V, Goldszmidt MA, Zibrowski E, Lingard L. An exploration of faculty perspectives on the in-training evaluation of residents. Acad Med. 2010;85(7):1157-62. [CrossRef]

- Sargeant J, Mann K, van der Vieuten C, Metsemakers J. Feedback falling on deaf ears: residents's receptivity to feedback tempered by sender credibility. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2008;28(1):47-54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargeant, J, Armson, H, Chesluk, B, Doran, T, Eva, K, Holmboe, E, Lockyer, J. The processes and dimensions of informed self-assessment: a conceptual model. Acad Med. 2010;85(7):1212-20. [CrossRef]

- Eva KW, Armson H, Holmboe E, Lockery J, Loney E, Mann K, Sargeant J. Factors influencing responsiveness to feedback: On the interplay between fear, confidence, and reasoning processes. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2012;17:15-26. [CrossRef]

- Thomas G. How to do your case study. Thousand Oak: SAGE Publications; 2010. Merriam SB. Case Study Research in Education: A Qualitative Approach. San Francisco: Joseey-Bass Publications; 1988.

- Merriam SB. Case Study Research in Education: A Qualitative Approach. San Francisco: Joseey-Bass Publications; 1988.

- Yin RK. Case study research: Design and method (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2003.

- Creswell JW, Miller DL. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory into Practice. 2000;39(3):124-131. [CrossRef]

- Marshall B, Cardon P, Amit P, Fontenot R. Does sample size matter in qualitative research?: A review of qualitative interviews in IS research. Journal of Computer Information Systems. 2013;54(1):11-22.

- Morrow S. Quality and Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research in Counseling Psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52(2):250-60. [CrossRef]

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1998.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park: SAGE Publications; 1985.

- Adler PA, Adler P. Observational techniques In Denzin NK, Lincoln, YS, eds. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. 377-392; 1994.

- Unluer S. Being an insider researcher while conducting case study research. Qualitative Report. 2012;17(58):1-14.

- Creswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mix method approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2009.

- Guba EG. Annual Review Paper: Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Educational Communication and Technology. 1981;29(2);75-91.

- Wolf K, Stevens E. The role of rubrics in advancing and assessing student learning. The Journal of Effective Teaching. 2007;7(1):3-14.

Reference as: Carr TF, Martinez GF. Credibility and (dis)use of feedback to inform teaching : a qualitative case study of physician-faculty perspectives. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2015;10(6):352-64. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc076-15 PDF

clinical,

clinical,  credibility,

credibility,  evaluation,

evaluation,  feedback,

feedback,  learner,

learner,  promotion,

promotion,  rubric,

rubric,  survey,

survey,  teacher,

teacher,  teaching

teaching

Reader Comments