A Qualitative Systematic Review of the Professionalization of the Vice Chair for Education

Tuesday, June 21, 2016 at 8:00AM

Tuesday, June 21, 2016 at 8:00AM Guadalupe F. Martinez, PhD

Kenneth S. Knox, MD

Department of Medicine

University of Arizona

Tucson, Arizona. USA

Abstract

Background

Pulmonary/Critical Care physician-faculty are often in academic leadership positions, such as a department chair. As chairs are responsible for the success of their education programs, and given the increased complexity involved in evaluating learners and faculty increases, chairs are turning to colleagues with expertise in education for assistance. As such, vice chairs for education (VCE) are being introduced into the mix of academic executives to respond to the demands for accountability, training requirements, and professional development in a rapidly changing medical education climate. This review synthesizes the published literature around the VCE position.

Methods

An advanced electronic database and academic journal search was performed specific to the medical, medical education, and education disciplines. “Vice Chair for Education, Educational Leadership, (specialty) Residency Program Director” terms were used in these search processes. We conducted a qualitative systematic review of VCE literature in the English language published from January 1, 2005 to April 1, 2016.

Results

From the 6 studies screened, 4 were excluded and 2 full-text articles were eligible and retained for review. Both studies were cross-sectional and published between March and August of 2012 with response rates above 70%. Each employed quantitative and qualitative methods. The studies report important demographics and job duties of the vice chair.

Conclusion

The vice chair for education in academic medical departments has emerged as an important position and is undergoing professionalization.

Abbreviation List

AAIM-Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine

PRISMA-Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

VCE-Vice Chair for Education

Introduction

Schuster and Pangaro (1) introduced the pyramid of educators concept in their book chapter, Understanding Systems of Education in 2010. They designate the top of the pyramid as the institutional leaders or “academic executives” of the medical education system. These leaders include positions such as department chairs, deans, and CEOs. Pulmonary/Critical Care physician-faculty are often in leadership positions such as these. Locally, at our southwest institution and affiliate training hospital, the senior vice president for health sciences, chief medical officer, internal medicine department chair, vice chair for education, vice chair for quality and safety, internal medicine residency director, and one of the three associate residency directors are all pulmonary/critical care physician-faculty. Nationally, according to the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine (P. Ballou, AAIM email communication, May 2016), 12% (20/172) Internal Medicine department chairs are pulmonary/critical care/allergy physician-faculty belonging to the association to date. As chairs are responsible for the educational success of their programs, and given the complexity involved in evaluating learners and faculty, department chairs are turning to colleagues with interest and expertise in education for assistance. Vice chairs for education (VCE) are now being introduced into the mix of academic executives. Although the VCE role may vary by institution, VCEs are likely to respond to the demands for accountability, training requirements, and professional development in a rapidly changing medical education climate.

According to sociologists DiMaggio and Powell (2), one way to respond to external pressures is to create and legitimize new positions intended to better manage changes and demands. They go on to define this process as a professionalization of a position. Despite the emergence of the prominent and potentially pivotal position of the VCE, the formal recognition of this position and clarity of its purview over the educational mission remains obscure. In addition to synthesizing the published literature around the VCE position, we sought to determine two points that could best inform the medical education community about this position and future directions for educational leadership. First, is the role of department VCE defined in the academic literature? Second, what evidence exists that the position has professionalized in academic medicine?

Methods

In adherence with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (3) guidelines, we conducted a qualitative systematic review of VCE literature in the English language published from January 1, 2005 to April 1, 2016. The authors adapted the Cochrane Collaboration and developed and followed a specific search protocol a priori (4-5). The protocol is summarized below and detailed in Table 1. Institutional Review Board approval is not necessary for literature reviews.

Table 1. Search protocol in adherence to the Cochrane Collaboration

|

1. Text of the review |

a. Background: As department chairs are responsible for the educational success of their learners and faculty in academic medical centers, changes in how they delegate and manage the educational mission are evident. VCEs are now being introduced into the mix of academic executives to respond to the demands for accountability, expertise and leadership from changing medical education climate. Despite this important role, the formal recognition of this position and clarity of their purview over the educational mission has remained obscure. b. Objectives of the study are to: i) review how well-defined the role of the department vice chair for education is medicine education institutions, and ii) understand to what extent the position is professionalizing and becoming institutionalized. iii) gain insight into the above via synthesis and appraisal of relevant literature. |

|

|

2. Criteria for selected studies for review |

Exclusion Non-English works Commentaries Perspectives Newsletters Lone job descriptions Unpublished under-review research reports

|

Inclusion English language works Peer-reviewed published or in press qualitative, quantitative mix-methods original research reports, or articles with a research component Book chapters dedicated to the role solely Written between: January 1, 2005*-April 1, 2016 *Average of Brownfield (9) and Sanfey (5y) mean years since the establishment of the position as reported in 2012 publication (12y; 8y) |

|

3. Search strategy |

a. Email outreach to national VCE- Internal Medicine and Emergency Medicine interest group and listserv for the purposes of: i) triangulation ii) accessing submitted, in press, and unpublished work iii) accessing grey literature such as white papers and institutional reports. b. Electronic search consisting of the following relevant journals: Academic Medicine American Journal of Medicine Medical Education Journal of American Medical Association American Educational Research Association Journal of Surgical Education Medical Teacher The American Journal of Surgery e. Ancestry search of inclusive study references for snowball e-searches. f. Relevant database search of the following: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews ERIC MEDLINE PubMed Research Gate Science Direct Zotero f. Search engines: Google scholar g. Conference proceedings for specialty educational associations (Internal Medicine; Anesthesia, Surgery, Emergency Medicine, Pediatrics, Dermatology, Family Medicine, Psychiatry) h. Word search: Vice Chair for Education, Educational Leadership, (Specialty) Program Director |

|

Search protocol

The first author completed an advanced electronic database and academic journal search that included those terms specific to the medical, medical education, and education disciplines. “Vice Chair for Education, Educational Leadership, (specialty) residency program director” terms were used in these search processes as well as the search engine examination. The first author also conducted an ancestry search of the references listed in the screened literary pieces. The authors reached out to a national interest group made up of primarily VCEs in Internal Medicine via a national VCE email distribution list to combat publication and database bias, and gain knowledge about any existing grey literature, conference proceedings, unpublished or recently submitted works. Hand searches were not conducted as the ancestry search found the earliest relevant and indexed piece to be in 2012. Additionally, most journals have moved historic volumes as of 2005 to an online interface.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Authors set inclusion criteria to be qualitative, quantitative mix-methods original research reports or articles with a research component. Reports were to be full-text peer-reviewed works published or “in press.” Additionally, book chapters dedicated solely to the VCE role were considered.

Excluded were commentaries, perspectives, newsletters, pure job description documents, unpublished research reports or articles and those in “under review” status.

Data appraisal and extraction

Framework analysis (6), citations and full-text articles were charted, indexed, identified for themes, and finally, mapped and interpreted to collect and examine text for review. Appraisal of methodological soundness, reporting, and contribution to knowledge was conducted once full-text articles were identified for review. Validated quality assessment tools for quantitative and qualitative works were implemented and are discussed later in this review.

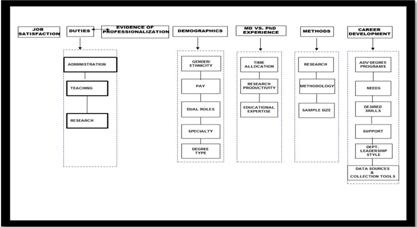

During the ancestry search, citations were imported into Endnote. Full study documents were imported into QSR Nvivo 10 software for analysis. Data categories and coding were developed via consensus building between the authors as part of the analytical framework Figure 1.

Figure 1. Thematic coding and concept mapping. As a method of mapping methods for qualitative data structuring, this concept map illustrates themes that emerged from data. Concepts are linked to demonstrate the relationships between them. Similarities, differences, strengths, and weaknesses were identified and threaded throughout each domain-or branch of the map that focuses on a particular aspect.

The first author began the initial coding process and queries followed by member checking by the senior author to improve categorization credibility. No initial categorization discrepancies between the authors occurred.

Results

Search results

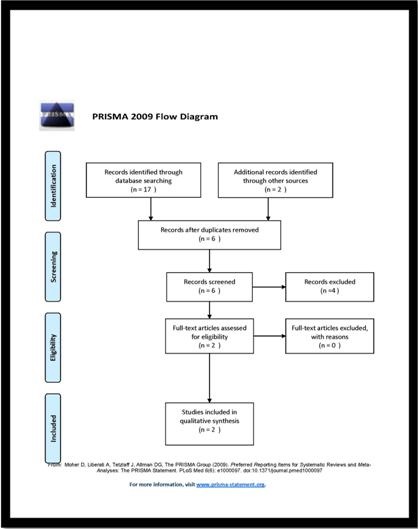

From the 6 screened studies, 4 were excluded and only 2 full-text articles were eligible for review. See Figure 2 for detailed PRISMA flow diagram.

Figure 2. PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram. The diagram depicts the flow of information throughout the systematic review. Mapped are the number of records identified, included and excluded.

Study characteristics

Both studies were cross-sectional and published between March and August of 2012 with response rates above 70%. Each employed quantitative and qualitative methods, but each favored one method Table 2.

Table 2 List of relevant, but excluded literature and justification

|

Author |

Month/Year Published |

Literary Type/Topic |

Focus/Justification for final exclusion |

|

Sanfey et al.14 |

March web content and July 2012 |

Web-based and article based Review/VCE scope of duties and qualifications |

Brief website review of the authors’ previous work that delineates VCE qualifications for MDs and PhD educators, career development opportunities, and job description with specific workloads for each mission. The authors offer sections on career advice specific to time management, acquiring a national reputation, funding for educational research activities, and resource sites to find a VCE position. Excluded as this is a review and career offerings are opinion-based. Via a surgical organization task force, the online material underwent a slight title modification. This online review of the original research was subsequently published in print with the American Journal of Surgery. |

|

Pangaro15 |

August/2012 |

Commentary/VCE and direction for future educational leadership |

Highlight gaps in nation’s overall approach to medical education. Offers a paradigm shift calling for medical education to use evidence-based data, and educational theory to inform future directions and departmental leadership. Innovation and creativity is stressed. In this spirit, there is a call for a specific leadership style (collaborative) on the side of the Chair that could likely empower the VCE role. Insightful and relevant for future directions, but excluded as the commentary is opinion-based. |

|

Wolfsthal et al.16 |

|

Book Chapter/Internal Medicine Program Residency Director Job Description |

Seven page chapter in the internal Medicine association’s textbook for medicine education programs. This chapter outlines the job description of Internal Medicine program directors. One paragraph with 5 bullet points articulates that the VCE role may be combined with that of the Internal Medicine Residency Program Director role. This chapter does serve as additional evidence of dual leadership roles that appear as a trend among the VCE and internal medicine departments. However, excluded as chapter is not dedicated solely to the VCE position and integrated, in-depth, with the PD position. |

Sanfey et al. (7) is a quantitative work that provides basic descriptives with means. A job description with specific categories is the qualitative element presented. Participants were 20 MD surgeons and 4 PhD educators serving as VCEs in departments of surgery. One data collection instrument was used and consisted of an online survey with Likert scales and open-ended questions with comment sections to gather short narrative responses.

Though Brownfield et al. (8) employed both quantitative and qualitative methods, the study was dominated by an inductive qualitative approach. Participants included 59 MDs serving as VCEs in departments of internal medicine. The primary source of data was VCE responses to an online survey comprised of open-ended questions to collect narratives.

Appraisal of studies

Each report was appraised by the authors. We applied Spencer et al.’s (9) appraisal of qualitative work, the National Collaborating Center for Methods and Tools (10), and Jack et al.’s (11) quality appraisal tools for basic descriptive statistics. Post scoring and deliberation, studies were categorized into either: low, moderate, good, or high quality studies. This process helped us make an informed decision regarding the quality of the research reports. The qualitative assessment tool was applied to Brownfield et al. (8). Scores between the authors ranged from 35 to 44 (maximum score of 72) and a mean score of 39.5 (8). Sanfey et al.’s (7) qualitative scores ranged from 30 to 41 and a mean score of 35.5; quantitative scores ranged from 14-15 (maximum score of 18) and a mean score of 14.5 (7). In all, both reports were of good quality (scale consists of low-good-high categories), methodological rigor, reporting, and knowledge contribution. Studies note sufficient and important limitations regarding relatively small sample sizes, non-responder bias potential, and limitations to just two fields: surgery and medicine.

Synthesis of study findings

Although both research reports were related to the VCE role, there was substantial heterogeneity in their study aims that allowed for a broad conceptualization of the role. One study was largely to create a career development path for VCEs on a national level, while the other sought to establish, in detail, the roles and responsibilities of VCEs.

Similarities. Both studies had VCEs as the primary data source with the Brownfield et al. (8) work implementing follow up member checking with a group of VCEs at a national conference. Both also refer to the elevated expectations from institutions and accreditation agencies for evidence driven education and administrative practices as an external force that has led department chairs to create the VCE role. However, these studies noted that the clerkship and residency director roles have job descriptions and recommended protected time established by national accreditation bodies. Notably absent is a formal job description for the VCE role. As such, informed by their data, these studies set precedent by establishing a job description by providing lists of expected duties and activities. These duties not only centered on program and director oversight, but reflected a value system that appreciated autonomy, educational expertise, promotion of educational scholarship and investment in the further development of leadership skills.

In terms of demographics, both studies found that VCEs were more likely male, senior MD professors with additional training in education. Formal establishment and recognition of the position is difficult to deduce from the studies. Each study identified the position as “relatively new.” They both cite this as a reason to explain why participants reported uncertainty in their responsibilities and the lack of a formal job description. VCEs in both studies served in the position for a widely variable number of years ranging from 6 months to 25 years. Distribution of protected time for the role was addressed. However, Sanfey et al. (7) provide a snap shot of participants’ work load distributions with ascribed percentages to each of the institutional missions. In terms of preparation for the role, they went into greater detail about expectations. The investigators note a national increase in educational graduate programs in academic medicine and suggest chairs seek VCEs with backgrounds in graduate medical education in order to meet the demands and expectations of the position.

Differences. Sanfey et al. (7) reviewed the academic preparation for the VCE position, terms of employment, expected scholarly productivity, and took inventory of participants’ job satisfaction as well as specific leadership skills they desired to acquire and improve upon. In this study there was comparison between MD and PhD educators’ time allocations, and demographics. Closing their report, Sanfey et al. (7) discussed recruitment strategies for the hiring of VCEs, and stressed the importance of education portfolios and educational research productivity among potential candidates. Furthermore, they provided recommendations to those in hiring positions to strongly consider PhD educators for the role given PhDs scholarly productivity outpaced those of their surgeon peers who often have time consuming clinical demands.

Methodologically, Brownfield et al. (8) state they ask for job descriptions in their data collection, but do not note actually triangulating these documents with survey responses. From survey responses and an in-person group follow-up meeting, Brownfield and colleagues (8) noted in-depth, dominant themes that emerged from those surveyed. Unlike Sanfey, they include how participants experienced the role, and if metrics for assessing their success were clearly established at their institutions. Despite a relatively robust set of reported responsibilities, most striking was the theme of reported uncertainty about the role among their participants. This was as a result from vague expectations or ill-defined purview. Brownfield and colleagues (8) provided a set of guidelines for current and prospective VCEs to consider that could potentially mitigate such an experience. A few include: the importance of transparency with the Chair about expectations, delegation, priority setting, and establishing an appropriate infrastructure of support.

Two themes that answer our research questions. Both studies a) formally identified and defined VCE duties, and b) documented the establishment and professionalization of the VCE position in departments of surgery and internal medicine in the U.S. Analysis indicated a theme wherein VCE roles and duties were defined in both works. However, the purview was dauntingly broad. As expected, multiple indicators of the professionalization, as defined by DiMaggio and Powell (2), of the VCE role in academic medicine exist within these two published studies. Both studies were published in quality journals (Academic Medicine (Impact Factor 3.292 at the time their study was published) and the Journal of Surgical Education (Impact Factor 1.634 at the time their study was published) (12-13). Moreover, data in these studies contributed to a formalized job description that set a vast scope of duties, broad oversight purview, working conditions, and career development needs of this group at a national level.

Discussion

The VCE role is designed to help the department navigate an ever changing, complex and diverse academic environment in medical education. Because these studies included only two disciplines, we believe the position remains ambiguous and not well-defined. It is clear the responsibilities of the position need refinement to maximize its impact within the department.

Both studies provide specific examples of the VCE responsibilities and roles with attention to how VCEs are expected to oversee educational programs. Brownfield et al. list position expectations that include: educational program oversight, promote scholarship and serve in leadership activities. Sanfey et al. (14) provided examples by subcategorizing responsibilities by i). administration, ii). teaching, and iii) research responsibilities. Both studies defined oversight as: setting the philosophical tone and course to move programs toward institutional and/or departmental vision; defining priorities; creating initiatives that would aid in program advancement; play a key role in redesigning evaluation technologies and methods; developing faculty reward systems; designing faculty development curriculum; consultant to all the educational directors in the department; advising the chair in faculty recruitment; chairing educational committees; training education staff regarding accreditation and strategic initiatives, and identifying and securing resources. Though broad, this collective list outlines responsibilities that are different than those presented in Wolfsthal et al. (16) job description of Internal Medicine residency directors and Foster and Clive’s (17) chapter on the Program Director as Manager. Unlike the VCE oversight examples that are illustrative of executive leadership, the current program director literature offers examples of managerial responsibilities to a single program. Responsibilities include: implementing policy and initiatives; setting agendas for meetings; budgeting basics; delegating authority; office personnel management, and time management. This distinguishes the VCE role from that of other departmental education positions such as the residency director. From the reviewed studies, VCE responsibilities are more vision-driven rather than managerial in nature (18).

Finally, it was unclear if the VCE position should be bundled with other administrative leadership roles. According to Brownfield et al. (8), this was pervasive in internal medicine as well. While we do not believe this is unique to one specialty, Sanfey et al.’s (7) work did not report dual leadership in surgery perhaps because the survey question was not asked. Regardless, the complexity in the Sanfey et al. (7) article was not as rich or apparent as Brownfield et al.’s study.

Given the emerging importance of this influential leadership role, we were surprised by the lack of a VCE recruitment strategy. In fact, both studies touch on the fact that the majority of participants were thrust into the VCE role with a small minority being promoted into the position internally. Neither study solicited the perspectives of department chairs, what they expect of the VCE and why they were chosen for the role. This practice is in stark contrast to the guidance provided by the articles where they provide discussion points and items to negotiate prior to accepting the VCE position. The data suggest a formal recruitment process with negotiation for educational resources is needed for the VCE position to realize its potential.

Yielding 2 full-text studies this review is not robust and thus, limits recommendations. Other medical disciplines may have similar roles, but no data has been published. Never-the-less the information in this review is educationally significant. This review serves as a critical starting point from which to gain knowledge about more nuanced educational leadership positions and their mobilization towards legitimacy, formal recognition, and time allocations in clinical departments. This review documents the professionalization of the VCE role in the academic community in its infancy.

As many pulmonary/critical care physician-faculty make up the top administrative and educational leadership roles at our institution, we speculate that pulmonary/critical care and practice lends itself to leadership in academics. Building relationships with multidisciplinary ICU teams is much like building academic leadership teams. The skills necessary to articulate sensitive information to family members of critically ill patients provides a foundation for dealing with the most challenging aspects of administrative leadership discussions that are inherent to academe. Defining successful leaders and studying the personality traits of those from medical specialties would provide further insight and are ongoing.

Scholars are encouraged to consider research pertaining to the VCE role and to move beyond the job description to study the value the position brings to the department. Studies should include department chair perceptions of the position in the changing education and healthcare landscape, and whether these types of roles are more appropriately suited for particular medical disciplines over others. Examining the academic culture of departments to inform the desirable dynamic for the VCE is important. A starting approach can tease out how this role is impacted by departmental relationship dynamics, behaviors, and values. Finally, future studies that include robust examination of the VCE relationship with the chair would triangulate the existing body of work, and could validate what we know about educational leadership and academic executives.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Carole Howe, MD, MLS of the Arizona Health Sciences Library for her guidance regarding database searches, and the University of Arizona College of Medicine Department of Medicine for allowing research time to conduct this review.

Authors also thank Ms. Sarah Almodovar for her time preparing and reviewing this work.

Finally, the authors thank those on the Vice Chairs for Education in Internal Medicine national interest group distribution list for responding to inquiry for grey literature knowledge, clarification questions, works in press, and unpublished works. We thank the National network of VCE responding to inquiry for grey literature knowledge, clarification questions, and unpublished works: Drs. Michael Frank, Stephanie Call, Erica Brownfield, Alan Harris, John Mastronarde, Bradley Allen, Ellis Levin, Lisa Bellini, Gerald Donowitz, Joel Thorp Katz, and Susan Wolfsthal.

References

- Schuster B, Pangaro L. Understanding systems of education: What to expect of, and for, each faculty member. In: Pangaro L, ed. Leadership careers in academic medicine (Ed Louis Pangaro). Philadelphia, PA: ACP Press; 2010.

- DiMaggio PJ, Powell W. The iron cage revisited:institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review. 1983;48:147-60. [CrossRef]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009; 6(6): e1000097. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook DA, West CP. Conducting systematic reviews in medical education: a stepwise approach. Med Edu. 2012;46:943-952. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlosser R. Appraising the quality of systematic reviews. FOCUS. 2007. Technical Brief no. 17.

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. Sep 2013;13:117. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanfey H, Boehler M, DaRosa D, Dunnington GL. Career development needs of vice chairs for education in departments of surgery. J Surg Educ. Feb 2012 69(2):156-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownfield E, Clyburn B, Santen S, Heudebert G, Hemmer PA. The activities and responsibilities of the vice chair for education in U.S. and Canadian departments of medicine. Acad Med. Aug 2012;87:1041–5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, Liz; Ritchie, Jane; Lewis, Jane; Dillon, Lucy & National Centre for Social Research (2003). Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/498322/a_quality_framework_tcm6-38740.pdf . Accessed March 22, 2015.

- National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools (2012). Qualitative research appraisal tool. Hamilton, ON: McMaster University. (Updated 03 October, 2012) http://www.nccmt.ca/resources/search/148 Accessed March 22, 2015.

- Jack L, Hayes SC, Jeanfreau SG, Stetson B, Jones-Jack NH, Valliere R, LeBlanc C. Appraising quantitative research in health education: guidelines for public health educators. Health Promotion Practice. 2010;2:161-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Impact factor citation https://www.researchgate.net/journal/1040-2446_Academic_Medicine Accessed April 2, 2016.

- Impact factor citation https://www.researchgate.net/journal/1931-7204_Journal_of_Surgical_Education Accessed April 2, 2016.

- Sanfey H, Boehler M, Darosa D, Dunnington GL. Career development needs of vice chairs for education in departments of surgery. J Surg Educ. 2012 Mar-Apr;69(2):156-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pangaro LN. Commentary: getting to the next phase in medical education--a role for the vice-chair for education. Acad Med. 2012;87(8):999-1001. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfsthal S, Call S, Wood V. Job description of the internal medicine residency program director. In: Ficalora RF, Costa, ST, eds. The Toolkit Series: A Textbook for Internal Medicine Education Programs. 11th ed. Alexandria, VA: AAIM; 2013. Foster RM, Clive DM. Program director as manager. In: Ficalora RF, Costa, ST, eds. The Toolkit Series: A Textbook for Internal Medicine Education Programs. 11th ed. Alexandria, VA: AAIM: 2013.

- Foster RM, Clive DM. Program director as manager. In: Ficalora RF, Costa, ST, eds. The Toolkit Series: A Textbook for Internal Medicine Education Programs. 11th ed. Alexandria, VA: AAIM: 2013.

- Naylor CD. Leadership in academic medicine: reflections from administrative exile. Clin Med September/October 2006 6(5) 488-92. [CrossRef] [Pubmed]

Cite as: Martinez GF, Knox KS. A qualitative systematic review of the professionalization of the vice chair for education. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2016;12(6):240-52. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc044-16