Pulmonary Embolism and Pulmonary Hypertension in the Setting of Negative Computed Tomography

Thursday, March 31, 2016 at 8:00AM

Thursday, March 31, 2016 at 8:00AM Peter V. Bui, MD

Sapna Bhatia, MD

Dona J. Upson, MD, MA

Department of Internal Medicine

Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine

The University of New Mexico and Raymond G. Murphy VA Medical Center

Albuquerque, NM

Abstract

Introduction: Chronic pulmonary hypertension (PH) can display acute elevations in pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) in the setting of hypoxemia, pulmonary embolism (PE), and possibly sepsis.

Case Description: A 68-year-old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, recent tobacco cessation, and recent 2-vessel coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) presented with one to two weeks of respiratory symptoms and syncope on the day of admission. He was found to have a urinary tract infection and Escherichia coli bacteremia. Transthoracic echocardiography found a systolic PAP of 100-105 mmHg, increased from a mean PAP of 32 mmHg before CABG. PE was not seen on computed tomography angiography (CTA). Ventilation-perfusion scan two days later found evidence of subsegmental PE. PAP prior to discharge was 30-35 mmHg plus right atrial pressure.

Conclusion: PAP can rise substantially in the acute or subacute setting, particularly when multiple disease processes are involved, and decrease to (near) baseline with proper therapy. Chronic PH may even be protective. In a complex clinical setting with multiple possible etiologies for elevated PAP, clinicians should have a high suspicion for PE despite a negative CTA.

Abbreviation List

ADHF acute decompensated heart failure

CABG coronary artery bypass grafting

COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

CTA computed tomography angiography

CXR conventional chest radiograph

EF ejection fraction

HCAP healthcare-associated pneumonia

HFpEF heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

INR international normalized ratio

LV left ventricle

PAP pulmonary arterial pressure

PCWP pulmonary capillary wedge pressure

PE pulmonary embolism

PH pulmonary hypertension

RA right atrium/atrial

RV right ventricle/ventricular

RHC right heart catheterization

SaO2 arterial oxygen saturation

TTE transthoracic echocardiography

UTI urinary tract infection

VTE venous thromboembolism

VQ ventilation-perfusion

Introduction

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is classified into five groups (1). In the United States, the incidence and prevalence of PH and each of its five groups are largely unclear. Group 2, due to left heart disease, has a prevalence as high as 83% by transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) (2). For group 3, due to chronic lung disease, in a study measuring pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) by right heart catheterization (RHC), the prevalence of PH among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was 36% (3). Changes in PAP in the setting of acute or subacute pulmonary embolism (PE) are unknown. We present a patient found to have transient severely elevated PAP in the setting of a negative computed tomography angiography (CTA) and positive ventilation-perfusion (VQ) scan with distractors including HFpEF, COPD, and sepsis.

Case Presentation

A 68-year-old man with severe COPD on four liters per minute of supplemental oxygen, a 50-pack-year smoking history with cessation two months before admission, HFpEF, 3-vessel coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction involving the left circumflex artery, recent 2-vessel coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs), chronic prostatitis, and prostatic calculi presented after a syncopal episode. One day prior to admission, he experienced fevers to 40°C and shaking chills. On the day of admission, the patient woke up struggling for breath and experienced syncope while getting out of bed. He had been having altered mental status and one week of productive cough with greenish sputum. He did not have any other respiratory, urinary, and constitutional symptoms. He presented to an outside hospital, where he was treated for presumed sepsis secondary to a UTI and started on an antibiotic. He was transferred to our facility and admitted for a UTI and possible healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP).

At presentation at our facility, vital signs included a temperature of 36.8°C, heart rate of 87 beats per minute, blood pressure of 124 mmHg / 69 mmHg, respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation of 96% on three-to-four liters per minute of supplemental oxygen. The physical examination was notable for expiratory wheezing and trace lower extremity edema. White blood cell was 13.5 K/mm3, neutrophilia of 80.4%, troponin I of 0.048 ng/mL, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide of 2800 pg/mL, and urinalysis suggestive of UTI. An arterial blood gas was deemed unnecessary for unchanged supplemental oxygen, normal mentation, and lack of respiratory distress. Electrocardiography showed normal sinus rhythm, nonspecific ST and T wave abnormalities, and previously identified signs of inferior-posterior infarction without evidence of acute right heart strain. He did not receive chemoprophylaxis for venous thromboembolism (VTE) because of possible surgical intervention.

Ten days before admission (Table 1), he made a long distance drive to see Cardiothoracic Surgery for post-CABG follow-up.

Table 1. Timeline of events surrounding the patient’s hospitalization. Computed tomography angiography (CTA). Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Conventional chest radiographs (CXR). Ejection fraction (EF). International normalized ratio (INR). Pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP). Pulmonary embolism (PE). Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE). Urinary tract infection (UTI). Ventilation-perfusion (VQ).

He had an increased oxygen requirement from three-to-four to four-to-five liters per minute, bilateral lower extremity edema, and supratherapeutic international normalized ratio (INR) of 4.4 on warfarin for postoperative atrial fibrillation, that had since resolved. TTE showed a normal sized left ventricle (LV), LV ejection fraction of 50-55%, inferolateral wall akinesis, basal inferior wall akinesis, mildly dilated right ventricle (RV), mildly reduced RV systolic function, mildly dilated right atrium (RA), PAP of 70-80 mmHg, and right atrial pressure of 10-15 mmHg. The patient refused hospitalization. Furosemide and metolazone were increased, and warfarin discontinued. His INR was 1.4 four days before admission.

Outpatient medications included amiodarone, simvastatin 10 mg, aspirin 81 mg, metoprolol 25 mg three times a day, and furosemide 80-100 mg daily. Six weeks prior to admission, RHC found RA pressure of 12 mmHg, RV pressure of 45/15 mmHg, PAP of 45/25 mmHg with a mean pressure of 32 mmHg, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) of 15 mmHg, cardiac output of 7.98 L/min, cardiac index of 3.55 L/min/m2, SaO2 97%, mixed venous saturation of 71%, pulmonary vascular resistance of 2.1 dynes-sec-cm-5, and system vascular resistance of 782 dynes-sec-cm-5.

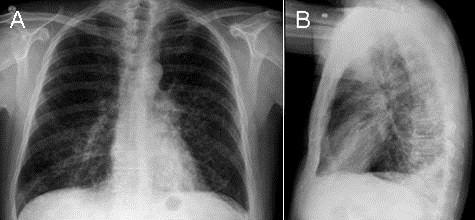

At presentation, his respiratory symptoms were attributed to pneumonia and not acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) or COPD. Initial antibiotics for HCAP and UTI coverage were cefepime and vancomycin. Conventional chest radiographs (CXRs) (Figure 1) on hospital day 0 and the CTA a few days later were not suggestive of pneumonia.

Figure 1. Conventional radiography of the chest showing no acute cardiopulmonary findings but enlarged pulmonary arteries.

An influenza viral panel was negative. Outside blood cultures grew Escherichia coli, while blood, urine, and sputum cultures from our facility were negative. CXRs over the following week were unchanged.

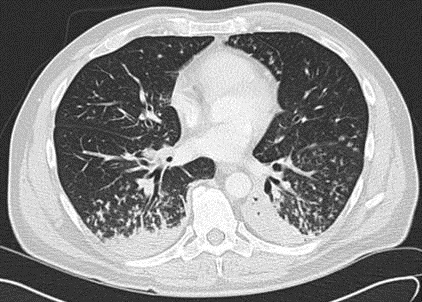

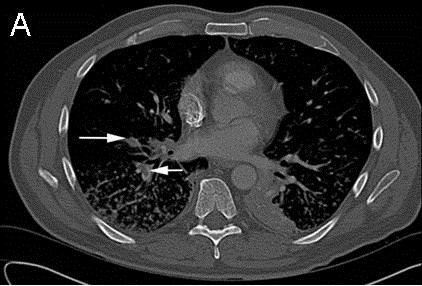

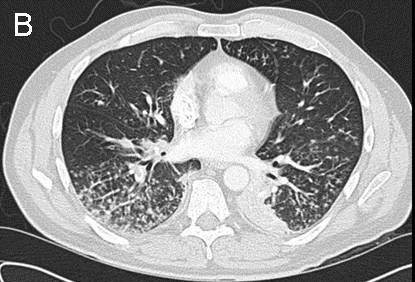

Because of the elevated PAP found prior to admission, Pulmonology was consulted for pulmonary hypertension. TTE on hospital day 3 found a normal RV size, mildly reduced RV systolic function, mildly dilated RA, systolic PAP of 100-105 mmHg, and RA pressure of <5 mmHg. His Wells score for PE was 3.0 to 4.5, suggesting moderate risk (4). The CTA did not identify a PE. In view of a high suspicion for PE, Pulmonology reviewed the CTA with a chest radiologist, who noted that the images were of suboptimal thickness. A VQ scan (Figure 2) was ordered on hospital day 5 and showed multiple bilateral VQ defects consistent with a high probability for PE.

Figure 2. Ventilation-perfusion scan on hospital day 5 showing multiple bilateral ventilation-perfusion defects. The study was consistent with a high probability for pulmonary embolism.

Ultrasound Doppler studies of the lower extremities on hospital day 6 were normal. Repeat TTE on hospital day 5 found a normal sized LV, LV EF of 45-50%, basal inferior wall akinesis, inferolateral wall akinesis, mildly dilated RV, mildly reduced RV systolic function, normal RA size, and PAP of 30-35 mmHg plus RA pressure. The patient was discharged on anticoagulation and antibiotics.

Discussion

We describe a patient who developed transiently elevated PAP in the setting of sepsis secondary to UTI and E. coli bacteremia, acute or subacute PE, HFpEF, and COPD. At baseline, he likely had PH from COPD and HFpEF out of proportion to PCWP. The increased PAP to 70-80 mmHg 1.5 weeks prior to admission was thought to be due to the hypervolemia observed by outpatient Cardiothoracic Surgery. Recent CABG, long-distance travel, and infection predisposed him to VTE. PE may have caused the dyspnea and syncope experienced on the day of admission. The negative CTA and systolic PAP of 100-105 mmHg on TTE on hospital day 3 may have reflected movement of PE downstream to the subsegmental or smaller arteries and thus inability to be seen on CTA, especially given the suboptimal thickness of the images. Volume status and vascular changes in the setting of recent hypervolemia, possibly due to HF or PH, and concurrent infection may have contributed to this elevated PAP. In light of the presentation of unexplained dyspnea and syncope, Wells score of 3.0 to 4.5, and elevated PAP, suspicion for PE was high. The high pretest probability of PE precipitated obtaining a VQ scan on hospital day 5. The scan supported the presence of bilateral PE, likely in the subsegmental or smaller arteries. PAP of 30-35 mmHg on subsequent TTE suggested resolution of PE.

CTA is the most common study to diagnose acute PE. A number of early studies found CTA to be at least as equivalent in sensitivity and specificity to VQ scan (5-10). Studies using data from the Prospective Investigation of Pulmonary Embolism Diagnosis (PIOPED) II found the sensitivity and specificity of CTA to be 83% and 96%, respectively, and of VQ scan to be 77.4%. and 97.7%, respectively (11, 12). However, CTA miss up to 20% to 36% of PE in subsegmental and smaller arteries (13-15). A meta-analysis of Wells criteria found sensitivity and specificity of 0.84 and 0.58, respectively, for a cutoff score of less than 2 and 0.60 and 0.80, respectively, for a cutoff score of 4 or less (16).

The degree to which HFpEF, COPD exacerbation, acute or subacute PE, and sepsis affect PAP has had limited investigation. In patients with ADHF, Aronson et al. (17) found PH in 42.6% and pulmonary arterial systolic pressures as high as 70 to 80 mmHg. Sibbald et al. (18) found that 57% of septic patients developed PH and had increases in mean PAP (27 ± 7 mmHg in septic patients found to have PH versus 15 ± 3 mmHg in septic patients found not to have PH, p < 0.01). In patients with chronic bronchitis who went into acute respiratory failure, Abraham et al. (19) found transient increases in mean PAP of approximately 15-20 mmHg (mean PAP 52.2 mmHg at admission and 36.5 mmHg prior to discharge).

The mechanism of PH can be mechanistically complex or intuitively simple. PH involves changes in nitric oxide, endothelin, thromboxane, and prostacyclin pathways, among other possible cellular and biological pathways of pulmonary endothelial dysfunction (20-25). Proinflammatory signals such as during infection affect these pathways (26). Other mechanisms include vascular congestion in HF, physical obstruction from PE, and vasoconstriction in hypoxemia leading to elevated PAP and subsequent PH (27-31). In our patient, there was likely a combination of several mechanisms contributing to his elevated PAP and PH.

Our patient may have been able to tolerate such an acute rise in pulmonary hypertension because of the effects of chronic pulmonary hypertension, although the pathophysiologic mechanisms have not been fully elucidated. Vonk-Noordegraaf et al. (32) described adaptive and maladaptive remodeling in pulmonary hypertension. In adaptive remodeling, the RV size is normal to moderately dilated; the RV mass/volume ratio is higher than normal, as seen in concentric remodeling; and the RVEF is normal to mildly decreased. For our patient, multiple TTE suggested adaptive remodeling, although our cardiologists did not comment on concentric remodeling.

We present the case of a patient with multiple comorbidities including HFpEF and COPD that likely caused the baseline PH seen on previous RHC and the subsequent development of severely increased PAP in the setting of sepsis and acute or subacute PE. His underlying chronic PH may have been protective given that he did not develop acute right HF from the sudden increase in PAP, and survived. The transient elevation in PAP in our patient reiterates that many disease processes can affect PAP, whether directly or indirectly, through simple or complex mechanisms. A CTA to evaluate possible PE should be verified to have the proper technique. A high suspicion for PE in the setting of acute PH despite a negative CTA warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Loren Ketai of the Department of Radiology of The University of New Mexico reviewed the images of the computed tomography angiography and ventilation-perfusion scans.

Cecilia Kieu assisted in the preparation of the figures for this manuscript.

References

-

Simonneau G, Gatzoulis MA, Adatia I, Celermajer D, Denton C, Ghofrani A, Gomez Sanchez MA, Krishna Kumar R, Landzberg M, Machado RF, Olschewski H, Robbins IM, Souza R. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Dec 24;62(25 Suppl):D34-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Lam CS, Roger VL, Rodeheffer RJ, Borlaug BA, Enders FT, Redfield MM. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a community-based study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Mar 31;53(13):1119-26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Andersen KH, Iversen M, Kjaergaard J, Mortensen J, Nielsen-Kudsk JE, Bendstrup E, Videbaek R, Carlsen J. Prevalence, predictors, and survival in pulmonary hypertension related to end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012 Apr;31(4):373-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, Ginsberg JS, Kearon C, Gent M, Turpie AG, Bormanis J, Weitz J, Chamberlain M, Bowie D, Barnes D, Hirsh J. Derivation of a simple clinical model to categorize patients probability of pulmonary embolism: increasing the models utility with the SimpliRED D-dimer. Thromb Haemost. 2000 Mar;83(3):416-20. [PubMed]

-

Blachere H, Latrabe V, Montaudon M, Valli N, Couffinhal T, Raherisson C, Leccia F, Laurent F. Pulmonary embolism revealed on helical CT angiography: comparison with ventilation-perfusion radionuclide lung scanning. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000 Apr;174(4):1041-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Chen SW, Mouratidis B. Comparison of lung scintigraphy and CT angiography in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Australas Radiol. 2002 Mar;46(1):47-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Macdonald WB, Patrikeos AP, Thompson RI, Adler BD, van der Schaaf AA. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: ventilation perfusion scintigraphy versus helical computed tomography pulmonary angiography. Australas Radiol. 2005 Feb;49(1):32-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Mayo JR, Remy-Jardin M, Müller NL, Remy J, Worsley DF, Hossein-Foucher C, Kwong JS, Brown MJ. Pulmonary embolism: prospective comparison of spiral CT with ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy. Radiology. 1997 Nov;205(2):447-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

McEwan L, Gandhi M, Andersen J, Manthey K. Can CT pulmonary angiography replace ventilation-perfusion scans as a first line investigation for pulmonary emboli? Australas Radiol. 1999 Aug;43(3):311-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Teigen CL, Maus TP, Sheedy PF 2nd, Stanson AW, Johnson CM, Breen JF, McKusick MA. Pulmonary embolism: diagnosis with contrast-enhanced electron-beam CT and comparison with pulmonary angiography. Radiology. 1995 Feb;194(2):313-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Stein PD, Fowler SE, Goodman LR, Gottschalk A, Hales CA, Hull RD, Leeper KV Jr, Popovich J Jr, Quinn DA, Sos TA, Sostman HD, Tapson VF, Wakefield TW, Weg JG, Woodard PK; PIOPED II Investigators. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2006 Jun 1;354(22):2317-27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Sostman HD, Stein PD, Gottschalk A, Matta F, Hull R, Goodman L. Acute pulmonary embolism: sensitivity and specificity of ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy in PIOPED II study. Radiology. 2008 Mar;246(3):941-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Goodman LR, Curtin JJ, Mewissen MW, Foley WD, Lipchik RJ, Crain MR, Sagar KB, Collier BD. Detection of pulmonary embolism in patients with unresolved clinical and scintigraphic diagnosis: helical CT versus angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995 Jun;164(6):1369-74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Oser RF, Zuckerman DA, Gutierrez FR, Brink JA. Anatomic distribution of pulmonary emboli at pulmonary angiography: implications for cross-sectional imaging. Radiology. 1996 Apr;199(1):31-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

van Rossum AB, Pattynama PM, Ton ER, Treurniet FE, Arndt JW, van Eck B, Kieft GJ. Pulmonary embolism: validation of spiral CT angiography in 149 patients. Radiology. 1996 Nov;201(2):467-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Lucassen W, Geersing GJ, Erkens PM, Reitsma JB, Moons KG, Büller H, van Weert HC. Clinical decision rules for excluding pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Oct 4;155(7):448-60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Aronson D, Darawsha W, Atamna A, Kaplan M, Makhoul BF, Mutlak D, Lessick J, Carasso S, Reisner S, Agmon Y, Dragu R, Azzam ZS. Pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular function, and clinical outcome in acute decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail. 2013 Oct;19(10):665-71. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Sibbald WJ, Paterson NA, Holliday RL, Anderson RA, Lobb TR, Duff JH. Pulmonary hypertension in sepsis: measurement by the pulmonary arterial diastolic-pulmonary wedge pressure gradient and the influence of passive and active factors. Chest. 1978 May;73(5):583-91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Abraham AS, Cole RB, Green ID, Hedworth-Whitty RB, Clarke SW, Bishop JM. Factors contributing to the reversible pulmonary hypertension of patients with acute respiratory failure studies by serial observations during recovery. Circ Res. 1969 Jan;24(1):51-60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Christman BW, McPherson CD, Newman JH, King GA, Bernard GR, Groves BM, Loyd JE. An imbalance between the excretion of thromboxane and prostacyclin metabolites in pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1992 Jul 9;327(2):70-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Cooper CJ, Jevnikar FW, Walsh T, Dickinson J, Mouhaffel A, Selwyn AP. The influence of basal nitric oxide activity on pulmonary vascular resistance in patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1998 Sep 1;82(5):609-14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Cooper CJ, Landzberg MJ, Anderson TJ, Charbonneau F, Creager MA, Ganz P, Selwyn AP. Role of nitric oxide in the local regulation of pulmonary vascular resistance in humans. Circulation. 1996 Jan 15;93(2):266-71. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Giaid A, Saleh D. Reduced expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the lungs of patients with pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1995 Jul 27;333(4):214-21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Giaid A, Yanagisawa M, Langleben D, Michel RP, Levy R, Shennib H, Kimura S, Masaki T, Duguid WP, Stewart DJ. Expression of endothelin-1 in the lungs of patients with pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1993 Jun 17;328(24):1732-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Moraes DL, Colucci WS, Givertz MM. Secondary pulmonary hypertension in chronic heart failure: the role of the endothelium in pathophysiology and management. Circulation. 2000 Oct 3;102(14):1718-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Toney BM, Fisher AJ, Albrecht M, Lockett AD, Presson RG, Petrache I, Lahm T. Selective endothelin-A receptor blockade attenuates endotoxin-induced pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vascular dysfunction. Pulm Circ. 2014 Jun;4(2):300-10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Barman SA. Potassium channels modulate hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol. 1998 Jul;275(1 Pt 1):L64-70. [PubMed]

-

Setaro JF, Cleman MW, Remetz MS.The right ventricle in disorders causing pulmonary venous hypertension. Cardiol Clin. 1992 Feb;10(1):165-83. [PubMed]

-

Gelband CH, Gelband H. Ca2+ release from intracellular stores is an initial step in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction of rat pulmonary artery resistance vessels. Circulation. 1997 Nov 18;96(10):3647-54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Post JM, Hume JR, Archer SL, Weir EK. Direct role for potassium channel inhibition in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol. 1992 Apr;262(4 Pt 1):C882-90. [PubMed]

-

Wang J, Juhaszova M, Rubin LJ, Yuan XJ. Hypoxia inhibits gene expression of voltage-gated K+ channel alpha subunits in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest. 1997 Nov 1;100(9):2347-53. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Haddad F, Chin KM, Forfia PR, Kawut SM, Lumens J, Naeije R, Newman J, Oudiz RJ, Provencher S, Torbicki A, Voelkel NF, Hassoun PM. Right heart adaptation to pulmonary arterial hypertension: physiology and pathobiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Dec 24;62(25 Suppl):D22-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Bui PV, Bhatia S, Upson DJ. Pulmonary embolism and pulmonary hypertension in the setting of negative computed tomography. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2016 Mar;12(3):116-25. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc016-16 PDF