Profiles in Medical Courage: Joseph Goldberger, the Sharecropper’s Plague, Science and Prejudice

Friday, June 8, 2012 at 10:26AM

Friday, June 8, 2012 at 10:26AM “You must accept the truth from whatever source it comes”. -Maimonides

The Sharecropper’s Plague

In the early half of the twentieth century a mysterious disease, “the sharecropper’s plague”, reached epidemic proportions in the Southern US (1). Each state decided whether it would recognize and publicly admit the existence of what was then considered an embarrassment. The total number of new annual cases was estimated as about 75,000 in 1915 and about 100,000 throughout the 1920s (2). The disease had a 40% mortality rate, and many survivors with dementia were confined to mental institutions (3). Patients initially presented with symmetrically reddened skin, similar to that produced by a sunburn or poison oak. Later, the dermatitis turned rough and scaly in one or more locations, such as the hands, the tops of the feet, or the ankles, or in a butterfly-shaped distribution across the nose. Disturbances of the digestive tract and the nervous system occurred as late manifestations. This led to the plague being characterized by 4 D’s: dermatitis, diarrhea, dementia and death. In case you have not guessed, the “sharecropper’s plague” was pellagra.

“Pellagraphobia" developed as the disease acquired a social stigma that left victims and their families ostracized (4). Many hospitals refused admittance to patients with pellagra and many staff refused to care for them. Quarantine was common and elementary schools tried to bar children whose family members had pellagra (5). The cause of the disease was unknown. A number of etiologies were proposed including infection; the eating of moldy corn; inherited susceptibility; heavy exposure to sunlight; and exposure to cottonseed oil (2). There were more than 200 proposed "cures" for pellagra included diet, arsenic, castor oil, quinine, strychnine, and the healing waters of mineral springs (5).

In response the US Surgeon General, Walter Wyman, appointed a seven-man commission headed by Dr. Claude H. Lavinder to find the etiologic agent and perhaps identify an insect vector. Lavinder toured affected areas and established a small laboratory at the South Carolina Hospital for the Insane where he injected rabbits, chickens, and guinea pigs with blood, spinal fluid, and spleen pulp from fatal cases of pellagra, without results. In 1911, he set up a larger laboratory at the Marine Hospital in Savannah and unsuccessfully attempted to transmit the causative agent to monkeys. The Commission conducted a survey of pellagra cases in the cotton mill districts in South Carolina where it was especially common. In its 1914 report, the commission concluded that pellagra had no relation to diet, that it spread most rapidly where sanitary disposal of waste was poorest, and that the disease occurred almost exclusively in people who lived in or next to the house of another person with pellagra (6). The general consensus was that pellagra was likely infectious. These conclusions are not surprising since the early twentieth century was an era when infections were being discovered as the causes of many diseases such as yellow fever, dengue fever, typhus, typhoid fever, lobar pneumonia, tuberculosis, cerebrospinal meningitis, syphilis, cholera, malaria, dysentery, scarlet fever, tetanus, and diphtheria. Pellagra was viewed as just another of those diseases with an as yet undiscovered pathogen.

Goldberger’s Investigations

Human Observations and Dietary Interventions

When Lavinder asked to be reassigned in 1914, he was replaced by Joseph Goldberger.

Figure 1. Dr. Joseph Goldberger

Goldberger spent his first 3 weeks in the South, directly observing patients with pellagra and their living environment. He summarized his observations with a report and hypothesis (8). He stated that pellagra was: 1) present almost exclusively in rural areas; 2) associated with poverty; 3) associated with a relatively cheap and filling diet consisting of the "three M's", meat (fatback), meal (corn meal), and molasses; and 4) not acquired by nurses, attendants, or employees in hospitals or orphanages whose inpatients had the disease. The last finding seemed particularly incompatible with an infectious cause. Goldberger hypothesized that the staff's peculiar exemption from or immunity to the disease could be explained by a difference in diet.

To prove his hypothesis, Goldberger tried to prevent and cure pellagra by dietary interventions. In two orphanages having high rates of endemic pellagra he identified 172 patients with pellagra and 168 children who were initially free of disease (8). He arranged for both groups of to receive a new, more varied diet, subsidized by Federal funds. The results were evident in just a few weeks: No new cases of pellagra occurred and almost all children with pellagra were cured. After a year, the two orphanages had only one case of recurrent pellagra.

Goldberger then repeated the study in a mental asylum, using a randomized, controlled trial (9). Of 72 patients with pellagra, all were cured after the introduction of the new diet. The treatment group had a high drop-out rate, however, because some patients' mental status improved so greatly that they were permitted to leave the asylum. In the group on the old diet, the recurrence rate of pellagra was almost 50%. Interestingly, when the Federal subsidies expired at the end of these studies, the diets returned to the old three M's diet and 40% of the inmates again developed pellagra.

Goldberger then began a new study to induce pellagra by dietary deprivation (10). In a prison where pellagra had never been reported, a dozen volunteers were promised full pardons at the experiment's end for eating an experimental diet. The diet consisted largely of cereal and included biscuits, gravy, cornbread, grits, rice, syrup, collard greens, and yams. By the end of the 9 month study, 7 of the 12 inmates were diagnosed with pellagra. In all instances, resumption of a better diet resulted in cure.

To refute the theory that pellagra was infectious, Goldberger injected blood from patients with pellagra into the deltoids of healthy volunteers, including himself and his wife (11). He also mixed extracts of skin parings, nasal secretions, urine, and feces from patients with pellagra into a wheat dough concoction that was swallowed by all volunteers. These "filth party" experiments were repeated seven times. No signs of pellagra developed in the volunteers.

Demographic Studies

Goldberger next studied the basic demographics, socioeconomic status, and diet of patients with pellagra (12,13). In these surveys, Goldberger found that a poor year in cotton production was usually followed by an increase pellagra mortality (13). He showed an inverse relationship between socioeconomic status and the incidence of pellagra. Goldberger also found a significant correlation between the rise and fall in the price of animal protein foods and the disease's onset and remission (12,13). These data further supported his hypothesis that pellagra was caused by a dietary deficiency.

Laboratory Studies

Goldberger hypothesized that pellagra was caused by an amino acid deficiency, possibly tryptophan, based on his demographic and human studies. Goldberger soon realized that ordinary yeast contained and was the most potent source of the pellagra-preventive factor in rats and in dogs (14). In 1927 he arranged to have the Red Cross ship large quantities of yeast into flood-stricken areas along the Mississippi river (15). The expected outbreak of pellagra did not occur; instead, the disease fell below its usual seasonal incidence. After the emergency, yeast was no longer provided, and the usual level of pellagra returned to the area. Goldberger died in 1929 before he could find a specific pellagra cure.

In 1937 nicotinic acid or niacin was found to cure pellagra in dogs (16). This finding was soon confirmed for human pellagra (17). The final, almost complete elimination of pellagra dates to the 1940s coinciding with improvements in diet and a requirement by many states to enrich food with vitamins including niacin (18). What provoked the epidemic at the beginning of the twentieth century is not entirely clear. However, changes in the methods of milling corn may have led to the outbreak, because the germ or embryo in the corn kernel is removed in the new milling process begun at the turn of the century. The kernel contains a high proportion of lipid, enzymes, and cofactors, including nicotinic acid (19).

Politics and Pellagra

Goldberger investigations are exceptional. He performed community observation, clinical investigation, and laboratory investigations that led to the elimination of a common health problem. Yet, his extraordinary accomplishments are largely unrecognized. Politics and prejudice seem to be largely responsible for Goldberger’s obscurity.

Politics apparently had great influence on pellagra public policy. An association of pellagra with poverty was clear, and offended Southern pride where the disease was concentrated. When the epidemiologic studies of Goldberger, a Northerner, an immigrant, and a Jew pointed to social and economic factors as being responsible for the occurrence of pellagra, Southern sensitivities were further riled. Editorial pages and speeches by congressmen criticized and condemned such insulting inferences concerning the contentment of the people of the South (2).

When a letter from Goldberger to the Surgeon General describing the extent of pellagra and its relationship to poverty and poor diet reached the press; it stimulated the newly inaugurated president, Warren Harding, to write the Surgeon General asking for a complete report. Harding suggested that the Red Cross provide aid, and offered to ask for a congressional appropriation (2). This infuriated a number of influential Southern politicians including Congressman James F. Byrnes (later U.S. Senator, Secretary of State, and Supreme Court Justice). He called the news reports of "famine and plague" in South Carolina an "utter absurdity," calling for rejection of offers of aid from the Red Cross. A Georgia city wired one of their senators, Tom Watson, "When this part of Georgia suffers from famine, the rest of the world will be dead!" (20). The United Daughters of the Confederacy at first voted to thank President Harding for his concern, but a month later it sent him a letter of protest. "Famine does not exist anywhere in the South," their letter stated, "and we fail to find a general increase in pellagra" (20). Since pellagra was common in Italy, Italian immigrants were blamed for the outbreak of the disease (2). No one seemed to notice that the Italians living in the South did not have pellagra, since they did not favor the meat, meal and molasses diet that led to the disease.

Goldberger’s Legacy

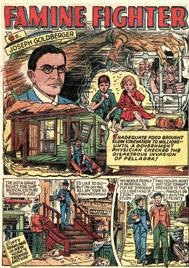

Goldberger died in 1929 of renal cell carcinoma not having convinced public health officials of a dietary cause of pellagra. Goldberger should be remembered not only for his superb investigations but for formulating a hypothesis, testing it and not surrendering to insults of his heritage or religion. Although rarely remembered in medical textbooks, he has been immortalized in some unlikely places including “Real Life Comics” in 1941 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Joseph Goldberger in “Real Life Comics”.

Figure 2. Joseph Goldberger in “Real Life Comics”.

Figure 2. Joseph Goldberger in “Real Life Comics”.

In some aspects Goldberger’s story is echoed in modern day politics where politicians attempt to manipulate or deny scientific discovery to further their own political careers. Even when Goldberger showed that affordable therapy with yeast cured pellagra, many Southern politicians remained reticent to accept diet as a cause of the disease. Their ambitions undoubtedly contributed to the excess mortality and morbidity of thousands of impoverished Southerners in the early twentieth century.

References

- Elmore JG, Feinstein AR. Joseph Goldberger: An unsung hero of American clinical epidemiology. Ann Intern Med 1994;121:372-37.

- Bollet AJ. Politics and pellagra: the epidemic of pellagra in the U.S. in the early twentieth century. Yale J Biol Med 1992;65:211-21.

- Lavinder CH. The prevalence and geographic distribution of pellagra in the United States. Public Health Rep 1912;27:2076-88.

- Niles GM. Pellagraphobia: A word of caution. JAMA 1912;58:1341.

- Etheridge EW. The Butterfly Caste: A Social History of Pellagra in the South. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Company; 1972.

- Siler JF, Garrison PE, MacNeal WJ. Pellagra, a summary of the first progress report of the Thompson-McFadden Pellagra Commission. JAMA 1914;62:8-12.

- Parsons RP (1943). Trail to light: A biography of Joseph Goldberger. Bobbs-Merrill. ASIN B0007DYTFM.

- Goldberger J. The etiology of pellagra: The significance of certain epidemiological observations with respect thereto. Public Health Rep1914;29:1683-86.

- Goldberger J, Waring CH, Tanner WF. Pellagra prevention by diet among institutional inmates. Public Health Rep 1923;38:2361-68.

- Goldberger J, Wheeler GA. The experimental production of pellagra in human subjects by means of diet. Hygienic Laboratory Bulletin 1920;120:7-116.

- Goldberger J. The transmissibility of pellagra: Experimental attempts at transmission to human subjects. Public Health Rep. 1916;31:3159-73.

- Goldberger J, Wheeler GA, Sydenstricker E. A study of the diet of nonpellagrin and of pellagrin households. JAMA 1918;71:944-9.

- Sydenstricker E, Wheeler GA, Goldberger J. Disabling sickness among the population of seven cotton-mill villages of South Carolina in relation to family income. Public Health Rep. 1918;33:2038-51.

- Goldberger JG, Wheeler GA, Lillie RD, Rogers LM. A further study of butter, fresh beef and yeast as pellagra preventives, with consideration of the relation of factor P-P of pellagra (and black tongue of dogs) to vitamin B. Public Health Rep 1926;41:297-318.

- Goldberger JG, Sydenstricker E. Pellagra in the Mississippi flood area. Public Health Rep 1927;42:2706-25.

- Elvehjem CA, Madden RJ, Strong FM, Wooley DW. Relation of nicotinic acid and nicotinic acid amide to canine black tongue. J Amer Chem Soc 1937;59:1767.

- Smith DF, Ruffin JM, Smith SG. Pellagra successfully treated with nicotinic acid: a case report. JAMA 1937;109:2054-5.

- Wilder RM. A brief history of the enrichment of bread and flour. JAMA 1956;162:1539-40.

- Carpenter KJ. Effects of different methods of processing maize on its pellagragenic activity. Fed Proc 1981;40:1531-5.

- Etheridge EW: The Butterfly Caste. A Social History of Pellagra in the South. Westport, CT, Greenwood Press, 1972, 278 pp