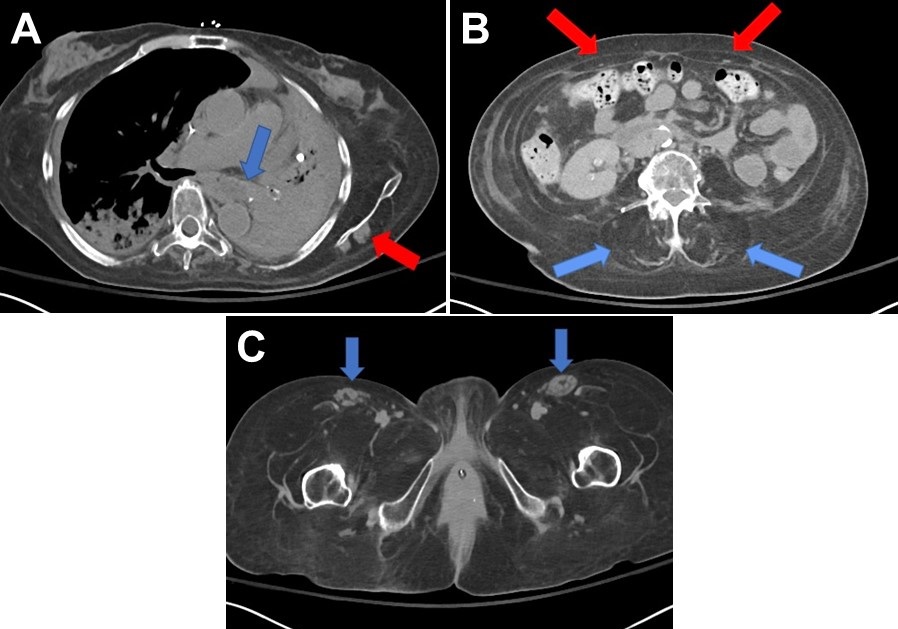

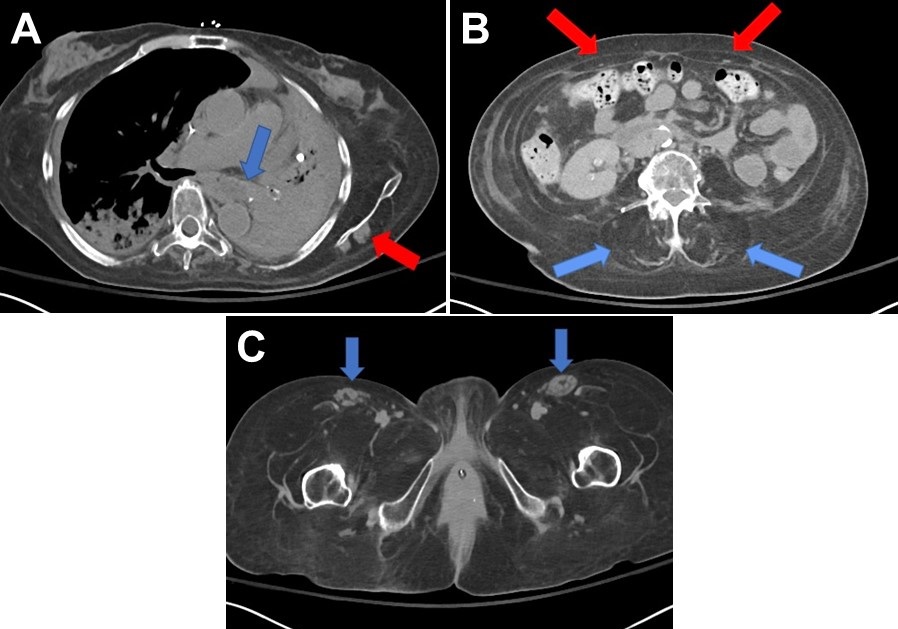

Figure 1. Non-contrasted CT scans. A: Chest CT demonstrates a large mucous plug in the left mainstem bronchus (blue arrow) resulting in complete collapse of the left lung. There is near complete fatty replacement of the musculature of the shoulder girdles except for a small residual portion of the left infraspinatus muscle (red arrow). B: Abdominal CT demonstrates fatty replacement of the rectus abdominis musculature (red arrows) and lumbar musculature (blue arrows) consistent with the patient’s history of Pompe disease. C: Pelvic CT demonstrates near complete fatty replacement of the muscular compartments of the thigh except for residual portions of the bilateral sartorius muscles (blue arrows).

Clinical Presentation: A 63-year-old lady with a past medical history significant for late-onset Pompe disease complicated by chronic hypoxemic and hypercarbic respiratory requiring continuous mechanical ventilation via a tracheostomy tube presented to the emergency room from her care facility with worsening hypoxemia. She had been feeling poorly for three days prior to her presentation with fevers, chills, and thicker secretions from her tracheostomy tube with routine suctioning.

On arrival, she was febrile with a temperature of 39 °C and had diminished breath sounds on the left. Her lab work demonstrated a leukocytosis along with an increase in her creatinine consistent with acute kidney injury. CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis (Figure 1) demonstrated collapse of the left lung secondary to a large mucous plug in the left mainstem bronchus and fatty replacement of most of her visualized skeletal musculature consistent with her diagnosis of Pompe disease. Sputum cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Through a combination of fluid resuscitation, antibiotics, and aggressive chest physiotherapy her clinical condition improved to the point that she was able to return to her care facility.

Discussion: Pompe disease results from a deficiency of acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA) which leads to the accumulation of glycogen resulting in tissue destruction (1,2). Adult patients present with progressive, proximal weakness in a limb-girdle distribution (particularly the hip flexors) along with respiratory insufficiency secondary to diaphragmatic involvement (3,4). Some patients may require noninvasive respiratory support and may progress to requiring mechanical ventilation (5). Diagnosis is made by clinical history and electromyogram. The rate of progression and sequence of respiratory and skeletal involvement vary substantially. Intravenous enzyme replacement therapy with alglucosidase alfa has shown efficacy for late-onset Pompe disease. Gene therapy is under investigation. In untreated patients with late-onset disease, the estimated 5-year survival is 95% and 40% at 30 years (6).

Zachary Hernandez MD, Kelly Wickstrom DO, and Tammer El-Aini MD.

Department of Pulmonary Medicine and Critical Care

University of Arizona College of Medicine

Tucson, AZ USA

References

- Hirschhorn R, Reuser A. Glycogen storage disease type II: Acid alpha-glucosidase (acid maltase) deficiency. In: The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease, Scriver C, Beaudet A, Sly W, Valle D (Eds), McGraw-Hill, New York 2001. p.3389.

- Raben N, Plotz P, Byrne BJ. Acid alpha-glucosidase deficiency (glycogenosis type II, Pompe disease). Curr Mol Med. 2002 Mar;2(2):145-66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel AG. Acid maltase deficiency in adults: studies in four cases of a syndrome which may mimic muscular dystrophy or other myopathies. Brain. 1970;93(3):599-616. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkel LP, Hagemans ML, van Doorn PA, Loonen MC, Hop WJ, Reuser AJ, van der Ploeg AT. The natural course of non-classic Pompe's disease; a review of 225 published cases. Neurol. 2005 Aug;252(8):875-84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellies U, Stehling F, Dohna-Schwake C, Ragette R, Teschler H, Voit T. Respiratory failure in Pompe disease: treatment with noninvasive ventilation. Neurology. 2005 Apr 26;64(8):1465-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Meijden JC, Güngör D, Kruijshaar ME, Muir AD, Broekgaarden HA, van der Ploeg AT. Ten years of the international Pompe survey: patient reported outcomes as a reliable tool for studying treated and untreated children and adults with non-classic Pompe disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2015 May;38(3):495-503. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Hernandez Z, Wickstrom K, El-Aini T. Medical image of the month: late-onset Pompe disease. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2020;20(4):124-5. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc022-20 PDF

Friday, May 1, 2020 at 8:00AM

Friday, May 1, 2020 at 8:00AM