January 2024 Medical Image of the Month: Polyangiitis Overlap Syndrome (POS) Mimicking Fungal Pneumonia

Tuesday, January 2, 2024 at 8:00AM

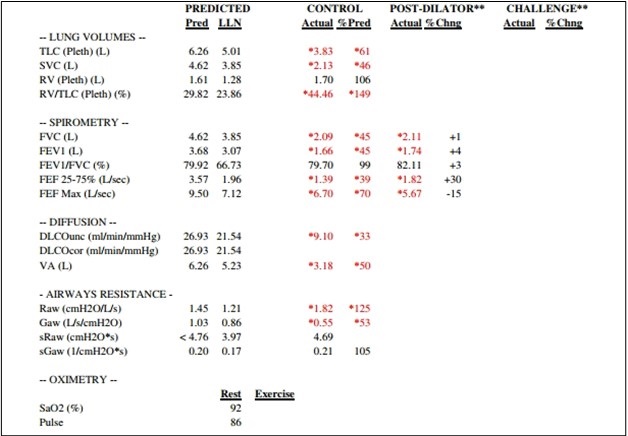

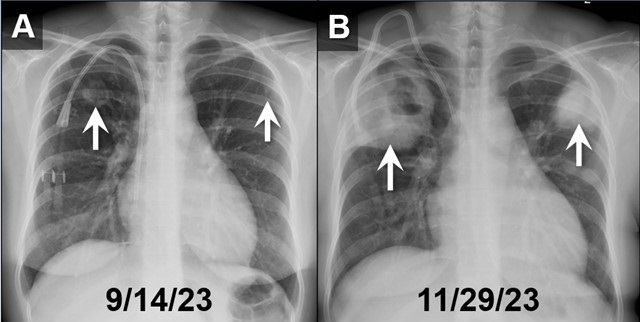

Tuesday, January 2, 2024 at 8:00AM  Figure 1. PA chest radiographs obtained on 9/14/23 (A) and approximately 2.5 months later (B) demonstrates rapidly growing cavitary masses in the upper lungs (arrows). The rapid interval growth is more suggestive of an inflammatory as opposed to malignant process. To view Figure 1 in a separate, enlarged window click here.

Figure 1. PA chest radiographs obtained on 9/14/23 (A) and approximately 2.5 months later (B) demonstrates rapidly growing cavitary masses in the upper lungs (arrows). The rapid interval growth is more suggestive of an inflammatory as opposed to malignant process. To view Figure 1 in a separate, enlarged window click here.

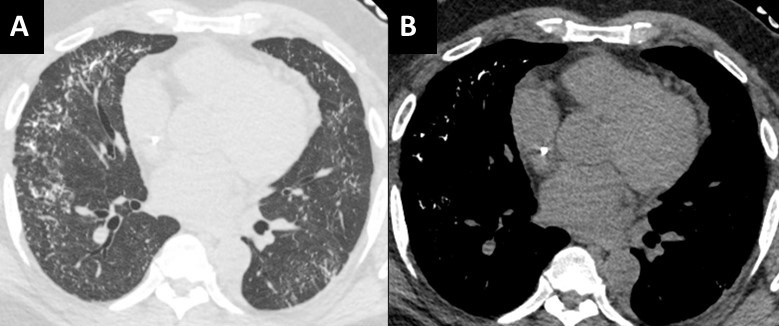

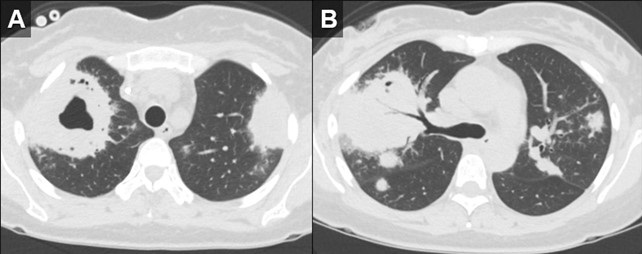

Figure 2. Axial reconstructions from an unenhanced chest CT (A,B) demonstrate multiple areas of mass-like consolidation with some areas of cavitation and some internal air bronchograms. As was surmised from the CXRs, the appearance suggests an infections/inflammatory etiology. To view Figure 2 in a separate, enlarged window click here.

Figure 2. Axial reconstructions from an unenhanced chest CT (A,B) demonstrate multiple areas of mass-like consolidation with some areas of cavitation and some internal air bronchograms. As was surmised from the CXRs, the appearance suggests an infections/inflammatory etiology. To view Figure 2 in a separate, enlarged window click here.

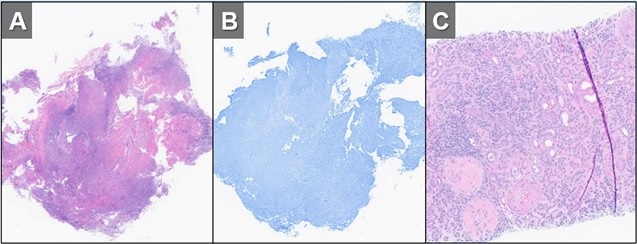

Figure 3. H&E (A) and GMS (B) stains of a specimen from biopsy of right upper lobe lesion. There is an organizing inflammatory process with extensive necrosis and no evidence of infectious organism. H&E staining of a renal biopsy (C) demonstrates chronic and active necrotizing and crescentic glomerulosclerosis with diffuse interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy. Taken in conjunction with the history and lack of any other findings to suggest infection, histopathological findings were deemed to be consistent with active granulomatosis with polyangiitis. To view Figure 3 in a separate, enlarged window click here.

Figure 3. H&E (A) and GMS (B) stains of a specimen from biopsy of right upper lobe lesion. There is an organizing inflammatory process with extensive necrosis and no evidence of infectious organism. H&E staining of a renal biopsy (C) demonstrates chronic and active necrotizing and crescentic glomerulosclerosis with diffuse interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy. Taken in conjunction with the history and lack of any other findings to suggest infection, histopathological findings were deemed to be consistent with active granulomatosis with polyangiitis. To view Figure 3 in a separate, enlarged window click here.

A 32-year-old woman with a history including hypertension, end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis, asthma, nonischemic cardiomyopathy, and migraines, was directly transferred to our hospital in November 2023 for the evaluation of hemoptysis. The patient reported a two-week history of a nonproductive cough, runny nose, muscle aches, subjective fevers, chills, fatigue, nausea, and decreased appetite. Within the past 2 days the patient had also developed hemoptysis, with 5-6 episodes per day.

Initial investigations, including chest X-ray and CT chest, revealed large biapical pulmonary consolidations with cavitation. Multiple nodular densities were observed throughout both lungs (Figures 1 and 2). The patient denied any recent sick contacts, travel history, and prior tuberculosis infection. She did, however, disclose a period of incarceration from 2011 to 2019.

Upon arrival at our hospital, the patient recounted a relatively normal state of health until January 2023 when she underwent a two-month hospitalization, culminating in the diagnosis of end-stage renal disease by biopsy at an outside facility. She attributed this to anautoimmune disease, for which she did not receive immunosuppressive therapy at the time. Subsequent hospitalization in September 2023 for rhinovirus pneumonia led to the diagnosis of heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction of 15-20%, determined to be of nonischemic origin.

In our ED vital signs revealed a heart rate of 110, blood pressure of 180/90 mmHg, normal respiratory rate, and no hypoxia on room air. Laboratory results were significant for leukocytosis 18.7x109/L with high eosinophils count of 2.32x109/L, elevated potassium 5.7 mmol/L, BUN 51 mg/dL, and creatinine 9.5 mg/dL. Chest X-ray depicted bilateral upper lung consolidations, notably worsened on the right with central cavitation (Figure 1B). Additional nodularity was observed in the left mid-lung, which was new in comparison to a prior chest x-ray done in September 2023 (Figure 1A).

Following her admission, an extensive infectious workup, including TB QuantiFERON testing, lumbar puncture, bronchoscopy with BAL, and blood cultures, was conducted. The results were unremarkable. Transbronchial biopsies from the right upper lobe cavity revealed an organizing inflammatory process with extensive necrosis, negative for neoplasm and infectious staining including GMS & acid-fast bacilli (Figure 3A,3B). An autoimmune panel revealed elevated ESR, CRP, PR3 antibody, and positive c-ANCA, leading to a diagnosis of Polyangiitis overlap syndrome. Treatment commenced with IV methylprednisone, transitioning to oral prednisone (60 mg daily) with a gradual taper over the next eight weeks. Inpatient administration of rituximab was initiated, with plans for three more infusions as part of her induction therapy.

According to the data from the French Vasculitis Study Group Registry (1), among the 795 patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), 354 individuals (44.5%) exhibited elevated blood eosinophil counts. Notably, hypereosinophilia, primarily of mild-to-moderate severity (ranging from 500 to 1500/mm3), was identified in approximately one-quarter of GPA patients at the time of diagnosis. In contrast, severe eosinophilia (>1500/mm3) was observed in only 28 patients (8%). Furthermore, this subset with severe eosinophilia was noted to have worse renal function at the time of presentation. Whereas in a retrospective European multicentre cohort published by Papo et al. (2), ANCA status was accessible for 734 EGPA patients with only 16 patients (2.2%) having PR3-ANCA. Notably, at baseline, PR3-ANCA positive patients, in comparison to those with MPO-ANCA and ANCA-negative individuals, exhibited a lower prevalence of active asthma and peripheral neuropathy. Conversely, they manifested a higher incidence of cutaneous manifestations and pulmonary nodules. Adding to the complexity, EGPA, characterized by peripheral blood eosinophilia, asthma, and chronic rhinosinusitis, contrasts with GPA, which manifests pulmonary nodules without eosinophilic infiltration and usually a more severe renal disease.

Polyangiitis overlap syndrome (POS), previously published by Leavitt and Fauci (3), was defined as systemic vasculitis that does not fit precisely into a single category of classical vasculitis or overlaps more than one subtype of vasculitis. Several polyangiitis overlap syndromes have been identified since 1986; however, less than 20 case reports of an overlap syndrome involving both GPA and EGPA have been published so far. As per the literature review performed by Bruno et al. (4), most of the reported POS cases had lung involvement with over half developed alveolar hemorrhage. They noted genetic and clinical heterogeneity in the pathogenesis of polyangiitis overlap syndrome suggesting distinct clinical phenotypes and outcomes to therapy. Notably, treatment strategies in polyangiitis overlap syndrome are usually tailored to the severity of the disease rather than the ANCA phenotype, leading to favorable outcomes in most cases.

John Fanous MD1, Clint Jokerst MD2, Rodrigo Cartin-Ceba MD1

Division of Pulmonology1and Department of Radiology2

Mayo Clinic Arizona, Scottsdale, AZ USA

References

- Iudici M, Puéchal X, Pagnoux C, et al.; French Vasculitis Study Group. Significance of eosinophilia in granulomatosis with polyangiitis: data from the French Vasculitis Study Group Registry. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022 Mar 2;61(3):1211-1216. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papo M, Sinico RA, Teixeira V, et al.; French Vasculitis Study Group and the EGPA European Study Group. Significance of PR3-ANCA positivity in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss). Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Sep 1;60(9):4355-4360. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leavitt RY, Fauci AS. Pulmonary vasculitis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986 Jul;134(1):149-66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno L, Mandarano M, Bellezza G, Sidoni A, Gerli R, Bartoloni E, Perricone C. Polyangiitis overlap syndrome: a rare clinical entity. Rheumatol Int. 2023 Mar;43(3):537-543. [CrossRef] [PubMed]