Finding a Mentor: The Complete Examination of an Online Academic Matchmaking Tool for Physician-Faculty

Monday, December 8, 2014 at 8:47AM

Monday, December 8, 2014 at 8:47AM Guadalupe F. Martinez, PhD1

Jeffery Lisse, MD1

Karen Spear-Ellinwood, PhD, JD2

Mindy Fain, MD1

Tejo Vemulapalli, MD1

Harold Szerlip, MD3

Kenneth S. Knox, MD1

1Departments of Medicine and 2Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

3Department of Medicine, University of North Texas Health Science Center Department of Medicine, Fort Worth, TX

Abstract

Background: To have a successful career in academic medicine, finding a mentor is critical for physician-faculty. However, finding the most appropriate mentor can be challenging for junior faculty. As identifying a mentor pool and improving the search process are paramount to both a mentoring program’s success, and the academic medical community, innovative methods that optimize mentees’ searches are needed. This cross-sectional study examines the search and match process for just over 60 junior physician-faculty mentees participating in a department-based junior faculty mentoring program. To extend beyond traditional approaches to connect new faculty with mentors, we implement and examine an online matchmaking technology that aids their search and match process.

Methods: We describe the software used and events leading to implementation. A concurrent mixed method design was applied wherein quantitative and qualitative data, collected via e-surveys, provide a comprehensive analysis of primary usage patterns, decision making, and participants’ satisfaction with the approach.

Results: Mentees reported using the software to primarily search for potential mentors in and out of their department, followed by negotiating their primary mentor selection with their division chief’s recommendations with those of the software, and finally, using online recommendations for self-matching as appropriate. Mentees found the online service to be user-friendly while allowing for a non-threatening introduction to busy senior mentors.

Conclusions: Our approach is a step toward examining the use of technology in the search and match process for junior physician-faculty. Findings underscore the complexity of the search and match process.

Introduction

Across the spectrum of disciplines within the academy, it is well documented that mentorship is key to career advancement and satisfaction among faculty (1). For physician-faculty, mentoring is “considered to be a core component of the faculty duties…to fulfill…th(e) academic medicine mission” (2). Although important, structural barriers to mentorship still exist (2,3). Finding an appropriate mentor is critical not only in establishing a productive and engaging mentorship, but in having a successful career in academic medicine (4). However, scholars note that finding the most appropriate person is not without its challenges: especially for junior faculty (3-7,9). Some studies find that junior faculty (and faculty new to institutions) depict the search process as the most difficult step in establishing a mentorship (3,7,9,10). In these studies, mentees recommend a match process that begins with a comprehensive list of potential mentors that includes contact information (3,7). Although noteworthy, this recommendation fails to elaborate on the extent to which a mere list could improve the search and match process. How such lists are implemented or if supplemental mechanisms were used to connect unfamiliar faculty is unclear.

Prior literature stresses the importance of “effort and persistence” when embarking on a search (3,4,9). Through this seemingly daunting process, scholars specifically advise mentees to ask colleagues to connect them to others with similar interests, and invest time into researching the backgrounds of potential mentors to determine their suitability. However, there are inherent challenges to this approach. First, the time spent investigating mentor backgrounds may vary greatly depending on the number and quality of resources available to conduct such an investigation. Second, mentees new to an institution could find it difficult and/or unproductive to ask new colleagues to connect them to potential mentors as colleagues may not be able to make an appropriate connection if they are unfamiliar with the mentor pool. Although this could point mentees in the right direction, they could spend an inordinate amount of time meeting with numerous contacts only to find academic and clinical interests to be unrelated or tangentially related to theirs. Previous studies found that mentees who self-match with a mentor, are more likely to be satisfied with their mentorship experience (3,4,7,8). Yet, if the institutional mentoring culture functions as described above, mentees would have to rely solely on their division chief or department chair for an assigned mentor. This could be problematic if the chief or chair is unfamiliar with the strengths of the mentor pool.

In hallmark studies by Williams et al. (7), and Straus et al. (3), they highlight perceived barriers to mentorship from the mentee perspective, and find those to be: a) a lack of local and adequate mentor selection, b) time constraints for the mentors, c) inadequate access, and d) a lack of formal programs and mechanisms to connect faculty. Straus et al.’s (3) study also sheds light on mentees desire to choose a mentor instead of being assigned. They find that mentees perceive assigned partnerships as superficial, but that assigned matches are sometimes useful because the search process is challenging for those new to an institution. Given the conflicting perceptions, these authors call for additional strategies to improve the search and match process as well as an examination of those strategies. Methods to optimize mentees’ time and diversify searches have yet to be delineated. More importantly, the role technology could play in mentoring remains understudied. As identifying the mentor pool and improving the search process are paramount to both, a mentoring program’s success, and the academic medical community, innovative approaches are needed.

We build on the work of Straus et al. (3), and Sambunjak et al. (10) by examining the search and match process for physician-faculty mentees participating in our department-based mentoring program. In our cross-sectional study we seek to better understand internal matching behaviors and the role technology could play. We detail and explore technology aimed at improving the search and match process for our mentees. This “matching” tool further advances our knowledge about the role technology could (or could not) play in addressing the challenges associated with the search and match process. Our research questions ask: If a “matching” tool is implemented, what would the matching behavior be within the department? What are the primary usage patterns among mentees? How receptive have mentees been in adopting this mechanism to aid their search and matching efforts?

Methods

The University of Arizona’s Department of Medicine developed a department-based faculty mentoring program in March 2011 during which a needs assessment was conducted on junior physician-faculty. First, like Straus et al.’s (3) findings, mentees partaking in our needs assessment desired assistance with the search and match process. Mentees reported a lack of knowledge about available mentors, their areas of expertise, and difficulty establishing contact with senior faculty. The committee concluded experimenting with a computer program that functioned much like an online matchmaking service would improve the process; extending matching beyond the common strategies of contact list distribution, top down assignments, and informal social forums. The committee then customized an online matchmaking program, Mentor Match© (Intrafinity Inc., Ontario), to create a “virtual space” for mentor and mentee use. The committee crafted a “one-stop shop” where faculty accessed mentor/ mentee profiles containing academic interests, department mentoring events, and mentorship contract templates (Figure 1).

Figure 1. University of Arizona department of medicine opening user console view.

It was suspected that our faculty demographics included an overrepresentation of junior faculty (assistant professor rank) as compared with the number of senior faculty (associate and full professor rank) (11,12). Also evident was that commitments to medical students and trainees prevented senior faculty from being able to devote sufficient time to mentor junior faculty. As such, the committee piloted an interdisciplinary approach and included mentors outside the department and College of Medicine to compensate for the low number of available mentors in Medicine (e.g. Public Health).

Methodology

A concurrent mixed method design was applied. We triangulated quantitative (numerical) and qualitative (descriptive) data to provide a comprehensive analysis of the primary usage patterns related to search and match behavior, and understand satisfaction with the online tool (13). We generalized results to our sample and then explored nuances based on narrative feedback.

Implementation

With the official launch of the mentoring program in January 2012, Mentor Match© went live to connect over 100 physician-faculty and faculty-researchers. At this time, the Department of Medicine had 65 junior faculty in search of mentors. A combined total of 54 mentors (N=32 full professors; N=22 associate professors) from the Department of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, and College of Public Health served as mentors for this group.

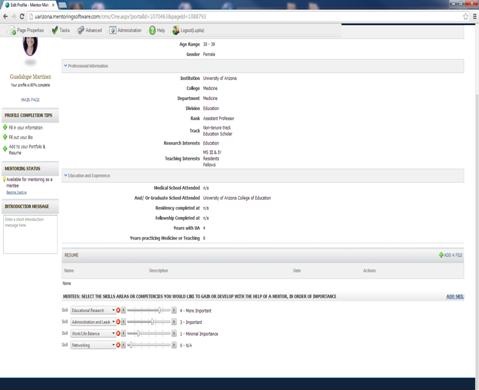

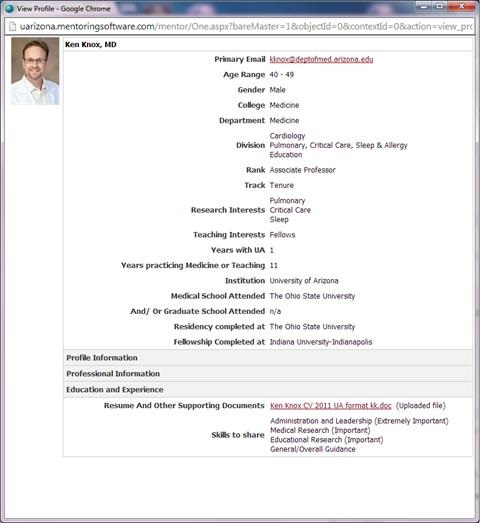

Faculty profiles include email addresses and detailed background information about each faculty member (e.g. academic track, age range, overall years teaching) (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. University of Arizona department of medicine mentor/mentee profile and skills inventory.

Figure 3. University of Arizona department of medicine mentor/mentee profile and skills inventory.

Once faculty data is entered, Mentor Match© produces a complete listing of top recommended mentors based on similarities between mentees and mentors. One-on-one demonstration of how Mentor Match© works occurs during new faculty orientation. Current CVs are uploaded and available for in depth review of publication record, training history and current funding. Junior faculty can also access other junior faculty profiles in the department to form peer mentoring groups.

Participants, data, and analysis

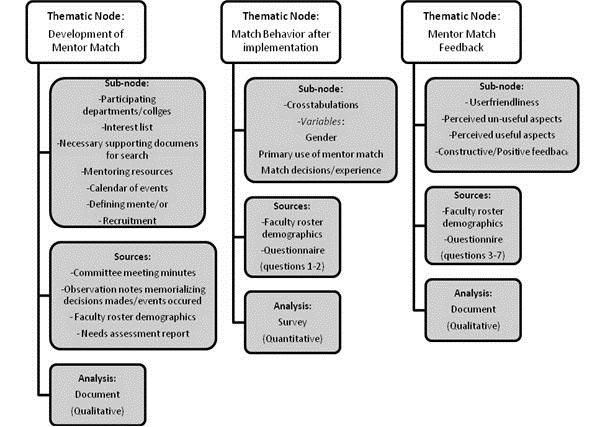

Voluntary mid-year and annual assessments are components of the mentoring program. IRB approved questionnaires developed by the committee were disseminated to program participants as part of a broader study and program quality control. For ongoing program evaluation and to inform the committee, we collected data from five sources: a) committee meeting minutes, b) observation notes, c) human resources faculty rosters from 2011-2012; 2012-2013, d) 2011 junior faculty needs assessment report, and e) voluntary end-of-the-year questionnaires.

Study participants included only mentee MD’s, DO’s, PhD’s, MD/PhD’s, and MD/MPH’s with the rank of Assistant Professor, Lecturer or Research Scholar in the Department of Medicine on one of three faculty tracks: clinical-educator, clinical, and research.

Cross tabulations formulated in SPSSv21 were used as part of survey analysis to compare categorical data from faculty rosters and questionnaires relevant to matching behavior and usage patterns. Qualitatively, document analysis using thematic coding for trend identification was conducted using Nvivo 10 to analyze narrative comments. Similarly, document analysis and thematic coding was implemented on committee meeting minutes, observation notes, and faculty roster to report the events and decision making process involved in the implementation of the program and matching tool (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4. Mentor match questionnaire (end-of-year).

Figure 5. Analysis coding scheme for setting description in methods and results.

Results

The program began with 65 mentees in January 2012. After annual faculty attrition, 72% of mentees (44/61) reported using the software and completed the voluntary end-of-year questionnaire in January 2013.

Selection patterns

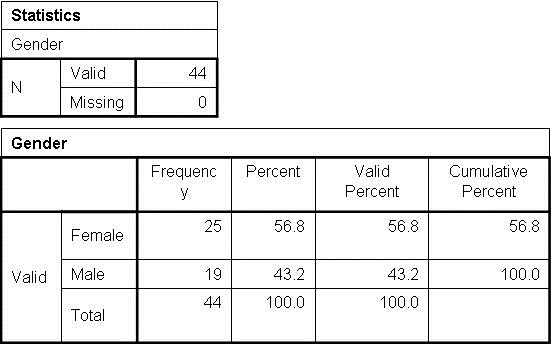

Mentees were asked to report their primary use of Mentor Match©. Three usage patterns were apparent (Appendix D, Table 1.0a). Over half of mentees reported primarily using the software to search for potential mentors both in and out of the department. Almost a third of mentees reported mainly using the software to search for potential mentors within the department only. Just under 10% (4/44) of mentees reported primary usage of the software to expand their professional peer network. Slightly over half of males utilized the software to search for potential mentors both in and out of the department. However, among females, this latter usage pattern was even more prevalent (17/25; 68%). Among those reporting primary usage to search for professional network expansion, males reported this practice at a disproportionately higher rate (3/19; 15%) than that of their female counterparts (1/25; 4%).

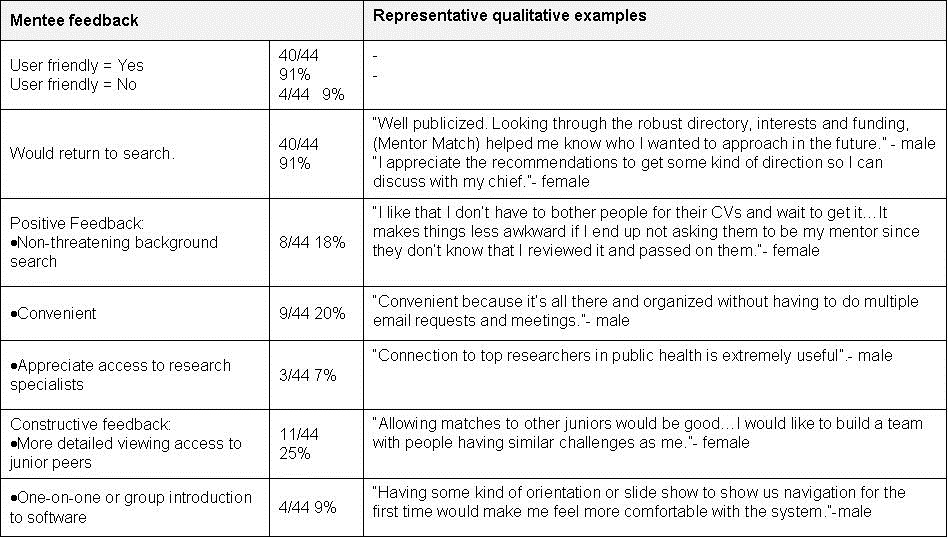

While mentees considered the recommended list of potential mentors from Mentor Match© in their match decision, just over half reported negotiating their primary mentor selection with their division chief’s recommendations (25/44; 57%). This means that mentees discussed their search results and interests with their chief to come to an agreement about who would serve as their mentor (Tables 1-3).

Table 1. Questionnaire results: gender.

Table 2. Questionnaire results: Search and matching behavior after Mentor Match© implementation in the department primary use and gender cross tabulation.

Table 3. Match results and gender cross tabulation.

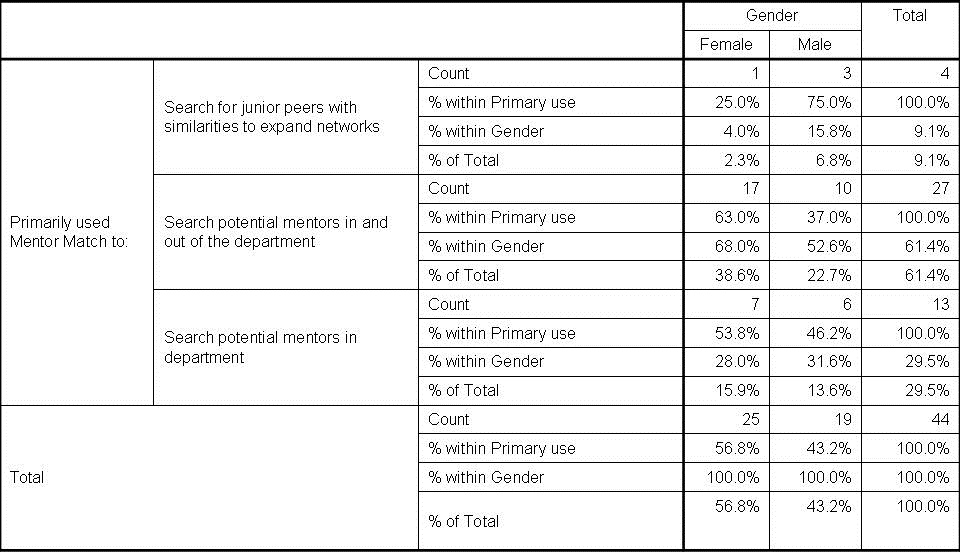

In this “negotiation” the mentee and chief come to a consensus instead of the chief assigning a partnership with no input from the mentee, a relatively common practice prior to this mentoring initiative. For the mentee, there is a sense of self-matching with guidance from the chief. This match pattern occurred proportionate to the respective totals of male and female mentees. An extremely small minority of junior faculty, all males, did not have mentors at the time of data collection (2/19; 10.5%). Finally, the next most common match patterns were the forced assignment (9/44; 20%) followed by the self-matched (8/44; 18%). At almost an even rate, female (5/25; 20%) and male (4/19; 21%) mentees reported considering the software’s top recommended mentors, but were ultimately assigned a mentor by their division chief. Remaining mentees (4/25; 16% females and 4/19; 21% males) reported considering the software’s recommendations, but eventually self-matched to a mentor of their choice.

Mentee feedback

The vast majority of mentees (40/44; 91%) found the software user-friendly, reporting that they would use the software for ongoing searches (Table 4). Questionnaire comments included positive feedback. Mentees’ appreciated the: a) non-threatening forum enabling access to detailed information about potential mentors, b) forum’s convenience, and c) functionality allowing access to research scholars outside the department. Finally, recommended improvements called for introductory training on website navigation, and viewing access to junior peer profiles.

Table 4. Mentee feedback.

Discussion

Building on Zerzan et al.’s (9) guide, we provide a robust description of implementing a software-based mentoring program. This software serves as a faculty directory and matching tool to facilitate mentors-mentee relationships in a large clinical department. Our systematic approach toward matching is a first step toward examining the use of technology to ease the search and match process for junior physician-faculty. We discovered that a “negotiated approach”, where junior faculty Mentor Match© selections were then explicitly discussed with division chiefs and department heads, was highly used and valued. Our data suggest that knowledge of local organizational culture or other information that can only be imparted through discussions with their chiefs and colleagues, are also highly valued.

Sambunjak et al.’s (10) qualitative study highlights the complexity of navigating partnerships. Our findings extend these observations to the search and match process, which is just as complex. More in-depth examination of the decision making process for those using software based matching or self-matching is needed to better understand what leads to junior faculty securing successful mentoring relationships. The shortage of mentors found in our needs assessment mirrored findings from national studies,11,12 implying that mentoring junior faculty is a challenge or not a priority compared to students, residents, and fellows. Given today’s heavy emphasis on clinical productivity and formal responsibilities teaching \ trainees at all levels, inspiring senior faculty to mentor junior faculty could be particularly difficult (5,15). Departmental leaders and program administrators must realize mentor shortages will impact the search experience regardless of methodology employed. The consequences of not addressing barriers in mentorship may include frustration with the search process, junior faculty turnover, and erosion of an important part of the academic culture. In addition to heeding recommendations by Straus et al. (3) of providing protected time and formal recognition for mentoring, departments should foster interdisciplinary networks inside and outside of the medical discipline, leverage the emeritus professor workforce, and embrace mentor panels. Technology based mentor searches could facilitate implementation of such initiatives with the goal of improving professional satisfaction among mentees.

Limitations

Our study examines the usage patterns of and feedback on Mentor Match© from the junior faculty mentee perspective, but there are limitations. First, we have not assessed whether and how mentors use Mentor Match© to research mentees who have reached out to them. Knowing if immediate access to mentees’ backgrounds and skills assists mentors in deciding whether to accept a mentorship or refer them to a colleague could inform us about the potential benefits of this software tool for mentors. This study also draws on a small mentee self-reporting sample in one department with just over half of all junior faculty participating. Although the sample is small, particularly regarding software feedback, findings provide a starting point to learn the technological needs of faculty related to the search and match challenge. Such data helps us tailor online profiles and site navigation. Finally, we also do not know whether there is a significant advantage to “negotiated” mentorships as compared with those established solely by using Mentor Match©.

Despite these limitations our study is the first to assess the role technology could play in the search and match process for physician-faculty. Casting the online matchmaking net more broadly to include other colleges and including trainees could add another dimension toward understanding how to improve the search and matching process in academic medicine.

Conclusion

Our study details Mentor Match© implementation and illustrates that software driven approaches can assist physician-faculty in establishing mentoring relationships. This approach may complement other search and matching efforts ongoing in departments and may be used to connect faculty across disciplines. In general, this tool continues to have a positive impact in our department, helping to achieve our goal of facilitating and expanding the mentee’s professional networks.

Acknowledgments

Role of each author in manuscript preparation:

- Dr. Martinez is the lead author of this paper. Participation included mentoring program committee membership, IRB documentation, data collection, study design, analysis, initial manuscript draft, revision implementation, approve final version.

- Dr. Lisse’s participation included mentoring program committee membership, questionnaire design, manuscript review/editing, approve final version.

- Dr. Spear-Ellinwood’s participation included data member checking, manuscript review/editing, approve final version.

- Dr. Fain’s participation included mentoring program committee membership, questionnaire design, study design, manuscript review, approve final version.

- Dr. Vemulapalli’s participation included mentoring program committee membership, questionnaire design, study design, approve final version.

- Dr. Szerlip’s participation included chairing the mentoring program committee, manuscript review/editing, approve final version.

- Dr. Knox is the senior mentor on this paper. Participation included mentoring program committee membership, IRB documentation review, study design, questionnaire design, manuscript review/editing, approve final version.

Funding:

This study was partially funded by an internal educational research award by the University of Arizona College of Medicine Academy of Medical Education Scholars in November 2012 and the Department of Medicine Administration.

Secondary Publication Notice:

This descriptive article is an unabridged report. A 500 word version of the full length manuscript is under review for primary publication in Medical Education’s Really Good Stuff section. This section presents short reports that illustrate general lessons learned from innovation in medical education, and include very little data and description.

References

- Savage HE, Karp RS, Logue R. Faculty mentorship at colleges and universities. College Teaching. 2004;52(1):21-4. [CrossRef]

- Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusie, A. Mentoring in academic medicine: A systematic review. JAMA. 2006;6(9):1103-15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straus SE, Chatur F, Taylor M. Issues in the mentor-mentee relationship in academic medicine: A qualitative study. Acad Med. 2009;84(1):135-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson VA, Palepu A, Szalacha L, Caswell C, Carr PL, Inui T. Having the right chemistry: A qualitative study of mentoring in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78(3):328-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pololi L, Knight S. Mentoring faculty in academic medicine: A new paradigm? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):866-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson CA, Morahan PS, Sachdeva AK, Richman RC. Effective faculty preceptoring and mentoring during reorganization of an academic medical center. Med Teach. 2002; 24:550-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams LL, Levine JB, Malhotra S, Holtzheimer P. The good-enough mentoring relationship. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28:111–5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada K, Slantez PJ, Boiselle PM. Perceived benefits of a radiology resident mentoring program: Comparison of residents with self-selected vs assigned mentors. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2014;65(2):186-91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerzan JT, Hess R, Schur E, Phillips, RS, and Rigotti, N. Making the most of mentors: A guide for mentees. Acad Med. 2009;84(1):140-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):72-78. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Data and Analysis: Faculty roster. Distribution of full-time faculty by department, rank, and gender. 2012. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/305522/data/2012_table3.pdf (accessed 12/8/14).

- Stacy J, Williams LP, Blair-Loy M. Medical professions: The status of women and men Center for Research on Gender in the Professions University of California- San Diego; 2013. Available at: http://crgp.ucsd.edu (accessed 12/8/14).

- Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2009.

- DeCastro R, Sambuco D, Ubel PA, Stewart A, Jagsi R. Mentor networks in academic medicine: moving beyond a dyadic conception of mentoring for junior faculty researchers. Acad Med. 2013;88(4):488-96. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger TJ, Ander DS, Terrell ML, Berle DC. The impact of the demand for clinical productivity on student teaching in academic emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:1364-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Reference as: Martinez GF, Lisse J, Spear-Ellinwood K, Fain M, Vemulapalli T, Szerlip H, Knox KS. Finding a mentor: the complete examination of an online academic matchmaking tool for physician-faculty. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2014;9(6):320-32. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc138-14 PDF