Richard A. Robbins, MD

Phoenix Pulmonary and Critical Care Research and Education Foundation

Gilbert, AZ USA

Abstract

Politicians and healthcare administrators have touted that under their leadership enormous strides have been made in the quality of healthcare. However, the question of how to measure quality remains ambiguous. To demonstrate improved quality that is meaningful to patients, outcomes such as life expectancy, mortality, and patient satisfaction must be validly and reliably measured. Dramatic improvements made in many of these patient outcomes through the twentieth century have not been sustained through the twenty-first. Most studies have shown no, or only modest improvements in the past several years, and at a considerable increase in cost. These data suggest that the rate of healthcare improvement is slowing and that many of the quality improvements touted have not been associated with improved outcomes.

Surrogate Markers

The most common measures of quality of healthcare come from Donabedian in 1966 (1). He identified two major foci for the measuring quality of care-outcome and process. Outcome referred to the condition of the patient and the effectiveness of healthcare including traditional outcome measures such as morbidity, mortality, length of stay, readmission, etc. Process of care represented an alternative approach which examined the process of care itself rather than its outcomes.

Beginning in the 1970’s the Joint Commission began to address healthcare quality by requiring hospitals to perform medical audits. However, the Joint Commission soon realized that the audit was “tedious, costly and nonproductive” (2). Efforts to meet audit requirements were too frequently “a matter of paper compliance, with heavy emphasis on data collection and few results that can be used for follow-up activities. In the shuffle of paperwork, hospitals often lost sight of the purpose of the evaluation study and, most important, whether change or improvement occurred as a result of audit”. Furthermore, survey findings and research indicated that audits had not resulted in improved patient care and clinical performance (2).

In response to the ineffectiveness of the audit and the call to improve healthcare, the Joint Commission introduced new quality assurance standards in 1980 which emphasized measurable improvement in process of care rather than outcomes. This approach proved popular with both regulatory agencies and healthcare investigators since it was easier and quicker to show improvement in process of care surrogate markers than outcomes.

Although there are many examples of the misapplication of these surrogate markers, one recent example of note is ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), a diagnosis without a clear definition. VAP guidelines issued by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement include elevation of the head of the bed, daily sedation vacation, daily readiness to wean or extubate, daily spontaneous breathing trial, peptic ulcer disease prophylaxis, and deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis. As early as 2011, the evidence basis of these guidelines was questioned (3). Furthermore, compliance with the guidelines had no influence on the incidence of VAP or inpatient mortality (3). Nevertheless, relying on self-reported hospital data the CDC published data touting declines in VAP rates of 71% and 62% in medical and surgical intensive care units, respectively, between 2006 and 2012 (4,5). However, Metersky and colleagues (6) reviewed Medicare Patient Safety Monitoring System (MPSMS) data on 86,000 critically ill patients between 2005 and 2013 and report that VAP rates remain unchanged since 2005.

Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP)

CMS’ own data might be interpreted as showing no improvement in quality. About 200 fewer hospitals will see bonuses from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) under the hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) program in 2017 than last year (7). The program affects some 3,000 hospitals and compares hospitals to other hospitals and its own performance over time.

The reduction in payments are “somewhat concerning,” according to Francois de Brantes, executive director of the Health Care Incentives Improvement Institute (7). One reason given was fewer hospitals were being rewarded, but another was hospitals' lack of movement in rankings. The HVBP contains inherent design flaws according to de Brantes. As a "tournament-style" program in which hospitals are stacked up against each other, they don't know how they'll perform until the very end of the tournament. "It's not as if you have a specific target," he said. "You could meet that target, but if everyone meets that target, you're still in the middle of the pack."

Although de Brantes point is well taken, another explanation might be that HVBP might reflect a declining performance in healthcare. If the HVBP program is to reward quality of care, fewer hospitals being rewarded logically indicates poorer care. As noted above, CMS will likely be quick to point out that they have established an ever-increasing litany of "quality" measures self-reported by the hospitals that show increasing compliance with these measures (8). However, the lack of improvement in patient outcomes (see below) suggests that completion of these has little meaningful effect.

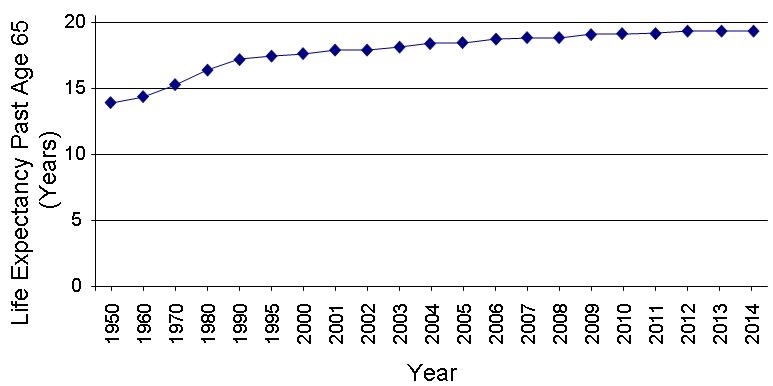

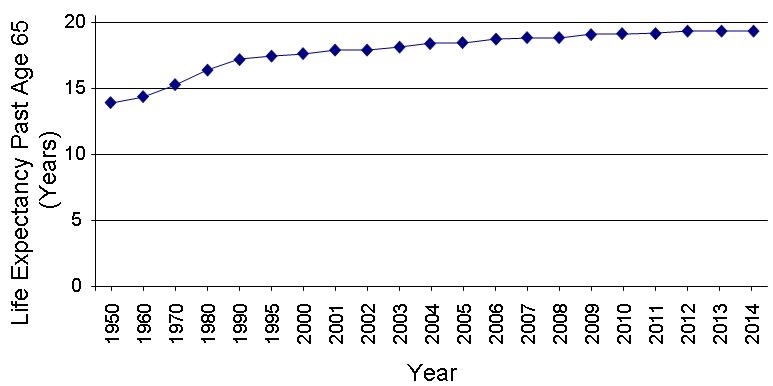

Life Expectancy

Although life expectancy for the Medicare age group is improving, the increase likely reflects a long-term improvement in life expectancy and may be slowing over the past few years (Figure 1) (9). Since 2005, life expectancy at birth in the U.S. has increased by only 1 year (10).

Figure 1. Life expectancy past age 65 by year.

The reason(s) for the declining improvement in life expectancy in the twenty-first century compared to the dramatic improvements in the twentieth are unclear but likely multifactorial. However, one possible contributing factor to a slowing improvement in mortality is a declining or flattening rate of improvement in healthcare.

Inpatient Mortality

Figueroa et al. (11) examined the association between HVBP and patient mortality in 2,430,618 patients admitted to US hospitals from 2008 through 2013. Main outcome measures were 30-day risk adjusted mortality for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia using a patient level linear spline analysis to examine the association between the introduction of the HVBP program and 30-day mortality. Non-incentivized, medical conditions were the comparators. The difference in the mortality trends between the two groups was small and non-significant (difference in difference in trends −0.03% point difference for each quarter, 95% confidence interval −0.08% to 0.13%-point difference, p=0.35). In no subgroups of hospitals was HVBP associated with better outcomes, including poor performers at baseline.

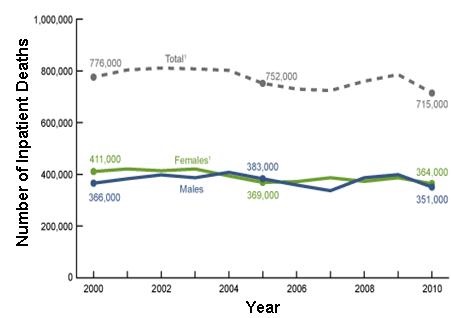

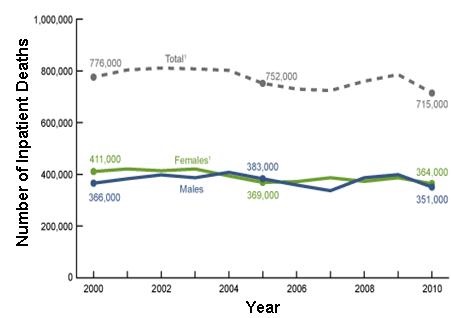

Consistent with Figueroa’s data, inpatient mortality trends declined only modestly from 2000 to 2010 (Figure 2) (12).

Figure 2. Number of inpatient deaths 2000-10.

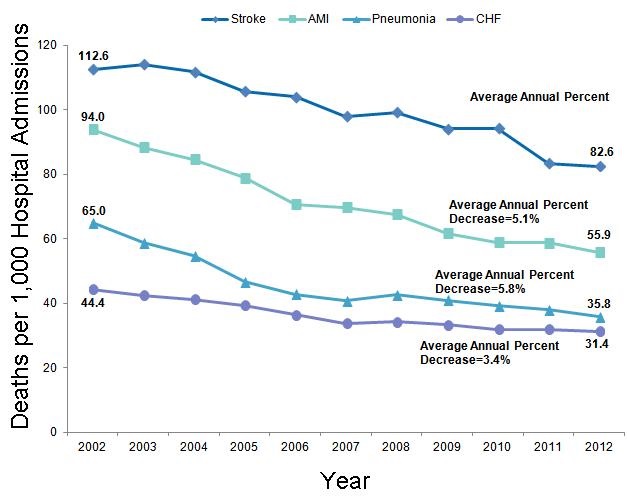

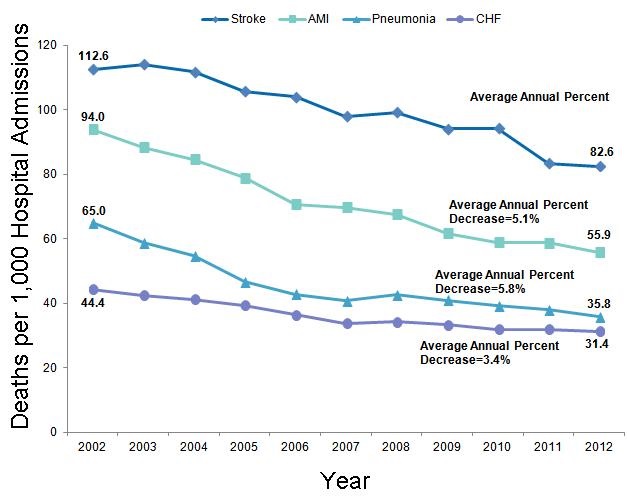

Although the decline was significant, the significance appears to be mostly explained by a greater that expected drop in 2010 and may not represent a real ongoing decrease. Consistent with the modest improvements seen in overall inpatient mortality, disease-specific mortality rates for stroke, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), pneumonia and congestive heart failure (CHF) all declined from 2002-12. However, the trend appears to have slowed since 2007 especially for CHF and pneumonia (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Inpatient mortality rates for stroke, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), pneumonia and congestive heart failure (CHF) 2002-12.

Consistent with the trend of slowing improvement, mortality rates for these four conditions declined at −0.13% for each quarter during from 2008 until Q2 2011 but only −0.03% from Q3 2011 until the end of 2013 (12).

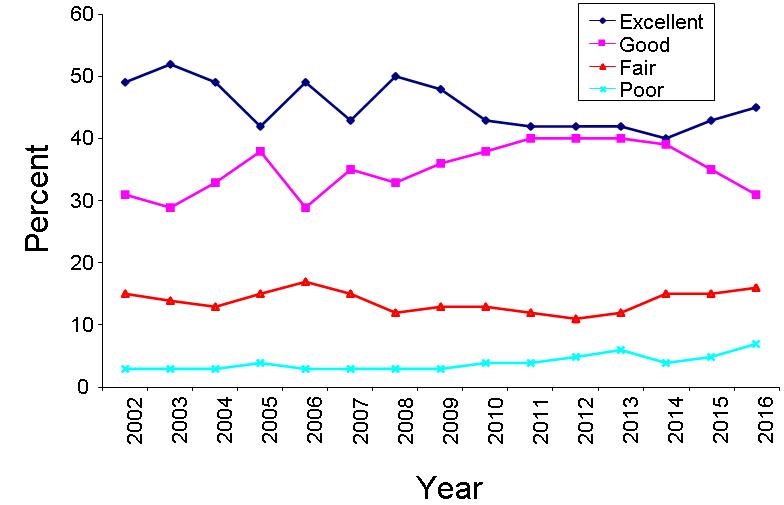

Patient Ratings of Healthcare

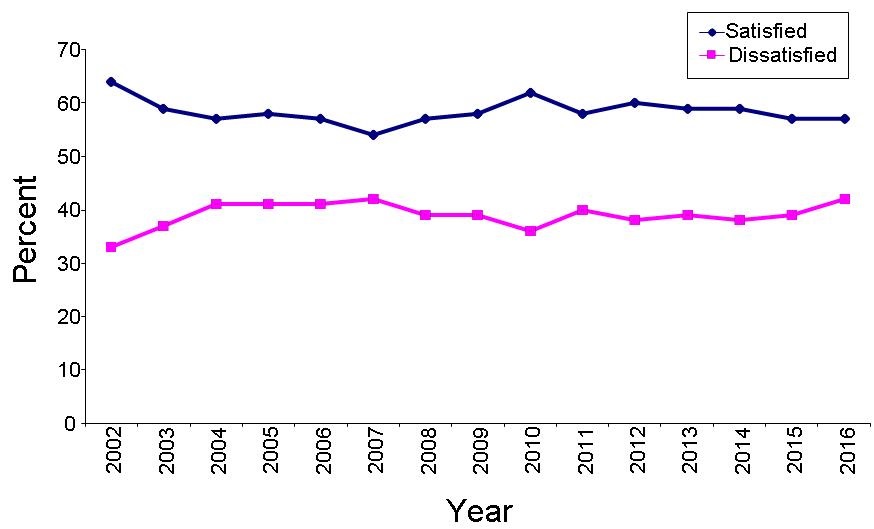

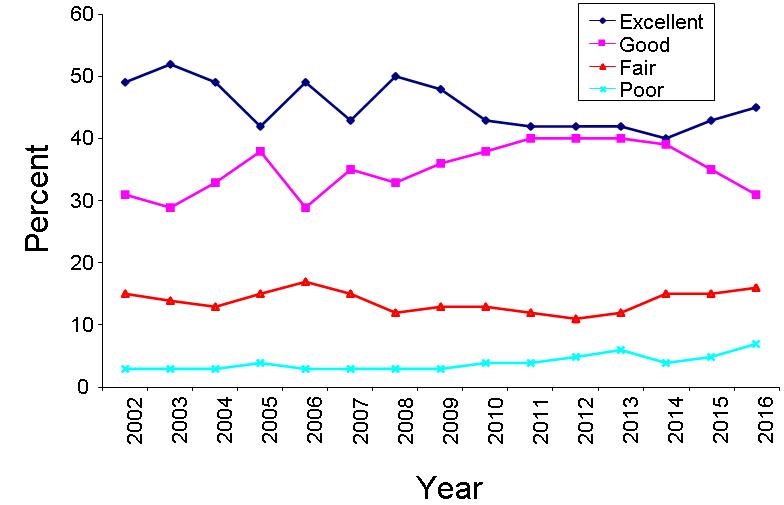

CMS has embraced the concept of patient satisfaction as a quality measure, even going so far as rating hospitals based on patient satisfaction (13). The Gallup company conducts an annual poll of Americans' ratings of their healthcare (14). In general, these have not improved and may have actually declined in the past 2 years (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Americans’ rating of their healthcare.

Cost

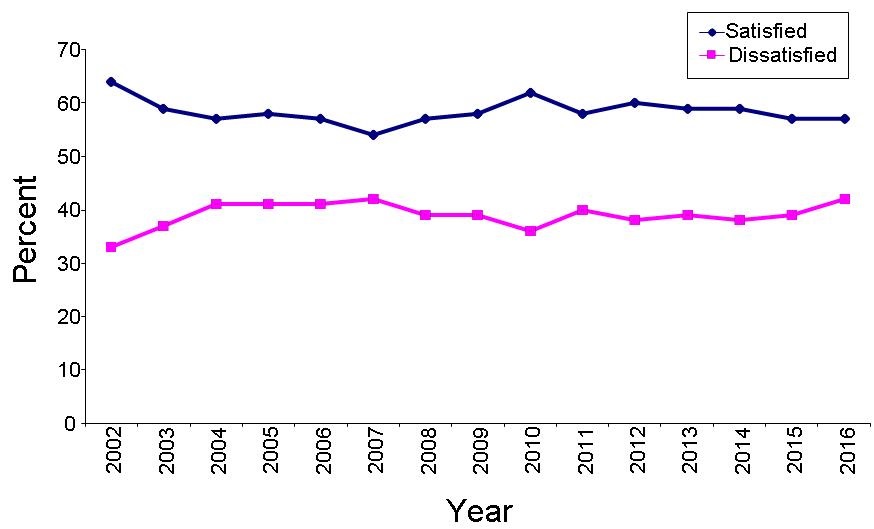

There is little doubt that healthcare costs have risen (15). The rising cost of healthcare has been cited as a major factor in Americans’ poor rating of their healthcare. The trend appears to be one of increasing dissatisfaction with the cost of healthcare (Figure 5) (16).

Figure 5. Americans’ satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the cost of healthcare.

Discussion

Americans have enjoyed remarkable improvements in life expectancy, mortality, and satisfaction with their healthcare over the past 100 years. However, the rate of these improvements appears to have slowed despite an ever-escalating cost. Starting with a much lower life expectancy in the US, primarily due to infections disease, the dramatic effect of antibiotics and vaccines on overall mortality in the twentieth century would be difficult to duplicate. The current primary causes of mortality in the US, heart disease and cancer, are perhaps more difficult to impact in the same way. However, declining healthcare quality may explain, at least in part, the slowing improvement in healthcare.

The evidence of lack, or only modest, improvement in patient outcomes is part of a disturbing trend in quality improvement programs by healthcare regulatory agencies. Under political pressure to “improve” healthcare, these agencies have imposed weak or non-evidence based guidelines for many common medical disorders. In the case of CMS, hospitals are required to show compliance improvement under the threat of financial penalties. Not surprisingly, hospitals show an improvement in compliance whether achieved or not (17). The regulatory agency then extrapolates this data from previous observational studies to show a decline in mortality, cost or other outcomes. However, actual measure of the outcomes is rarely performed. This difference is important because a reduction in a surrogate marker may not be associated with improved outcomes, or worse, the improvement may be fictitious. For example, many patients often die with a hospital-acquired infection. Certainly, hospital-acquired infections are associated with increased mortality. However, preventing the infections does not necessarily prevent death. For example, in patients with widely metastatic cancer, infection is a common cause of death. However, preventing or treating the infection, may do little other than delay the inevitable. A program to improve infections in these patients would likely have little effect on any meaningful patient outcomes.

There is also a trend of bundling weakly evidence-based, non-patient centered surrogate markers with legitimate performance measures (18). Under threat of financial penalties, hospitals are required to improve these surrogate markers, and not surprisingly their reports indicate they do. The organization mandating compliance with their outcomes reports that under their guidance hospitals have significantly improved healthcare saving both lives and money. However, if the outcome is meaningless or the hospital lies about their improvement, there is no overall quality improvement. There is little incentive for the parties to question the validity of the data. The organization that mandates the program would be politically embarrassed by an ineffective program and the hospital would be financially penalized for honest reporting.

Improvement begins with the establishment of measures that are truly evidence-based. Surrogate markers should only be used when improvement in that marker has been unequivocally shown to improve patient-centered outcomes. The validity of the data also needs to be independently confirmed. Those regulatory agency-demanded quality improvement programs that do not meet these criteria need to be regarded for what they are-political propaganda rather than real solutions.

The above data suggest that healthcare is improving little in what matters most, patient-centered outcomes. Those claims by regulatory agencies of improved healthcare should be regarded with skepticism unless corroborated by improvement in valid patient-centered outcomes.

References

- Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1966. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4):691-729. [PubMed]

- Affeldt JE. The new quality assurance standard of the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals. West J Med. 1980;132:166-70. [PubMed]

- Padrnos L, Bui T, Pattee JJ, et al. Analysis of overall level of evidence behind the Institute of Healthcare Improvement ventilator-associated pneumonia guidelines. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care 2011;3:40-8.

- Edwards JR, Peterson KD, Andrus ML, et al; NHSN Facilities. National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Report, data summary for 2006, issued June 2007. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(5):290-301. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudeck MA, Weiner LM, Allen-Bridson K, et al. National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) report, data summary for 2012, device-associated module. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(12):1148-66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metersky ML, Wang Y, Klompas M, Eckenrode S, Bakullari A, Eldridge N. Trend in ventilator-associated pneumonia rates between 2005 and 2013. JAMA. 2016 Dec 13;316(22):2427-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitman E. Fewer hospitals earn Medicare bonuses under value-based purchasing. Medscape. November 1, 2016. Available at: http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20161101/NEWS/161109986 (accessed 11/3/16).

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2015 national impact assessment of the centers for medicare & medicaid services (CMS). quality measures report. March 2, 2015. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/qualitymeasures/downloads/2015-national-impact-assessment-report.pdf (accessed 11/3/16).

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2015: With Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Hyattsville, MD. 2016. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus15.pdf#015 (accessed 11/3/16).

- Johnson NB, Hayes LD, Brown K, Hoo EC, Ethier KA. CDC National health report: leading causes of morbidity and mortality and associated behavioral risk and protective factors—United States, 2005–2013October 31, 2014/ 63(04);3-27. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6304a2.htm (accessed 11/3/16).

- Figueroa JF, Tsugawa Y, Zheng J, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Association between the Value-Based Purchasing pay for performance program and patient mortality in US hospitals: observational study. BMJ. 2016 May 9;353:i2214.

- Centers for Disease Control. Trends in inpatient hospital deaths: national hospital discharge survey, 2000–2010. March 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db118.htm (accessed 11/3/16).

- CMS. First release of the overall hospital quality star rating on hospital compare. July 27, 2016. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2016-Fact-sheets-items/2016-07-27.html (accessed 11/3/16)

- Newport F. Ratings of U.S. healthcare quality no better after ACA. November 19, 2015. Available at: http://www.gallup.com/poll/186740/americans-own-healthcare-ratings-little-changed-aca.aspx (accessed 11/3/16).

- Robbins RA. National health expenditures: the past, present, future and solutions. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2015;11(4):176-85.

- Newport F. Ratings of U.S. healthcare quality no better after ACA. November 19, 2015. Available at: http://www.gallup.com/poll/186740/americans-own-healthcare-ratings-little-changed-aca.aspx (accessed 11/3/16).

- Meddings JA, Reichert H, Rogers MA, Saint S, Stephansky J, McMahon LF. Effect of nonpayment for hospital-acquired, catheter-associated urinary tract infection: a statewide analysis. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:305-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CMS. Bundled payments for care improvement (BPCI) initiative: general information. November 28, 2016. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/ (accessed 12/30/16).

Cite as: Robbins RA. Is quality of healthcare improving in the US? Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2017;14(1):29-36. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc110-16 PDF

Thursday, February 9, 2017 at 8:00AM

Thursday, February 9, 2017 at 8:00AM  editor,

editor,  journal,

journal,  medical,

medical,  negative,

negative,  publication,

publication,  ratings,

ratings,  resubmission,

resubmission,  review,

review,  toolkit,

toolkit,  writer

writer