Results of the SWJPCC Healthcare Survey

Friday, January 3, 2020 at 9:35AM

Friday, January 3, 2020 at 9:35AM Richard A. Robbins, MD

Phoenix Pulmonary and Critical Care Research and Education Foundation

Gilbert, AZ USA

Michael B. Gotway, MD

Department of Radiology

Mayo Clinic Arizona

Scottsdale, AZ USA

Julene R. Robbins, PhD, NCSP

Phoenix Pulmonary and Critical Care Research and Education Foundation

Gilbert, AZ USA

Lewis Wesselius, MD

Department of Pulmonary Medicine

Mayo Clinic Arizona

Scottsdale, AZ USA

Abstract

Debate is ongoing on how best to pay for healthcare, with a public option gaining increasing popularity. However, the Southwest US has traditionally been politically conservative and, although population demographics are rapidly shifting towards minorities, this shift is not reflected in the physician population. We conducted a voluntary, anonymous, on-line survey of the Southwest Journal of Pulmonary and Critical Care (SWJPCC) readership to determine if their attitudes differed from the public and/or nationwide surveys of physicians. The respondents, nearly all subspecialty care physicians, were universally consistent in their opinion that healthcare costs too much in the US. About two-thirds felt healthcare is a right. Administrative costs and insurance companies were viewed by most as the culprits for the high costs and hospital administrators and insurance company personnel were perceived as overpaid. Few viewed the electronic medical record as helpful in healthcare. These results seem mostly consistent with other Nationwide physician surveys.

Introduction

Most Americans continue to see healthcare costs in the U.S. as a major issue, with 79% dissatisfied with healthcare costs (1). Americans who are covered by Medicare or Medicaid are the least dissatisfied (29%), while dissatisfaction is highest among the uninsured (62%) and averages 48% among those with private insurance (2). This dissatisfaction has been reflected in the current political debates with proposals including public options such as “Medicare for All”.

Physicians have also become increasingly dissatisfied with healthcare (3). A variety of factors, such as electronic medical records, income instability and fairness, and the burden of regulations have been identified as affecting physician satisfaction and each is also affected by cost (3). Surveys have reflected this dissatisfaction but none has focused specifically on the Southwest US. The Southwest is undergoing demographic shifting, particularly in Arizona, with an increasing number of minorities, especially Latinos (4). However, this changing racial and ethnic diversity is not reflected in the Southwest physician workforce, with the vast majority remaining Caucasian, although an increasing number are now women (5).

To uncover if attitudes regarding healthcare costs differ amongst the Southwest Journal of Pulmonary and Critical Care (SWJPCC) readership, we conducted an on-line survey. The results suggest that healthcare providers agree that healthcare costs too much. Furthermore, the majority favored administrative costs/insurance expenses as the predominate contributors to the increase in costs.

Methods

Survey

An experienced survey designer (JRR) constructed a survey with the goals of determining US Southwest physician attitudes towards healthcare costs and the possible causes for the high cost. Another goal was to keep the survey brief, since previous experience was that long surveys usually have a poor response. A series of 8 questions was developed (Appendix 1).

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

Data was collected October 9, 2019 through November 27, 2019. Most results were expressed as a percentage of the responses. There were insufficient respondents between different groups (physicians, nurses, patients, etc.) to allow statistical analysis

Results

Demographics

There were 66 respondents, of which there were 61 subspecialty physicians or residents and 5 others (2 patients,1 nurse,1 technician, and 1 other). This likely reflects the readership of a pulmonary, critical care and sleep subspecialty journal such as the SWJPCC.

Healthcare Costs Too Much in the US.

There was universal agreement (all 66 respondents responding in the affirmative) that this statement is true.

Healthcare is a Right.

Forty-three of 65 responses marked this as true (66%). Twenty-two respondents felt that this statement was false (34%) and 1 with no response.

Causes for the Increase in Healthcare Costs.

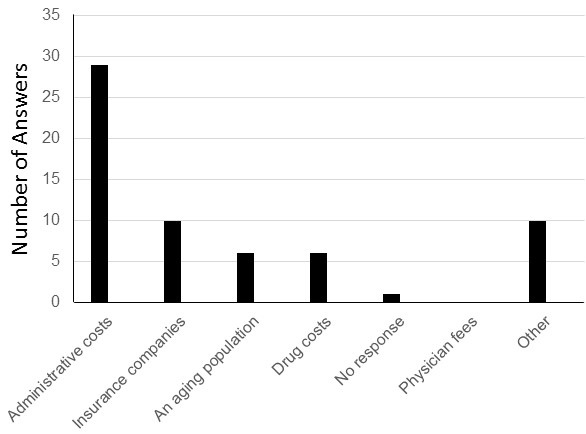

The perceived causes for the increase in healthcare costs are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Respondents answers for the causes of the increase in healthcare costs.

Although the answers somewhat differed, the majority felt that administrative costs and insurance companies were important contributors to increasing healthcare costs (39 of 62, 63%). None felt that physicians’ fees contributed to the increase in healthcare costs. Other responses are given in Appendix 2.

Which Healthcare Personnel Are Over- or Underpaid.

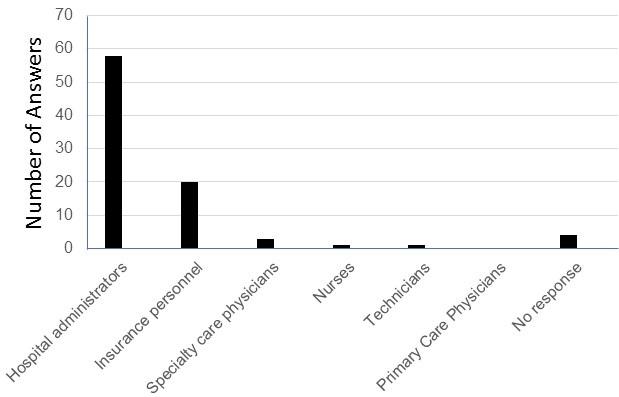

There were 87 answers as regards which personnel are overpaid. The healthcare personnel that were felt to be overpaid are show in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Respondents answers to which personnel are overpaid.

There was consensus that hospital administrators and insurance personnel were overpaid with 78 of 87 (90%) responding that they were overpaid (multiple answers could be accepted). In contrast, only 4 respondents felt specialty care physicians, and only one each, viewed nurses and technicians as being overpaid. None felt primary care physicians were overpaid.

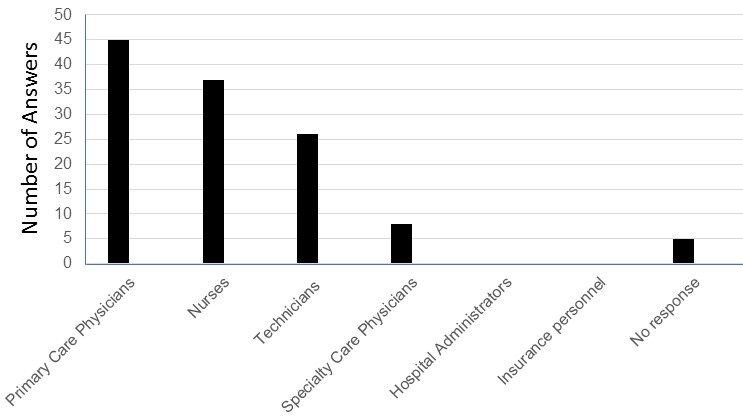

Answers to the question “which personnel are underpaid” mirrored the answers to which healthcare personnel were overpaid (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Respondents answers to which healthcare personnel are underpaid.

Forty-five of the 116 (39%) answers felt that primary care physicians were underpaid. A smaller number felt nurses (37 responses, 32%), technicians (26 responses, 22%), and specialty care physicians (8 responses, 7%) were underpaid. None felt that hospital administrators or insurance personnel were underpaid.

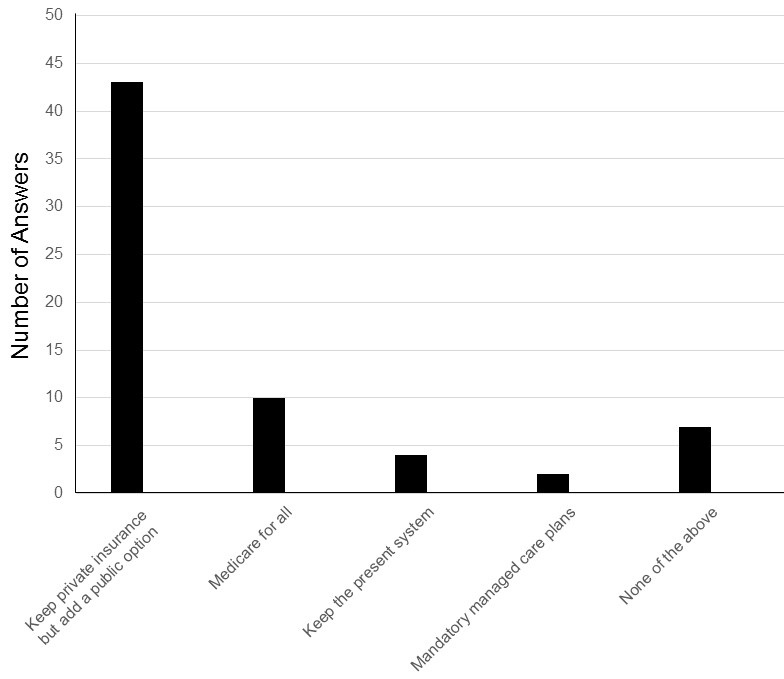

Method for Healthcare Payment

Most (65%) favored keeping private insurance but adding a public option or “Medicare for All” (15%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Responses to how to pay for healthcare.

Only 4 (6%) favored keeping the present system and only 2 (3%) favored mandatory managed care plans.

Innovations that Have Improved Quality in Healthcare

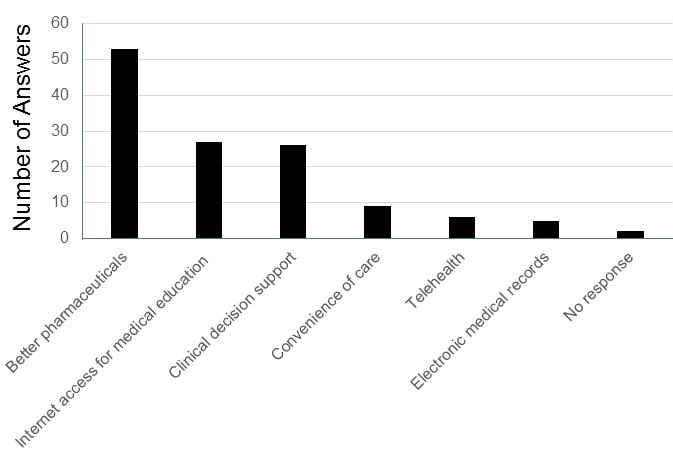

Innovations that were felt to improve healthcare are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Innovations that have improved healthcare.

Nearly half of the 126 responses (53 responses, 42%) felt better pharmaceuticals had improved healthcare. Many also felt that internet access for medical education, such as looking up specific questions, on-line education (27 responses, 21%), and clinical decision support (26 responses, 21%) had helped. Interestingly, the most widespread innovation in healthcare in the past few years- electronic medical records- received the least support with only 5 positive responses (4%).

Discussion

This survey of readers of the Southwest Journal of Pulmonary and Critical Care strongly reflects the concern that healthcare costs too much in the US. About two-thirds of respondents felt healthcare is a right. Administrative costs and insurance companies were viewed by many as the reasons for the high costs with hospital administrators and insurance company personnel viewed as overpaid. Few viewed the electronic medical record as helpful in healthcare.

The physician opinion that healthcare costs too much is consistent with the US paying the highest cost for healthcare in the world, at over $10,000 per capita in 2017 (6). The concept that administrative costs account for much of these higher costs has only recently become widely accepted. This late realization is despite rising administrative costs highlighted by multiple articles from Woolhandler and Himmelstein, beginning with a 1991 article in the New England Journal of Medicine (7). They referred to medicine as “a spectator sport” with doctors, patients, and nurses performing before an enlarging audience of utilization reviewers, efficiency experts, and cost managers. Many physicians have watched in horror as the trend pointed out by these authors nearly 30 years ago has steadily worsened. Reports of ultrahigh CEO salaries have recently drawn some attention in both the medical and popular literature accenting the high administrative costs (8,9).

The high costs of healthcare have led to an increasing number of patients and physicians supporting a public option. Previously, physician groups, such as the American Medical Association (AMA), have thwarted public health insurance proposals since the 1930s. However, as the next generation of physicians takes on leadership roles, even groups such as the AMA are now reexamining this question (10). A March 2018 New England Journal of Medicine survey found 61 percent of 607 respondents said single-payer would make it easier to deliver cost-effective, quality health care (11). This is similar to the 80% of our readership favoring a public option. However, in our survey, most (65%) favored keeping private insurance in addition to the public option. This likely represents a physician reaction to increasing regulatory burdens by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Department Veterans of Affairs, two US government agencies involved in healthcare.

Despite the changing population demographics in the Southwest US, physicians still tend to be Caucasian, although more are now women (4,5). Our data suggests that support for a public option is high among physicians. We did not ask our readers their age, although younger physicians preferentially seem to be more likely to support a public option (10). Furthermore, most pulmonary physicians are now Democrats who tend to support a public option (12). We also did not ask where the physicians practice, although it seems likely most are in the Southwest US.

Our data are consistent with other surveys, although the Southwest US and the Southern US are often viewed as the home of US conservatism. However, even though most favored a public option in our survey, there seems to be sufficient distrust of “big government” to limit the choice to only a public option (13).

References

- Jones JM, Reinhart RJ. Americans remain dissatisfied with healthcare costs. Gallup Poll. Nov 28, 2018. Available at: https://news.gallup.com/poll/245054/americans-remain-dissatisfied-healthcare-costs.aspx (accessed 12/17/19).

- Saad L. Four in 10 in U.S. dissatisfied with their healthcare costs. Gallup Poll. Dec 12, 2016. Available at: https://news.gallup.com/poll/199298/four-dissatisfied-healthcare-costs.aspx (accessed 12/17/19).

- Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. Rand Health Q. 2014 Dec 1;3(4):1. eCollection 2014 Winter.

- Cárdenas V, Kerby S, Wilf R. Arizona’s demographic changes. Center for American Progress. 2012. Available at: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/poverty/news/2012/02/28/11060/arizonas-demographic-changes/ (Accessed 12/17/19).

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA. The racial and ethnic composition and distribution of primary care physicians. J Healthcare Poor Underserved. 2018;29(1):556-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer B, Cox C. How does health spending in the U.S. compare to other countries? Peterson KFF Health System Tracker. December 7, 2018. Available at: https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/health-spending-u-s-compare-countries/#item-start (accessed 12/17/19).

- Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU. The deteriorating administrative efficiency of the US healthcare system. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(18):1253-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins RA. CEO compensation-one reason healthcare costs so much. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2019;19(2):76-8. [CrossRef]

- Andrzejewski A. Top U.S. "Non-Profit" hospitals & CEOs are racking up huge profits. Jun 26, 2019. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/adamandrzejewski/2019/06/26/top-u-s-non-profit-hospitals-ceos-are-racking-up-huge-profits/#48c7a4d119df (accessed 12/17/19).

- Luthra S. Once its greatest foes, doctors are embracing single-payer. Kaiser Health News. August 7, 2018. Available at: https://khn.org/news/once-its-greatest-foes-doctors-are-embracing-single-payer/ (accessed 12/17/19).

- Serafini M. Why clinicians support single-payer-and who will win and lose. NEJM Catalyst. January 17, 2018. Available at: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.18.0278 (accessed 12/17/19).

- Frellick M. Physician specialties correlate with political affiliation. Medscape. October 12, 2016. Available at: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/870192 (accessed 12/17/19).

- Robbins RA, Wang AC. Medicare for all-good idea or political death? Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2019;19(1):18-20. [CrossRef]

Cite as: Robbins RA, Gotway MB, Robbins JR, Wesselius LJ. Results of the SWJPCC healthcare survey. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2020;20(1):9-15. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc074-19 PDF