On 4-23-12 the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Inspector General (OIG) issued a report of the accuracy of the Veterans Healthcare Administration (VHA) wait times for mental health services. The report found that “VHA does not have a reliable and accurate method of determining whether they are providing patients timely access to mental health care services. VHA did not provide first-time patients with timely mental health evaluations and existing patients often waited more than 14 days past their desired date of care for their treatment appointment. As a result, performance measures used to report patient’s access to mental health care do not depict the true picture of a patient’s waiting time to see a mental health provider.” (1). The OIG made several recommendations and the VA administration quickly concurred with these recommendations. Only four days earlier the VA announced plans to hire 1900 new mental health staff (2).

This sounded familiar and so a quick search on the internet revealed that about a year ago the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit issued a scathing ruling saying that the VA had failed to provide adequate mental health services to Veterans (3). A quick review of the Office of Inspector General’s website revealed multiple instances of similar findings dating back to at least 2002 (4-7). In each instance, unreliable data regarding wait times was cited, VA administration agreed, and no or inadequate action was taken.

Inadequate Numbers of Providers

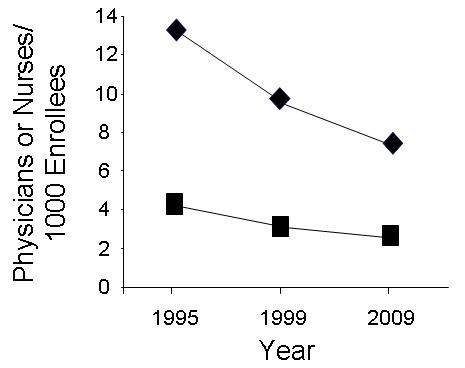

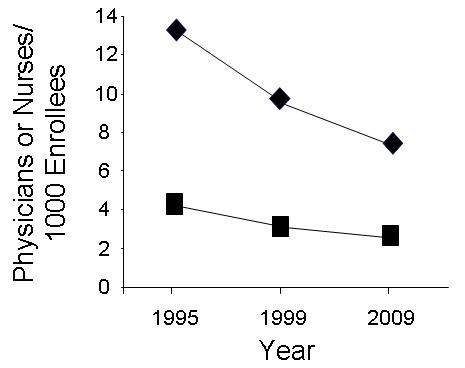

One of the problems is that inadequate numbers of clinical physicians and nurses are employed by the VA to care for the patients. In his “Prescription for Change”, Dr. Ken Kizer, then VA Undersecretary for Health, made bold changes to the VA system in the mid 1990’s (8). Kizer cut the numbers of hospitals but also the numbers of clinicians while the numbers of patients increased (9). The result was a marked drop in the number of physicians and nurses per VA enrollee (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Nurses (squares) and physicians (diamonds) per 1000 VA enrollees for selected years (10,11).

This data is consistent with a 2011 VA survey that asked VA mental health professionals whether their medical center had adequate mental health staff to meet current veteran demands for care; 71 percent responded no. According to the OIG, VHA’s greatest challenge has been to hire psychiatrists (1). Three of the four sites visited by the OIG had vacant psychiatry positions. One site was trying to replace three psychiatrists who left in the past year. This despite psychiatrists being one of the lowest paid of the medical specialties (12). The VA already has about 1,500 vacancies in mental-health specialties. This prompted Sen. Patty Murray, Chairman of the Senate Committee on Veterans Affairs to ask about the new positions, "How are you going to ensure that 1,600 positions ... don't become 1,600 vacancies?" (13).

Administrative Bonuses

A second problem not identified by the OIG is administrative bonuses. Since 1996, wait times have been one of the hospital administrators’ performance measures on which administrative bonuses are based. According to the OIG these numbers are unreliable and frequently “gamed” (1,4-7). This includes directions from VA supervisors to enter incorrect data shortening wait times (4-7).

At a hearing before the Senate Committee on Veterans' Affairs Linda Halliday from the VA OIG said "They need a culture change. They need to hold facility directors accountable for integrity of the data." (13). VA "greatly distorted" the waiting time for appointments, Halliday said, enabling the department to claim that 95 percent of first-time patients received an evaluation within 14 days when, in reality, fewer than half were seen in that time. Nicholas Tolentino, a former mental-health administrative officer at the VA Medical Center in Manchester, N.H., told the committee that managers pressed the staff to see as many veterans as possible while providing the most minimal services possible. "Ultimately, I could not continue to work at a facility where the well-being of our patients seemed secondary to making the numbers look good," he said.

Although falsifying wait times has been known for years, there has been inadequate action to correct the practice according to the VA OIG. Sen. Murray said the findings show a "rampant gaming of the system." (13). This should not be surprising. Clerical personnel who file the data have their evaluations, and in many cases pay, determined by supervisors who financially benefit from a report of shorter wait times. There appears no apparent penalty for filing falsified data. If penalties did exist, it seems likely that the clerks or clinicians would be the ones to shoulder the blame.

The Current System is Ineffective

A repeated pattern of the OIG being called to look at wait times, stating they are false, making recommendations, the VA concurring, and nothing being done has been going on for years (1, 3-7). Based on these previous experiences, the VA will likely be unable to hire the numbers of clinicians needed and wait times will continue to be unacceptably long but will be “gamed” to “make the numbers look good”. Pressure will be placed on the remaining clinicians to do more with less. Some will become frustrated and leave the VA. The administrators will continue to receive bonuses for inaccurate short wait times. If past events hold true, in 2-5 years another VA OIG report will be requested. It will restate that the VA falsified the wait times. This will be followed by a brief outcry, but nothing will be done.

The VA OIG apparently has no real power and the VA administrators have no real oversight. The VA OIG continues to make recommendations regarding additional administrative oversight which smacks of putting the fox in charge of the hen house. Furthermore, the ever increasing numbers of administrators likely rob the clinical resources necessary to care for the patients. Decreased clinical expenses have been shown to increase standardized mortality rates, in other words, hiring more administrators at the expense of clinicians likely contributes to excess deaths (14). Although this might seem obvious, when the decrease of physicians and nurses in the VA began in the mid 1990’s there seemed little questioning that the reduction was an “improvement” in care.

Traditional measures such as mortality, morbidity, etc. are slow to change and difficult to measure. In order to demonstrate an “improvement” in care what was done was to replace outcome measures with process measures. Process measures assess the frequency that an intervention is performed. The problem appears that poor process measures were chosen. The measures included many ineffective measures such as vaccination with the 23 polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine in adult patients and discharge instructions including advice to quit smoking at hospital discharge (15). Many were based on opinion or poorly done trials, and when closely examined, were not associated with better outcomes. Most of the “improvement” appeared to occur in performance of these ineffective measures. However, these measures appeared to be quite popular with the administrators who were paid bonuses for their performance.

Root Causes of the Problems

The root causes go back to Kizer’s Prescription for Change. The VA decreased the numbers of clinicians, but especially specialists, while increasing the numbers of administrators and patients. The result has been what we observe now. Specialists such as psychiatrists are in short supply. They were often replaced by a cadre of physician extenders more intent on satisfying a checklist of ineffective process measures rather than providing real help to the patient. Waiting times lengthened and the administrative solution was cover up the problem by lying about the data.

VA medical centers are now usually run by administrators with no real medical experience. From the director down through their administrative chain of command, many are insufficiently medically trained to supervise a medical center. These administrators could not be expected to make good administrative decisions especially when clinicians have no meaningful input (10).

The present system is not transparent. My colleagues and I had to go through a FOIA request to obtain data on the numbers of physicians and nurses presented above. Even when data is known, the integrity of the data may be called into question as illustrated by the data with the wait times.

The falsification of the wait times illustrates the lack of effective oversight. VA administration appears to be the problem and hiring more administrators who report to the same administrators will not solve the problem as suggested by the VA OIG (3-7). What is needed is a system where problems such as alteration of wait times can be identified on the local level and quickly corrected.

Solutions to the Problems

The first and most important solution is to provide meaningful oversight by at the local level by someone knowledgeable in healthcare. Currently, no system is in place to assure that administrators are accountable. Despite concurring with the multitude of VA OIG’s recommendations, VA central office and the Veterans Integrated Service Networks have not been effective at correcting the problem of falsified data. In fact, their bonuses also depend on the data looking good. Locally, there exists a system of patient advocates and compliance officers but they report to the same administrators that they should be overseeing. The present system is not working. Therefore, I propose a new solution, the concept of the physician ombudsman. The ombudsman would be answerable to the VA OIG’s office. The various compliance officers, patient advocates, etc. should be reassigned to work for the ombudsman and not for the very people that they should be scrutinizing.

The physician ombudsman should be a part-time clinician, say 20% at a minimum. The latter is important in maintaining local clinical knowledge and identifying falsified clinical data. One of the faults of the present VA OIG system is that when they look at a complaint, they seem to have difficulty in identifying the source of the problem (16). Local knowledge would likely help and clinical experience would be invaluable. For example, it would be hard to say waiting times are short when the clinician ombudsman has difficulty referring a patient to a specialist at the VA or even booking a new or returning patient into their own clinic.

The overseeing ombudsman needs to have real oversight power, otherwise we have a repeat of the present system where problems are identified but nothing is done. Administrators should be privileged similar to clinicians. Administrators should undergo credentialing and review. This should be done by the physician ombudsman’s office. Furthermore, the physician ombudsman should have the capacity to suspend administrative privileges and decisions that are potentially dangerous. For example, cutting the nursing staffing to dangerous levels in order to balance a budget might be an example of a situation where an ombudsman could rescind the action.

The paying of administrative bonuses for clinical work done by clinicians should stop. Administrators do not have the necessary medical training to supervise clinicians, and furthermore, do nothing to improve efficiency or clinically benefit Veterans (14). The present system only encourages further expansion of an already bloated administration (17). Administrators hire more administrators to reduce their workload. However, since they now supervise more people, they argue for an increase in pay. If a bonus must be paid, why not pay for something over which the administrators have real control, such as administrative efficiency (18). Perhaps this will stop the spiraling administrative costs that have been occurring in healthcare (17).

These suggestions are only some of the steps that could be taken to improve the chronic falsification of data by administrators with a financial conflict of interest. The present system appears to be ineffective and unlikely to change in the absence of action outside the VA. Otherwise, the repeating cycle of the OIG being called to look at wait times, noting that they are gamed, and nothing being done will continue.

Richard A. Robbins, M.D.*

Editor, Southwest Journal of Pulmonary

and Critical Care

References

- http://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-12-00900-168.pdf (accessed 4-26-12).

- http://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=2302 (accessed 4-26-12).

- http://www.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/opinions/2011/07/12/08-16728.pdf (accessed 4-26-12).

- http://www.va.gov/oig/52/reports/2003/VAOIG-02-02129-95.pdf (accessed 4-26-12).

- http://www.va.gov/oig/54/reports/VAOIG-05-03028-145.pdf (accessed 4-26-12).

- http://www.va.gov/oig/54/reports/VAOIG-05-03028-145.pdf (accessed 4-26-12).

- http://www.va.gov/oig/52/reports/2007/VAOIG-07-00616-199.pdf (accessed 4-26-12).

- www.va.gov/HEALTHPOLICYPLANNING/rxweb.pdf (accessed 4-26-12).

- http://veterans.house.gov/107th-congress-hearing-archives (accessed 3/18/2012).

- Robbins RA. Profiles in medical courage: of mice, maggots and Steve Klotz. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2012;4:71-7.

- Robbins RA. Unpublished observations obtained from the Department of Veterans Affairs by FOIA request.

- http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/compensation/2012/psychiatry (accessed 4-26-12).

- http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/localnews/2018071724_mentalhealth26.html (accessed 4-26-12).

- Robbins RA, Gerkin R, Singarajah CU. Correlation between patient outcomes and clinical costs in the VA healthcare system. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2012;4:94-100.

- Robbins RA, Klotz SA. Quality of care in U.S. hospitals. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1860-1 [letter].

- Robbins RA. Mismanagement at the VA: where's the problem? Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2011;3:151-3.

- Woolhandler S, Campbell T, Himmelstein DU. Health care administration in the United States and Canada: micromanagement, macro costs. Int J Health Serv 2004;34:65-78.

- Gao J, Moran E, Almenoff PL, Render ML, Campbell J, Jha AK. Variations in efficiency and the relationship to quality of care in the Veterans health system. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:655-63.

*The author is a former VA physician who retired July 2, 2011 after 31 years.

The opinions expressed in this editorial are the opinions of the author and not necessarily the opinions of the Southwest Journal of Pulmonary and Critical Care or the Arizona Thoracic Society.

Reference as: Robbins RA. VA administrators gaming the system. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2012;4:149-54. (Click here for a PDF version of the editorial)

Saturday, June 9, 2012 at 10:21AM

Saturday, June 9, 2012 at 10:21AM