VA Administrators Breathe a Sigh of Relief

Sunday, June 8, 2014 at 8:52PM

Sunday, June 8, 2014 at 8:52PM On May 30, Eric Shinseki, the Secretary for Veterans Affairs (VA), resigned under pressure amidst a growing scandal regarding falsification of patient wait times at nearly 40 VA medical centers. Before leaving office Shinseki fired Sharon Helman, the former hospital director at the Phoenix VA, where the story first broke, along with her deputy and another unnamed administrator. In addition, Susan Bowers, director of VA Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) 18 and Helman’s boss, resigned. Robert Petzel, undersecretary for the Veterans Health Administration (VHA, head of the VA hospitals and clinics), had resigned earlier. You could hear the sigh of relief from the VA administrators.

With their bosses resigning left and right, the VA leadership in shambles and the reputation of the VA soiled for many years to come, why are the VA administrators relieved? The simple answer is that nothing has really changed. There for a moment it looked like real reform might happen. Even President Obama in announcing Shinseki's resignation said the "There is a need for a change in culture..." (1). Shinseki’s resignation would indicate that any action to change the culture is unlikely. Sure a few administrators, like Helman, will lose their jobs, perhaps a few patients will get outsourced to private practioners, but nothing is being done or proposed to change the VA culture. A new interim VA secretary was named and his tenure is likely to be lengthy since no confirmation appears to go unchallenged in the US Congress, and who would want the job?

I was at the VA, when then undersecretary for VHA, Kenneth Kizer, made the fundamental change that resulted in the present mess. Kizer had come to the VA with a program he called the “prescription for change” (2). Indeed, Kizer made several changes but the one that really counted was that the chiefs of staff, doctors who ran the medical services in VA hospitals, were replaced by the head of the Medical Administration Service, usually a business person. This made the VA director the monarch over their own little kingdom, and we all know “it’s good to be the king”. Furthermore, we all know that power corrupts and now with absolute power, the VA director was absolutely corrupted. The hospital directors eliminated any sources of potential opposition. Physicians who did not “play ball” could suddenly find themselves as a target of an investigation (3). After being found guilty by a kangaroo court, their names would be turned over to the National Practioner Databank as bad doctors making it difficult to find a job outside the VA. Those cooperative physicians were rewarded, often for limiting the care of patients. In other words, putting the VA administrators’ interests before the patients’ (4). Lastly, the long-standing relationship with the Nation’s medical schools was destroyed (remember VA dean’s hospitals?). It was argued that the medical schools used the VA to serve their needs. Although this had some truth, it is part of the two-way street that makes cooperation possible. No VA administrator wanted a bunch of doctors and academics telling them what to do.

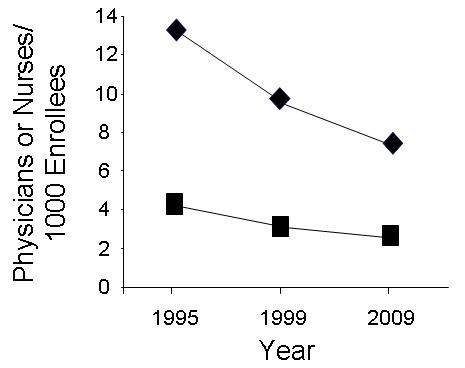

After eliminating any possible oversight from the physicians or the medical schools, an insulating administrative layer had to be placed between the hospitals and VA central office. Therefore, the Veterans Integrated Service Networks or VISNs, were created. Although ostensibly to improve oversight and efficiency (2), only in Washington would they believe that another layer of bureaucracy would do either. As more and more patients were packed into the system, the numbers of physicians and nurses decreased (5). Not surprisingly, wait times became longer and there was no alternative but to hide the truth. The administrators, the VISNs and VA Central office were all complicit in these lies. Their bonuses depended on it and even when it was discovered by the VA Office of Inspector General (VAOIG) nothing was done.

Congress, who supposedly also provides oversight, was swift to propose action that does not change the VA culture and accomplish little. In this election year Congressional cries to throw those VA bums out have been consistent and loud. However, plenty of clues were available to know that the wait time data was false. First, the concept that you can cut the numbers of physicians and nurses and improve wait times defies common sense. Second, the VAOIG had repeatedly reported that wait times were being falsified. Helman had already been accused of this when she was the director at the Spokane VA (6). This week the Senate passed a bill allowing veterans to see private doctors outside the VA system if they experience long wait times or live more than 40 miles from a VA facility; make it easier to fire VA officials; construct 26 new VA medical facilities and use $500 million in unobligated VA funds to hire additional VA doctors and nurses (7). The VA already is able to do the first two, and as the present crisis illustrates, funds can be diverted away from healthcare. It seems likely this is exactly what will happen unless additional oversight is provided.

Kizer and Ashish Jha authored an editorial on this crisis in the New England Journal of Medicine this week (8). They made three recommendations:

- The VA should refocus on fewer measures that directly address what is most important to veteran patients and clinicians-especially outcome measures.

- Some of the resources supporting the central and network office bureaucracies could be redirected to bolster the number of caregivers.

- The VA needs to engage more with health care organizations and the general public.

All these recommendations are reasonable. Outcome measures, not process of care, should be measured (9). Paying bonuses to administrators for clinicians completing these process of care measures should stop. Many of these measures serve mostly to increase administrative bonuses and not improve patient care. By giving administrators supervisory authority over physicians, healthcare providers were forced to complete a seemingly endless checklists rather than serve the patients' interests.

Bureaucracies should be reduced. VA's central-office staff has grown from about 800 in the late 1990s to nearly 11,000 in 2012 (8). VISN offices have reflected this growth with over 4500 employees in 2012 (10). This diversion of funds away from healthcare is the source of the present problem.

The VA needs to re-engage with the medical schools and with its patients. Reestablishment of the Dean's Committee or other similar system that provides oversight of the VA hospital directors and administrators may be one method of achieving this oversight. The association of the medical schools with the VA served the VA well from the Second World War until the 1990s (11).

Poor pay and micromanagement of physicians to perform meaningless metrics makes primary care onerous. Appropriating funds might improve the salary discrepancy between the VA and the private sector but will not fix the micromanagement problem. The VA may find it difficult to recruit the needed physicians and nurses unless a more friendly work environment is created. How do we know that any appropriated money will be spent on healthcare providers and infrastructure unless additional oversight is put in place? Without oversight the VA positions will become VA vacancies and the VA hospitals will become administrative palaces. Local oversight by VA physicians, nurses and patients is one method of ensuring that appropriated monies are actually spent on healthcare.

VA health care is at a crossroads. New leadership can help the VA succeed but only if the administrative structure is fixed changing the VA culture. Until this occurs the same administrative monarchs will continue to rule their realms and nothing will really change.

Richard A. Robbins, MD*

Editor

Southwest Journal of Pulmonary and Critical Care

References

- Cohen T, Griffin D, Bronstein S, Black N. Shinseki resigns, but will that improve things at VA hospitals? CNN. May 31, 2014. Available at: http://www.cnn.com/2014/05/30/politics/va-hospitals-shinseki/ (accessed 6/7/14).

- Kizer KW. Prescription for change. March 1996. Available at: http://www.va.gov/HEALTHPOLICYPLANNING/rxweb.pdf (accessed 6/7/14).

- Wagner D. The doctor who launched the VA scandal. Arizona Republic. May 31, 2014. Available at: http://www.azcentral.com/longform/news/arizona/investigations/2014/05/31/va-scandal-whistleblower-sam-foote/9830057/ (accessed 6/7/14).

- Hsieh P. Three factors that corrupted VA health care and threaten the rest of American medicine. Forbes. May 30, 2014. Available at: http://www.forbes.com/sites/paulhsieh/2014/05/30/three-factors-that-corrupted-va-health-care/ (accessed 6/7/14).

- Robbins RA. VA administrators gaming the system. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2012;4:149-54. Available at: http://www.swjpcc.com/editorial/2012/5/5/va-administrators-gaming-the-system.html (accessed 6/7/14).

- Robbins RA. VA scandal widens. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2014;8(5):288-9. Available at: http://www.swjpcc.com/editorial/2014/5/26/va-scandal-widens.html (accessed 6/7/14).

- O'Keefe E. Senators reach bipartisan deal on bill to fix VA. Washington Post. June 5, 2014. Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/post-politics/wp/2014/06/05/senators-reach-bipartisan-deal-on-bill-to-fix-va/ (accessed 6/7/14).

- Kizer KW, Jha AK. Restoring trust in VA health care. N Engl J Med. 2014 Jun 4. [Epub ahead of print]. Available at: http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1406852 (accessed 6/7/14). [CrossRef]

- Robbins RA, Klotz SA. Quality of care in U.S. hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(17):1860-1. [CrossRef]

- VA Office of Inspector General. Audit of management control structures for veterans integrated service network offices. March 27, 2012. Available at: http://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-10-02888-129.pdf (accessed 6/7/14).

- VA policy memorandum no. 2: policy in association of veterans' hospitals with medical schools. January 30, 1946. Available at: http://www.va.gov/oaa/Archive/PolicyMemo2.pdf (accessed 6/7/14).

*The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, or California Thoracic Societies or the Mayo Clinic.

Refence as: Robbins RA. VA administrators breathe a sigh of relief. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2014;8(6):336-9. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc077-14 PDF