Profiles in Medical Courage: Thomas Kummet and the Courage to Fight Bureaucracy

Saturday, January 12, 2013 at 10:56AM

Saturday, January 12, 2013 at 10:56AM “You can’t fight city hall”-Unknown.

Abstract

Thomas Kummet was an oncologist wrongly accused in his mind of delivering substandard care. His fight for correcting what he believed to be a mistake illustrates the difficulty physicians face when challenging the current peer review system. In an attempt to defend his reputation he filed suit which was eventually dismissed by a Federal Court. His frustration over the futility of his fight is illustrative of the difficulties many physicians have faced in fighting a large bureaucracy and an unsympathetic justice system.

Introduction

Thomas Kummet (Figure 1) was an oncologist at the Phoenix Veterans Administration (VA) Medical Center.

Figure 1. Dr. Thomas Kummet

He had been chief of oncology/hematology for nearly 20 years and was well-respected by his colleagues, staff and students. He was regarded as an excellent clinician. During his 20 years at the VA he no law suits or adverse actions. While attending on general medicine, the deaths of two patients launched a series of events leading Dr. Kummet to eventually file suit against the VA.

Case Presentations

Case 1

A 72 year old male patient was admitted to the surgical critical care (SICU) unit after being found comatose on the surgical ward. He had undergone surgery for peripheral vascular disease 3 days earlier, but the resident physician failed to order monitoring of his warfarin therapy. At the time of the transfer, his prothrombin time was markedly elevated and a cat scan showed a large intracranial hemorrhage. The surgery resident stated to the family that the diagnosis was disseminated intravascular coagulation as a complication of the surgery. Shortly after transfer to the SICU the patient expired. The attending intensivist, a medical internist informed the family of the true cause of the bleeding which led to the patient’s death. The family sued, and received a settlement before trial.

In accordance with hospital policy, the chart was sent to the surgery service for review. The surgery service selected the intensivist as being responsible, who learned of that action only much later, when the state of Arizona began an investigation and placed the intensivist’s name on its public website as a physician guilty of malpractice.

Case 2

JV was a 67-year-old man who was admitted from dialysis clinic to the Internal Medicine Service in August 1999 with a history of non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, end stage renal disease with dialysis, hypertension, anemia of chronic disease, and chronic ulcerations of the feet. He had developed progressive ascites for several weeks, and had been feeling weak and tired. JV was admitted with a systolic blood pressure of 87 mm Hg, a WBC count of 20,000 cells/mm3, and fever. A medical workup was begun to find the source of a possible sepsis syndrome. The vascular surgery service was consulted with regard to a wound on the patient's left arm which had been the result of an attempted placement for a dialysis access which had failed to mature. The patient was evaluated and found to have a seroma which was subsequently drained without any complications. During follow up, it was noted that the patient had a gangrenous left foot with non-reconstructible peripheral vascular disease. Subsequently a below the knee guillotine amputation was performed.

However, JV continued to have intermittent hypotension and fever. In addition to broad spectrum antibiotics he was receiving enoxaparin 30 mg daily as DVT prophylaxis. On the first postoperative day the consulting intensivist recommended a thoracentesis of a left pleural effusion followed by a paracentesis to exclude these as a source of infection. The thoracentesis and paracentesis were performed without incident. Approximately 2 liters of clear ascitic fluid was removed from the right upper quadrant. About 2 hours after the procedure, the patient experienced the acute onset of abdominal pain, a sudden decrease in blood pressure, a rigid abdomen, apnea and a Code Arrest was called. He was successfully resuscitated. His hemoglobin was noted to have decreased from 11 to 7.9 gm/dl.

JV was taken emergently to the operating room where a damage control laparotomy was initiated and a massive hemoperitoneum was noted. This was evacuated and a vessel on the right upper abdominal wall was identified and ligated. During the exploration it was noted that while the cirrhotic liver was unmarked, but the stomach had a 1 cm perforated ulcer in the anterior wall which was bleeding briskly. This was oversewn and then patched with omentum. During the resuscitation, he received seven units of red blood cells, seven units of fresh frozen plasma, and multiple infusions of crystalloids and colloid solutions in an attempt to maintain blood pressure. A Swan-Ganz pulmonary artery catheter was inserted and fluid resuscitation was guided by pulmonary artery catheter indices. After adequate fluid resuscitation, he remained hypotensive with a low cardiac index and was supported with a combination of vasopressor agents and inotropes including super maximal doses of dobutamine, dopamine, phenylephrine and norepinephrine. However, he remained hypotensive, and with the family at his bedside and after a detailed discussion, the family elected to cease support. The patient died shortly afterwards.

Pertinent Laboratory

His creatinine was 3.2 mg/dL and his blood urea nitrogen was 37 mg/dL. Both his pleural fluid and ascitic fluid were exudative. Blood cultures and peritoneal cultures were all negative. His prothrombin time at the time of his paracentesis was slightly elevated at 13.8 seconds (upper limits of normal 13.3) but partial thromboplastin time and platelet count were within normal limits.

Hospital Course and Surgical Review

When the surgical team was contacted regarding the sudden drop in blood pressure and rigid abdomen, they accused the medicine team of “puncturing” the patient’s liver by the paracentesis with the family present. The family then confronted the resident and intern who performed the paracentesis for this “screw up”. Relevant is that this surgical team is the same that had recently been responsible for the events in case one.

Since the patient expired on the surgical service, the chart in case 2 was again sent to the surgical service to assess attending responsibility. The medical attending at the time of the patient’s initial admission was selected as the responsible physician, again without any knowledge or input from that medical attending.

JV’s family had hired an attorney who hired a nephrologist in private practice from Tarzana, CA to review the case. The physician opined that the paracentesis should not have been performed because of an excess bleeding risk and the patient died as a result of the paracentesis. The physician did not mention the perforated gastric ulcer which was bleeding “briskly” at the time of the operation. A local peer review was conducted and concluded that bleeding was almost certainly from the perforated gastric ulcer and had nothing to do with the paracentesis.

The US Attorney’s Office obtained additional expert opinions from outside the VA who concluded there was no merit to the case and all applicable standards of care were met. Despite these reviews, the US Attorney’s Office settled the case for $250,000. The reason for the decision to settle the case remains unclear.

Local VA Actions

The attending physicians discussed of both cases with the Risk Manager at the Phoenix VA, who dismissed concerns by saying that the hospital needed to maintain its hard-to-recruit-and-retain surgery staff, but that the medical physicians who had been with the hospital for 20 years were less likely to leave. In addition, the hospital risk manager assured the medical service physicians that the hospital would not report them to the National Practitioner Data Bank, as no one felt they were responsible for malpractice.

New VA regulations were in effect when Case 2 was settled. Thomas Kummet was the internal medicine attending who was informed by the hospital of the matter for the first time when he was told he had ten days to respond to VA headquarters about the “malpractice” case, and according to the regulations he was entitled to supervised review of the chart and the settlement documents. However, while he was allowed to see the chart, there were no documents to explain the lawsuit or the rationale for settlement. When the Risk Manager was asked for those documents, it was acknowledged that they would not be provided, no matter what VA regulations stated, as the US Attorney’s office refused to provide them to the hospital. Again Dr. Kummet was assured that the VA did not report physicians to the National Practitioner Data Bank in circumstances where there was no malpractice.

Three VA reviewers found no evidence of malpractice in the management of this patient. However, Dr. Kummet was informed he was being reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank and the State of Arizona as being responsible for a malpractice settlement.

Actions by the State of Arizona Board of Medical Examiners (BOMEX)

After being notified of the NPDB placement, the state BOMEX began their own investigation of Dr. Kummet, after first placing notification on their public website that he and the intensivist in Case 1 were responsible for malpractice. This prompted patients to begin to ask for details of his “multiple” errors, to be referred to other physicians, and of why he was still allowed to practice. BOMEX asked Dr. Kummet for the medical records, which the local VA refused to provide, claiming Federal law precluded release. When the state responded that Dr. Kummet’s (only) medical license was therefore at risk, Dr. Kummet hired legal representation. With that assistance, the hospital sent a copy of the patient’s chart to the BOMEX.

The state investigation was subsequently completed, no action was taken except to remove the notation on the website that a case was under investigation, and a request by the doctor for the documents of the state’s investigation was denied by BOMEX.

VA Headquarters Actions

The Veterans Administration had come under criticism in the early 2000’s because only 37% of physicians involved in a malpractice settlement were reported to the National Practioner Data Bank (NPDB). The VA initiated a peer review process and began reporting all practioners whose care was judged as substandard to the NPDB. This included some instances of previously settled claims such as Dr. Kummet’s. This new policy was designed to report all physicians because, as it was explained to the local Risk Manager, “it is good for the VA to show that we are tough on physicians.”

After the case was settled, it was referred to John Grippi MD from the Buffalo VA who was heading the VA’s peer review. He referred the case to a non-VA panel consisting of Edmond Gicewicz MD, a retired general surgeon; Norbert Kuberka MD, a retired oncologist; and Gregory Czajka PA, a surgical assistant. The panel concluded that “technical errors in the performance of abdominal paracentesis resulted in significant intra-abdominal hemorrhage”.

Dr. Kummet’s name was submitted to the National Practioner Data Bank, 10 days after he was first informed of the claim settlement and 4 years after the patient’s death.

Legal Action

Dr. Kummet obtained legal counsel and suit was filed in Federal court since the VA is a Federal agency. The suit failed, however, as there is no statutory or case law that required the local institution to follow its own procedures, or to allow physicians due process claims in these matters.

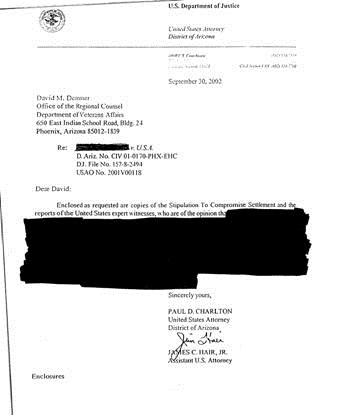

The legal proceedings were unsuccessful at obtaining any documents to support the decision to report to the NPDB, only to be told what was done was legal and in the VA’s best interest. The US Attorney’s office responded to a Freedom of Information Act request by supplying one nearly totally redacted document and claimed everything else was protected attorney work product (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Redacted letter from US Attorney’s Office.

Conclusion

Subsequently, Dr. Kummet left the VA system and is in private practice in Washington State. There are multiple instances where hospitals have retaliated against physicians for financial gain or for reporting substandard care (1). However, this does appear to be applicable in this case. If you, the reader, concludes from the case presentation that Dr. Kummet delivered substandard care, then he was justifiably punished.

On the other hand, if you agree the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases that a abdominal paracentesis should be performed in patients with new-onset ascites (2) and that the patient’s intraperitoneal hemorrhage resulted from the perforated gastric ulcer rather than the paracentesis, then you likely agree with Dr. Kummet that he was falsely accused by the VA’s peer review system.

Dr. Kummel’s experience illustrates that physicians face a hospital peer review and justice system that fails to grant the basic rights to those accused of professional misconduct that it grants to those accused of criminal behavior. These include the right to a speedy and public trial by an impartial jury; to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor; and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense. Furthermore, the decision to settle the lawsuit that negatively impacted Dr. Kummet were made by attorneys without the background or knowledge to know if substandard care was delivered.

Regardless, Dr. Kummet should be admired for his courage in fighting what he views as unfair accusations by those more concerned with political perceptions than improvement in healthcare and a legal system unconcerned with slandering his reputation.

Richard A. Robbins, MD*

References

- Kinney ED. Hospital peer review of physicians: does statutory immunity increase risk of unwarranted professional injury? MSU Journal of Medicine and Law 2009;57:57-89.

- Runyon BL. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: An update. Hepatology 2009;49:2087–107.

*Dr. Thomas Kummet assisted in the preparation of this manuscript.

Reference as: Robbins RA. Profiles in medical courage: Thomas Kummet and the courage to fight burearcracy. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2013;6(1):29-35. PDF