Jessica R. Hurley, DO1

Kevin O. Leslie, MD2

1Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center, Phoenix, AZ

2Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ

Abstract

IgG-related systemic disease (ISD) remains exceedingly rare and unfamiliar, particularly extrapancreatic disease. We report a patient with separate presentations of IgG4 pulmonary disease and recurring IgG4 related biliary sclerosis and pancreatitis. Because of the intricate and perplexing pathogenesis, overlapping organ systems and wide variation in disease presentation, ISD in its entirety remains undefined. Accurate identification of ISD is critical to avoid permanent organ damage especially since treatment is nearly always successful with corticosteroids. As recognition and awareness of this disease grows, development of standard diagnostic criteria and treatment plans are needed.

Introduction

There has been increasing interest in IgG4-related systemic disease (ISD) as it becomes more recognized and the disease spectrum escalates. Initially thought to be limited to the pancreas and biliary system, ISD has recently been identified in virtually every organ system including several, varying pulmonary presentations (1). We present a case that demonstrates separate presentations of both pulmonary and pancreatobiliary disease.

Case Report

A 60 year old gentleman was evaluated for progressive dyspnea and radiographic defects that persisted for three months despite appropriate treatment for community acquired pneumonia. His past medical history was most notable for recurrent pancreatitis attributed to a common bile duct stricture requiring multiple stents. Pancreatic cancer had been ruled out with an endoscopically obtained brush specimen.

Physical exam findings were notable for bibasilar faint crackles. Pertinent work up findings included pulmonary function testing showing a mild restrictive lung disease and a six minute walk test that revealed oxygen desaturation to 88%. Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated bilateral, patchy consolidation with air bronchograms and focal areas, of dense, nodular-like tissue (Figure 1).

Figure 1. High resolution CT scan reveals patchy, bilateral ground-glass opacities, consolidation and nodules in both upper and lower lobes.

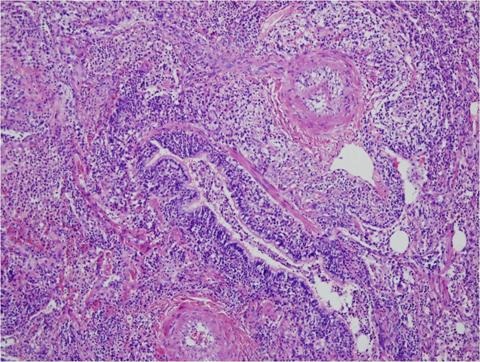

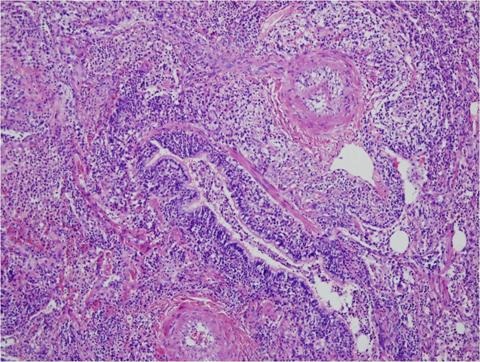

A surgical lung biopsy revealed dense, non-necrotizing granulomatous and fibrohistiocytic interstitial lung disease with vascular and pleural involvement (Figure 2).

Figure 2. H&E stain showing a plasma cell rich lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (*lymphocytes stained purple) in the bronchovascular sheath (both bronchiole and pulmonary arteries demonstrated here).

Histopathology diffusely stained positive for IgG4 plasma cells (Figure 3).

Figure 3. IgG4 immunohistochemical stain showing increased numbers of IgG4 positive plasma cells in the infiltrates (> 10 IgG4+ plasma cells per high power (40X) field).

The patient had a markedly elevated IgG4 of 2,830 mg/dL.

He was started on steroid therapy and one month into treatment his repeat chest imaging and serum IgG levels returned to normal and his respiratory symptoms resolved (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Repeat CT images six weeks after starting treatment revealed nearly complete resolution of the disease.

Subsequently the patient developed two separate episodes of recurrent pancreatitis, both responding to steroid treatment. His pancreatitis was re-diagnosed as IgG4-related biliary sclerosis and pancreatitis based on disease presentation, imaging and the rapid response to steroids. The patient has remained disease free and off steroid therapy.

Discussion

ISD was first described in the pancreas as an autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP). AIP has only recently gained recognition as an IgG4-related disease in the past decade despite the first description dating back to the 1950’s. Polish physicians Borszewski and Pancewicz-Olszewska (2) noted obstructive jaundice developing from chronic, fibrosing pancreatitis. In 1961 Sarles et al (3) described chronic scarring and inflammation in the pancreas as a potential autoimmune problem. It was another decade before researchers realized that elevated immunoglobulins were associated with AIP (4). In 2001, the IgG4 level was found to specifically correlate with histopathological changes in pancreatic tissue in AIP, aiding in the exclusion of other pancreatic dysfunctions (5). ISD was therefore thought to be restricted to the pancreas but by 2003, ISD had been identified in extrapancreatic tissue and since has been found in virtually every tissue type throughout the body, including the lung, first reported in 2004 (6, 7).

ISD is a relatively new and unfamiliar disorder that occurs when excessive amounts IgG4- positive plasma cells infiltrate organ tissue (8). This abundance of lymphoplasmacytes induces significant inflammation and fibrosis in the surrounding tissues and can occur in almost every organ system in the body including pancreas, gallbladder and biliary tree, salivary and lacrimal glands, liver, kidney, retroperitoneum, aorta, lymph nodes and lung (7,9,10).

ISD goes by many identities including “IgG4-related systemic sclerosing disease”, “IgG4-related sclerosing disease”, “IgG4-related disease”, “hyper-IgG4-disease”, and “IgG4-related systemic disease” (7, 8, 10, 11). We use IgG4-related systemic sclerosing disease (ISD) throughout this manuscript.

Symptoms and Presentation

It is unclear if ISD can exclusively occur in one organ without any pancreatic involvement, if it results from an overlap with other autoimmune systemic diseases, or if it is part of one entire systemic disease. Many case reports and studies that discuss pure extrapancreatic disease fail to rule out additional organ involvement (6, 12-15). There are several possible explanations for this. There are no concrete diagnostic criteria for ISD so rarely have asymptomatic organs been evaluated. Many patients who have been diagnosed with a form of ISD have had additional organ involvement discovered incidentally (12, 16, 17). This is especially true for many of the retrospective reviews sparked by the recent discovery and exploration of ISD (8, 12, 18). Because the disease can be asymptomatic and only found unintentionally on imaging or lab work (e.g. CT abdominal scan showing diffusely enlarged pancreas after routine labs showed transaminitis) or due to a secondary disease developing (such as diabetes mellitus type II) from ISD affecting the organ (such as chronic pancreatitis in AIP) (1, 11, 19). Also, many publications lack adequate length of follow up for the potential development of AIP and also fail to mention if the patients’ ISD was preceded by AIP. The timing of AIP development can vary and may precede extrapancreatic disease by years or develop months to years after the initial diagnosis (8, 19). Future case studies in light of advanced research may show otherwise, but for now extrapancreatic ISD seems to nearly always, if not always, occur in the setting of AIP.

It is important to note that nearly all of our knowledge regarding ISD stems from patients diagnosed with AIP as not only is this where ISD was first recognized, it is also the most frequently involved organ. Of the two AIP subclasses, type I has been established as the pancreatic manifestation of ISD (20). Both types share some overlap but vary in presentation epidemiologically, symptomatically, on imaging, on pathology, and treatment. Type I is found mostly in older patients with ages averaging over 60 years old although it has been reported ages 14 to 85 years (1) and appears to favor males with a 4 to 10:1 ratio compared to Type II with an average age of 52 years old and a female:male ratio of 8:10 (8, 10, 19, 20). Type I clinically presents with classical painless obstructive jaundice whereas type II is more likely to have chronic recurring abdominal pain (20). Type I AIP patients are also less likely to have allergic disorders or elevated IgE and eosinophilia (21). Histopathologically, Type I classically has elevated serum IgG4 levels and affected tissue infiltrated with IgG4+ plasma cells and lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis with hypercellular inflamed interlobular stroma compared to type II which has a neutrophilic infiltration surrounding the pancreatic duct with ulceration and abcess formation (20, 22). On imaging, the pancreatic tail cut-off sign was only seen in type II patients whereas type I features irregular pancreatic duct narrowing and diffuse or focal pancreatic enlargement with development of a capsule-like rim and loss of normal pancreatic architecture. Also, like all other organ systems affected by ISD, both types of AIP respond quickly to steroids but type I is more likely to recur (20, 22).

These features seen in type I AIP generally seem to transfer to all organ systems affected by ISD. Unfortunately epidemiologic data about ISD as a whole remains limited. This is due to under-recognizing the disease, in part because of its novelty, but also because up to half of all ISD patients may be asymptomatic (8, 9, 12, 19). Many patients are diagnosed incidentally through lab and imaging findings (6, 10, 12). A Mayo Clinic study divided patients with imaging evidence of AIP into three groups based on likelihood of being diagnosed with AIP. They found that even in the group most likely to have a diagnosis, 20% had normal IgG4 levels and/or no additional organ involvement in addition to 30% requiring a biopsy or steroid trial to diagnose AIP (23). Organs affected by ISD generally have signs and symptoms related to the involved organ. For example, diabetes mellitus is seen in up to two-thirds of patients diagnosed with type I AIP (1, 24). Lacrimal and salivary gland enlargement is seen in ISD of the head and neck (23). Patients with ISD of the lung may complain of a dry cough, shortness of breath and allergic symptoms such as sinusitis or rhinitis (9, 12). Systemic or infectious signs are rarely exhibited.

AIP in itself is quite rare, accounting for 11% of chronic pancreatitis and only 2% of this is type I (22). The amount of patients with pancreatic ISD is quite impressive, ranging from 50-80% (9). A majority (around 80%) are most likely to have biliary tree involvement compared to as few as 5% with affected lung (1). Initially all affected organs were reported in association with pancreatic involvement, however there are now increasing reports of what appear to be sole manifestations of ISD (26). Since AIP is not always caused by ISD and additional organ involvement was only recently associated with this IgG4 disorder, the extrapancreatic disease is now becoming increasingly researched.

What is IgG4 and Its role in ISD?

Immunoglobulins differ based on their heavy chain sequences and antigen receptor sites. Some types of antibodies expose their heavy chains to an antigen-binding site to allow a specific antigen to bond and form an immune complex. However, this is not the case with IgG4. Immunoglobulin (Ig) G is divided into four subsets, 1-4, IgG4 being the smallest and normally making up about 3-6% of serum totals (5). IgG is made of two heavy chain-light chain pairs connected by a disulfide bond which varies among the subclasses. In IgG4 the disulfide bonds between the heavy chains are unstable, thus they easily form bonds with other IgG4 Fc receptors (the area Ig binds to an antigen and generates a specific immune response) which prevents the exposure of the antigen-binding site, hence preventing an antigen from bonding. This means it does not activate the complement cascade. Although IgG4 does not bind complement, it does bind to CD64, i.e. FcgRI. CD64 is expressed on monocytes and macrophages and plays a role in opsonization and phagocytosis. Interestingly, IgG4 is capable of forming bispecific antigens due to a mechanism known as the Fab arm exchange (27). This occurs when a heavy-light chain is swapped with another molecule. This bispecific antigen could then interact with other immune complexes to prevent them from functioning properly and thus possibly decrease inflammation.

The induction and production of IgG4 is complicated and poorly understood. B cells create specific antibody isotypes depending on the cytokines in the B cell environment. Functionally, cytokines can be divided into two categories: inflammatory and anti-inflammatory. T lymphocytes vary based on the specific type of antigen receptor on their surface, the major co-receptor including either CD4 or CD8. CD4+ T cells, also called helper T cells, are the largest cytokine producers. There are two types of helper cells: Th1 which produces the cytokine interferon gamma (IFN γ) and acts as a proinflammatory, and Th2 creates interleukins (IL) 4, 5, and 13 that promote IgE and trigger eosinophils in allergic responses, as well as IL-10 which acts as an anti-inflammatory (28). The two types of cytokines are thought to keep each other balanced and that a disorder occurs if one form is in excess of the other. One study in 2005 evaluated the effect IL-10 had on Th1 and Th2 immune systems and demonstrated that IgG4 production correlated with IL-10 regardless if induced through a Th1 or Th2 immune process but not by solely using cytokines IL-4, IL-13, or IFN γ (29).

It has been determined that this cytokine, IL-10, is particularly important in IgG4 production. Jeannin et al. (30) examined the overlap in class-switching between IgE and IgG4 by inducing an allergic response in five patients and evaluating the response IL-10 had on IL-4-stimulated lymphocytes. They found that although IL-4 induced class switching to IgG4, this was pathway was increased and likely regulated by IL-10 (30). In addition to the cytokine IL-10 upregulating IgG4 secretion, there must also be an interaction between T and B cells for maximal production (29). These details were further exemplified recently when van de Veen et al. (31) discovered that B cells specific for a particular allergen, bee venom in this case, were found to express surface receptors CD73-CD25+CD71+. These B cells, once enriched, secreted high levels of IL-10 which suppressed antigen-specific CD4+ Th2 cell proliferation and increased expression of IgG4 (31).

This recent research indicates IgG4 is a marker of inflammation, not the cause of ISD. Zen et al examined pancreas and biliary tissue affected by an autoimmune process (now called ISD), primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) or primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) regarding cytokine production and regulatory T (Treg) cell involvement. They found that the tissue affected by ISD had significantly higher ratios of specific Th2-producing cytokines including IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 compared to Th1 cytokine IFN γ (32). Further, ISD tissue had an increase in CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells which induce IL-10 to halt the immune reaction that generates inflammation. They concluded ISD is characterized by Th2-induced inflammation and counteracted with Treg cells.

Despite these recent findings, it remains unclear if the inflammation in ISD is due to a self-antigen (i.e. an autoimmune process) or an unknown allergen. In general, ISD has no specific autoantibody that has been associated with an autoimmune reaction and the reactions that have been identified are likely markers of tissue injury. However, AIP has been linked to certain autoantigens including carbonic anhydrase, lactoferrin, pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor and trysinogens (38). The dramatic, rapid response to steroids with few relapses in the disease also favors a hypersensitive/allergic reaction. While other subclasses of IgG participate in both type II (antibody-dependent) and type III (immune complex disease) forms of hypersensitivity, as mentioned previously IgG4 does not form immune complexes, thus it seems it would be dominated by a type I hypersensitivity (33). However, this type of hypersensitivity is specifically dominated by IgE-triggered mast cells with less involvement of Th2. Therefore ISD appears to be more consistent with type IV hypersensitivity, the delayed form. ISD is homogenous with subtype IVb that involves Th2-directed cytokines IL-5, IL-4, IL-13. Type I hypersensitivity is not a response to a self-antigen, like it is in type II and III hypersensitivity, but rather is an immune reaction dominated by Th2 cells. This is the same type of cell repetitively identified in ISD and classically involved in the allergic disorders such as allergic rhinitis and chronic asthma (12, 34, 35).

Also arguing against autoimmunity is the predisposition for elderly men, contrasting most autoimmune disease diagnosed in young females. Extrapancreatic ISD appears to favor males. The exception is ISD of the head and neck, in which the female-male ratio is even. Interestingly because this form of ISD overlaps with other sclerosing diseases such as Mikulicz’s disease and Sjogren ’s syndrome (SS), it is thought many of these patients may have been misdiagnosed and have ISD. Men with SS are extremely rare however in one review half of those with this disease actually had ISD upon re-examination (10, 25).

One well-documented exception to the allergen-induced cause of ISD is seen in some cases of ISD that have had immune complex deposits identified in the basement membranes of pancreatic acini and renal tubules, which is a form of type III hypersensitivity (35). This finding would support autoimmunity and implies the disease occurs from tissue injury related to self antigens that induce a cytokine response. The cytokines induced by Th2 cells and naïve regulatory T cells contribute to the stimulation in IgG4 production and lead to the sclerosing response, however it remains unknown what this process is in response to (9, 19, 32). Clearly a specific antigen would need to be identified before the disease is definitively classified.

IgG4’s pathologic role in ISD remains unclear, as does the use of serum IgG4 levels in diagnosis of ISD. Several studies have documented that the level of IgG4 varies significantly in healthy individuals, ranging from 1 - 1.4 µg/ml, but is elevated in about 5% and may even be as high as 2 mg/ml (37). The sensitivity and specificity of using serum IgG4 levels to differentiate AIP from other pancreatic disease, such as malignancy, varies depending on the study and diagnostic criteria used, ranging from 67-97% and 89-100% respectively (38). Although clearly elevated in a majority of patients with AIP (noted up to 80%), serum IgG4 can still be elevated in as many as 10% of pancreatic cancer patients, as recently reported by Sah and Chari (38). These statistics carry over to extrapancreatic ISD as well. In a review by Zen (10) of 114 cases diagnosed with ISD involving any organ, only 86% of patients had elevated IgG4 levels, with 2.6% of patients having an underlying malignancy of the affected organ.

Pathology

There are four known pulmonary histology patterns in ISD (7, 10, 12, 18). The solid nodular pattern presents as sclerosing inflammation in the hilar large bronchus walls and distinctly involves bronchial glands as well. The lymphoplasmacytic infiltration occurs in the alveoli around and away from the nodular lesions. The bronchovascular pattern involves inflammatory infiltration of the pulmonary connective tissue (bronchovascular bundles, alveolar interstitium, interlobular septa, and pleura). The alveolar interstitial pattern involves sclerosing inflammation of only the interstitium, similar to a nonspecific interstitial pneumonia pattern.

The histologic presentations specific to pulmonary ISD have both an overlap and slight variation compared to both its pancreatic and extrapancreatic relatives. Like all involved organs with ISD, pulmonary lesions have a diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltration. Another characteristic feature seen in all forms of ISD is obliterative phlebitis, the destruction of veins from sclerosing inflammation (18, 19). However, obliterative arteritis is unique to pulmonary ISD, which is rarely, if ever, seen in pancreatic or other extrapancreatic ISD (10, 18, 20).

Diagnosis

Accurate diagnosis of ISD is essential. Once malignancy is ruled out, a primary concern in any organ presenting with a mass, proper treatment must ensue to prevent permanent organ damage from disease-induced sclerosis. Diabetes mellitus may occur with AIP, obstructed pancreaticobiliary tree can cause portal hypertension and cirrhosis, affected retroperitoneum can become permanently scarred, and ISD of the kidney may result in renal failure and life-long dialysis (1, 14, 18, 24). Although there have been reports of spontaneous remission in untreated AIP, these patients were noted to have evidence of a much lower disease burden on lab and imaging (39).

The inflammatory sclerosis induced by IgG4+ lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration is the primary characteristic feature in diagnosing ISD. Because the disease presents with histopathological differences depending on the organ system affected, there is no single feature used to confirm the diagnosis. This has also made it difficult to develop unified diagnostic criteria. Several groups and countries have acquired their own diagnostic criteria which mostly overlap and primarily have only slight variations in defining the histology. Diagnostic criteria are constantly being revised as new research emerges. A majority of diagnostic criteria require an absolute number of IgG4+ cells per HPF, a ratio of IgG4+ cells per IgG+ cells, and an elevated serum IgG4 (18). Recently the Japan College of Rheumatology proposed an organ-based algorithm to diagnose the likelihood of ISD and takes into consideration the disease presentation of the involved organ(s), histopathology and serum IgG4 levels (40). Additional diagnostic considerations not incorporated or required in Japan’s criteria may include imaging and a rapid response to steroid treatment (9). Regardless of the disparity over precisely defining the histological required minimum number of IgG4+ cells, it is clear that the higher the number, the more sensitive and specific the diagnosis (18).

Pulmonary ISD was initially identified as an interstitial pneumonia and later as a pseudotumor (6, 39). Currently it has presented in multiple radiographic patterns including solid parenchymal nodules (mass-like), bronchovascular pattern (often mistaken for sarcoidosis), round-shaped ground-glass opacification (similar to bronchioalveolar carcinoma), alveolar interstitial pattern (presenting with bronchiectasis or honeycombing), areas of diffuse ground-glass opacification (mimicking nonspecific interstitial pneumonia), and air-space consolidation (comparable to organizing pneumonia) (1, 41). Additionally, ISD has been found in the mediastinum, pleura, interstitium of all lung zones and main airways. Patients may present with a single feature or have several pulmonary variations (9, 13, 42).

Treatment

Once studies showed AIP treated with corticosteroids went into remission quicker than untreated disease and were able to reverse affected organ symptoms like diabetes, they became standard therapy for all forms of ISD (9, 43). Steroid dosing for ISD is undefined like most steroid treatment in pulmonary (or any other inflammatory disease for that matter) and ranges from 0.6mg/kg to 10 mg/day (26, 43). The length of treatment also varies with the Mayo Clinic tapering off all therapy at 11 weeks and Japanese centers, who report lower relapse rates, treating as long as 6 months followed by a slow-dose maintenance steroid for up to 3 years (44). Most patients have reversal of the abnormality seen on imaging and many will have a decrease or even normalization of serum IgG4 within 2 weeks of initiating therapy. Reports of relapse have been seen in up to 25% of patients and ISD can also occur in a completely separate organ system than the first, as seen in our patient. A failure response is difficult to define because serum IgG4 often remains elevated despite resolution of symptoms and imaging abnormalities and again, patients may be asymptomatic or have disease recur in new primary organ systems (43). Patients who continue to have evidence of persistent disease after steroids are tapered off have had success with additional immunosuppressants. The Mayo Clinic has accomplished remission with the use of azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil in patients with AIP in addition to case reports using rituximab, which deplete IgG4 B lymphocytes, and the anti-plasmacyte medication, bortezomib (45).

Using IgG4 levels to monitor ISD response to steroids has been shown to be helpful in several studies (5, 6, 8, 12, 13, 18, 41, 46, 47), especially since patients may have little to no symptoms of the organ affected by ISD. Elevated serum levels have been proven helpful in correlating disease burden, meaning a higher level indicates increased single or multisystem organ involvement (48). Unfortunately many patients in these studies, despite treatment, continued to have elevated levels (13, 38, 43). Empiric steroid trials have been found to decrease false positive elevated IgG4 levels so using a decline in serum IgG4 after initiating steroid treatment is also not a consistently reliable tool to track disease progress (38). Also the serum IgG4 level may not even be elevated and appear normal if the initial patient presentation is during the earlier phase of the disease before IgG4 proliferates (37, 38). Trending IgG4 levels for evidence of disease relapse has also been suggested however studies involving patients treated with steroids for AIP found that relapse still occurs in 10% of patients whose IgG4 level did return to normal compared to 30% of patients who remained elevated (44). Unfortunately the amount of disease relapse in ISD is underestimated as most case studies do not have long term follow up and IgG4 is frequently not reported nor is it rechecked unless the patient presents with recurring or new symptoms. Also, these results were limited to pancreatic ISD so more research is required to determine if these statistics are similar regardless of affected organ.

Summary

ISD remains exceedingly rare and unfamiliar, particularly extrapancreatic disease. This is one of only a handful of reported patients with separate presentations of IgG4 pulmonary disease and recurring IgG4 related biliary sclerosis and pancreatitis. Because of the intricate and perplexing pathogenesis, overlapping organ systems and wide variation in disease presentation, ISD in its entirety remains undefined. Accurate identification of ISD is critical to avoid permanent organ damage especially since treatment is nearly always successful with corticosteroids. As recognition and awareness of this disease grows, development of standard diagnostic criteria and treatment plans are needed.

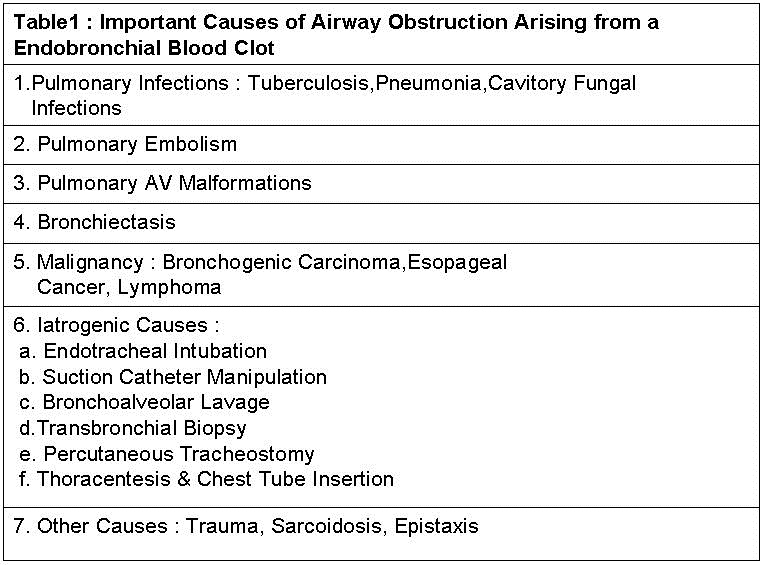

References

-

Vlachou PA, Khalili K, Jang HJ, Fischer S, Hirschfield GM, Kim TK. IgG4-related sclerosing disease: autoimmune pancreatitis and extrapancreatic manifestations. Radiographics. 2011;31(5):1379-402.

[CrossRef] [Pubmed]

-

Borszewski J, Pancewicz-Olszewska W. A case of obstructive jaundice caused by chronic inflammation of the head of the pancreas. Pediatr Pol. 1959;34:835-8.

[PubMed]

-

Sarles H, Sarles JC, Muratore R, Guien C. Chronic inflammatory sclerosis of the pancreas--an autonomous pancreatic disease? Am J Dig Dis. 1961;6:688-98. [CrossRef] [Pubmed]

-

Bank S, Novis BH, Petersen E, Dowdle E, Marks IN. Serum immunoglobulins in calcific pancreatitis. Gut. 1973;14(9):723-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Hamano H, Kawa S, Horiuchi A, Unno H, Furuya N, Akamatsu T, Fukushima M, Nikaido T, Nakayama K, Usuda N, Kiyosawa K. High serum IgG4 concentrations in patients with sclerosing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2001; 8:344(10):732-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Taniguchi T, Ko M, Seko S, Nishida O, Inoue F, Kobayashi H, Saiga T, Okamoto M, Fukuse T. Interstitial pneumonia associated with autoimmune pancreatitis. Gut. 2004;53(5):770.

[PubMed]

-

Bateman AC, Deheragoda MG. IgG4-related systemic sclerosing disease - an emerging and under-diagnosed condition. Histopathology. 2009;55(4):373-83.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Shigemitsu H, Koss MN. IgG4-related interstitial lung disease: a new and evolving concept. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2009;15(5):513-6.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Ryu JH, Sekiguchi H, Yi ES. Pulmonary manifestations of immunoglobulin G4-related sclerosing disease. Eur Respir J. 2012;39(1):180-6.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Zen Y, Nakanuma Y. IgG4-related disease: a cross-sectional study of 114 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(12):1812-9.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Khosroshahi A, Stone JH. A clinical overview of IgG4-related systemic disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23(1):57-66.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Zen Y, Inoue D, Kitao A, Onodera M, Abo H, Miyayama S, Gabata T, Matsui O, Nakanuma Y. IgG4-related lung and pleural disease: a clinicopathologic study of 21 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(12):1886-93.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Ito M, Yasuo M, Yamamoto H, Tsushima K, Tanabe T, Yokoyama T, Hamano H, Kawa S, Uehara T, Honda T, Kawakami S, Kubo K.Central airway stenosis in a patient with autoimmune pancreatitis. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(3):680-3.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Cornell LD. IgG4-related tubulointerstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 2010;78(10):951-3.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Sprangers B, Lioen P, Meijers B, Lerut E, Meersschaert J, Blockmans D, Claes K. The many faces of Merlin: IgG4-associated pulmonary-renal disease. Chest. 2011;140(3):791-4.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Imai T, Yumura W, Takemoto F, Kotoda A, Imai R, Inoue M, Hironaka M, Muto S, Kusano E. A case of IgG4-related tubulointerstitial nephritis with left hydronephrosis after a remission of urinary tract tuberculosis. Rheumatol Int. 2012 Jan 5.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Nishi S, Imai N, Yoshida K, Ito Y, Saeki T. Clinicopathological findings of immunoglobulin G4-related kidney disease. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2011;15(6):810-9.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Shrestha B, Sekiguchi H, Colby TV, Graziano P, Aubry MC, Smyrk TC, Feldman AL, Cornell LD, Ryu JH, Chari ST, Dueck AC, Yi ES. Distinctive pulmonary histopathology with increased IgG4-positive plasma cells in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis: report of 6 and 12 cases with similar histopathology. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(10):1450-62.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Cheuk W, Chan JK. IgG4-related sclerosing disease: a critical appraisal of an evolving clinicopathologic entity. Adv Anat Pathol. 2010;17(5):303-32.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Deshpande V, Gupta R, Sainani N, Sahani DV, Virk R, Ferrone C, Khosroshahi A, Stone JH, Lauwers GY. Subclassification of autoimmune pancreatitis: a histologic classification with clinical significance. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(1):26-35.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Kamisawa T, Anjiki H, Egawa N, Kubota N. Allergic manifestations in autoimmune pancreatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21(10):1136-39.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Zen Y, Bogdanos DP, Kawa S. Type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;7;6:82.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Chari ST, Takahashi N, Levy MJ, Smyrk TC, Clain JE, Pearson RK, Petersen BT, Topazian MA, Vege SS. A diagnostic strategy to distinguish autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(10):1097-103.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Taniguchi T, Ko M, Seko S, Nishida O, Inoue F, Kobayashi H, Saiga T, Okamoto M, Fukuse T. Interstitial pneumonia associated with autoimmune pancreatitis. Gut. 2004;53(5):770.

[PubMed]

-

Masaki Y, Dong L, Kurose N, Kitagawa K, Morikawa Y, Yamamoto M, Takahashi H, Shinomura Y, Imai K, Saeki T, Azumi A, Nakada S, Sugiyama E, Matsui S, Origuchi T, Nishiyama S, Nishimori I, Nojima T, Yamada K, Kawano M, Zen Y, Kaneko M, Miyazaki K, Tsubota K, Eguchi K, Tomoda K, Sawaki T, Kawanami T, Tanaka M, Fukushima T, Sugai S, Umehara H. Proposal for a new clinical entity, IgG4-positive multiorgan lymphoproliferative syndrome: analysis of 64 cases of IgG4-related disorders. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(8):1310-5v.

[CrossRef] [PubMed[

-

Umeda M, Fujikawa K, Origuchi T, Tsukada T, Kondo A, Tomari S, Inoue Y, Soda H, Nakamura H, Matsui S, Kawakami A. A case of IgG4-related pulmonary disease with rapid improvement. Mod Rheumatol. 2012;22(6):919-23.

[PubMed]

-

van der Neut Kolfschoten M, Schuurman J, Losen M, Bleeker WK, Martínez-Martínez P, Vermeulen E, den Bleker TH, Wiegman L, Vink T, Aarden LA, De Baets MH, van de Winkel JG, Aalberse RC, Parren PW. Anti-inflammatory activity of human IgG4 antibodies by dynamic Fab arm exchange. Science. 200714;317(5844):1554-7.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Berger A.Th1 and Th2 responses: what are they? BMJ. 2000;321(7258):424.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Satoguina JS, Weyand E, Larbi J, Hoerauf A. T regulatory-1 cells induce IgG4 production by B cells: role of IL-10. J Immunol. 2005;15;174(8):4718-26.

[PubMed]

-

Jeannin P, Lecoanet S, Delneste Y, Gauchat JF, Bonnefoy JY. IgE versus IgG4 production can be differentially regulated by IL-10. J Immunol. 1998;160(7):3555-61.

[PubMed]

-

van de Veen W, Stanic B, Yaman G, Wawrzyniak M, Söllner S, Akdis DG, Rückert B, Akdis CA, Akdis M. IgG4 production is confined to human IL-10-producing regulatory B cells that suppress antigen-specific immune responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(4):1204-12.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Zen Y, Fujii T, Harada K, Kawano M, Yamada K, Takahira M, Nakanuma Y. Th2 and regulatory immune reactions are increased in immunoglobin G4-related sclerosing pancreatitis and cholangitis. Hepatology. 2007;45(6):1538-46.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Gell PGH, Coombs RRA, eds. Clinical Aspects of Immunology. 1st ed. Oxford, England: Blackwell; 1963.

-

-

Ito S, Ko SB, Morioka M, Imaizumi K, Kondo M, Mizuno N, Hasegawa Y. Three cases of bronchial asthma preceding IgG4-related autoimmune pancreatitis. Allergol Int. 2012;61(1):171-4.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Deshpande V, Chicano S, Finkelberg D, Selig MK, Mino-Kenudson M, Brugge WR, Colvin RB, Lauwers GY. Autoimmune pancreatitis: a systemic immune complex mediated disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30(12):1537-45. Erratum in: Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(2):328.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Nirula A, Glaser SM, Kalled SL, Taylor FR. What is IgG4? A review of the biology of a unique immunoglobulin subtype. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23(1):119-24.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Sah RP, Chari ST. Serological issues in IgG4-related systemic disease and autoimmune pancreatitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011; 23(1):108-13.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Wakabayashi T, Kawaura Y, Satomura Y, Watanabe H, Motoo Y, Sawabu N. Long-term prognosis of duct-narrowing chronic pancreatitis: strategy for steroid treatment. Pancreas. 2005;30(1):31-9.

[PubMed]

-

Umehara H, Okazaki K, Masaki Y, Kawano M, Yamamoto M, Saeki T, Matsui S, Yoshino T, Nakamura S, Kawa S, Hamano H, Kamisawa T, Shimosegawa T, Shimatsu A, Nakamura S, Ito T, Notohara K, Sumida T, Tanaka Y, Mimori T, Chiba T, Mishima M, Hibi T, Tsubouchi H, Inui K, Ohara H. Comprehensive diagnostic criteria for IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD), 2011. Mod Rheumatol. 2012;22(1):21-30.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Inoue D, Zen Y, Abo H, Gabata T, Demachi H, Kobayashi T, Yoshikawa J, Miyayama S, Yasui M, Nakanuma Y, Matsui O.Immunoglobulin G4-related lung disease: CT findings with pathologic correlations. Radiology. 2009;251(1):260-70.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Kobayashi H, Shimokawaji T, Kanoh S, Motoyoshi K, Aida S. IgG4-positive pulmonary disease. J Thorac Imaging. 2007;22(4):360-2.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Khosroshahi A, Stone JH. Treatment approaches to IgG4-related systemic disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23(1):67-71.

. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Kamisawa T, Okamoto A, Wakabayashi T, Watanabe H, Sawabu N. Appropriate steroid therapy for autoimmune pancreatitis based on long-term outcome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(5):609-13.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Khan ML, Colby TV, Viggiano RW, Fonseca R. Treatment with bortezomib of a patient having hyper IgG4 disease. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2010;10(3):217-9.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Hirano K, Kawabe T, Komatsu Y, Matsubara S, Togawa O, Arizumi T, Yamamoto N, Nakai Y, Sasahira N, Tsujino T, Toda N, Isayama H, Tada M, Omata M. High-rate pulmonary involvement in autoimmune pancreatitis. Intern Med J. 2006;36(1):58-61.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Zen Y, Kitagawa S, Minato H, Kurumaya H, Katayanagi K, Masuda S, Niwa H, Fujimura M, Nakanuma Y. IgG4-positive plasma cells in inflammatory pseudotumor (plasma cell granuloma) of the lung. Hum Pathol. 2005;36(7):710-7.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Hamano H, Arakura N, Muraki T, Ozaki Y, Kiyosawa K, Kawa S. Prevalence and distribution of extrapancreatic lesions complicating autoimmune pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41(12):1197-205.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

Reference as: Hurley JR, Leslie KO. IgG4-related systemic disease of the pancreas with involvement of the lung: a case report and literature review. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2013;7(2):117-30. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc039-13 PDF

Saturday, September 14, 2013 at 9:49AM

Saturday, September 14, 2013 at 9:49AM