Breaking the Guidelines for Better Care

Saturday, June 10, 2017 at 8:00AM

Saturday, June 10, 2017 at 8:00AM Two events happened this past week that inspired this editorial. First, on Wednesday morning I read the editorial titled “Breaking the Rules for Better Care” by Don Berwick et al. in JAMA (1). Berwick reports a survey of about 40 hospitals done by The Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI). The survey asked the question “If you could break or change any rule in service of a better care experience for patients or staff, what would it be?”. The answers were not surprising. Most centered on annoying hospital rules such as visiting hours, not waking patients, correct HIPPA interpretation, and eliminating the 3-day rule. Although these are correct, in the whole they have minimal effect on healthcare. Other suggestions more likely to improve patient care included improving access, reducing wait times and earlier patient mobility. From the suggestions, it seems likely that most were from administrators. In the editorial Berwick decried, “Habits embedded in organizational behaviors, based on misinterpretations and with little to no actual foundation in legal, regulatory, or administrative requirements”. He goes on to say, “Health care leaders may be well advised to ask their clinicians, staffs, and patients which habits and rules appear to be harming care without commensurate benefits and, with prudence and circumspection, to change them.” As a clinician, I thoroughly agree with both of Berwick’s points.

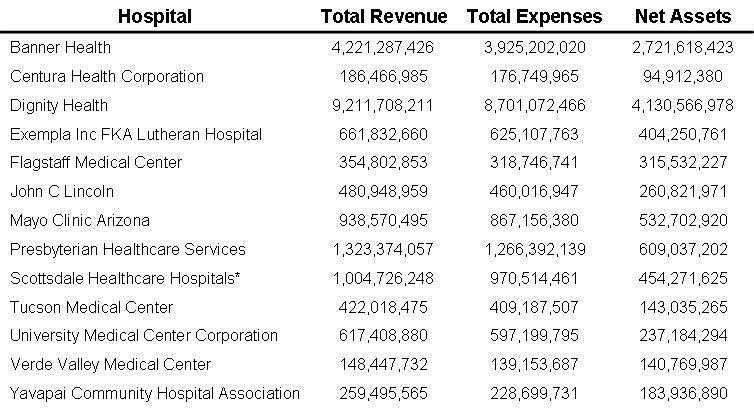

Later that afternoon, I listened to a lecture by Clement Singarajah on sepsis guidelines. He reviewed the severe sepsis bundles promoted by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign and IHI, the latter being Berwick’s organization who wrote the editorial noted above (Table 1) (2,3).

Table 1. Severe Sepsis Bundles.

The Severe Sepsis 3-Hour Resuscitation Bundle contains the following elements, to be completed within 3 hours of the time of presentation with severe sepsis:

- Measure Lactate Level

- Obtain Blood Cultures Prior to Administration of Antibiotics

- Administer Broad Spectrum Antibiotics

- Administer 30 mL/kg Crystalloid for Hypotension or Lactate ≥4 mmol/L

The 6-Hour Septic Shock Bundle contains the following elements, to be completed within 6 hours of the time of presentation with severe sepsis:

- Apply Vasopressors (for Hypotension That Does Not Respond to Initial Fluid Resuscitation to Maintain a Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) ≥65 mm Hg)

- In the Event of Persistent Arterial Hypotension Despite Volume Resuscitation (Septic Shock) or Initial Lactate ≥4 mmol/L (36 mg/dL):

- Measure Central Venous Pressure (CVP)

- Measure Central Venous Oxygen Saturation (ScvO2)

- Remeasure Lactate If Initial Lactate Was Elevated

We carefully reviewed each of the metrics, and concluded most were non-evidence based, outdated, or contradicted by more recent and better trials. The only exception was early antibiotic administration. Most of us reaffirmed our belief in the germ theory and felt that early administration of the correct antibiotics was probably mostly evidence-based and reasonable (4).

Is it possible that most of the metrics in the bundle are merely a waste of time as we concluded or could some be harmful? First, a recent meta-analysis examined a conservative fluid strategy in sepsis compared with a liberal strategy (the goal-directed therapy as advocated by the sepsis bundles) (5). Although there was no change in mortality, a conservative strategy resulted in increased ventilator-free days and reduced length of ICU stay. The meta-analysis concluded that the studies were underpowered to show a mortality benefit. Second, most of us had experienced delays in initiating antibiotics, the only guideline that makes a difference, while waiting for blood cultures to be drawn. None of us knew data that drawing blood cultures makes a difference in patient outcomes.

Berwick recommended asking clinicians which rules may be harming care. Rather than chiding others to do something, a good place to start might be IHI’s sepsis guidelines. The issue of continued support for non-evidence based or outdated guidelines points out the rigid dichotomy between self-delusional beliefs and science. Many (some would say most) guidelines are based on opinions and not science (6). Healthcare would be better if groups such as the Surviving Sepsis Campaign, IHI and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services would follow their own advice and not burden healthcare providers with non-evidence based guidelines. Instead, they should only issue guidelines after carefully conducted, randomized, controlled trials establish a guideline rather than mandating the self-delusional beliefs of a few.

Richard A. Robbins, MD

Editor, SWJPCC

References

- Berwick DM, Loehrer S, Gunther-Murphy C. Breaking the rules for better care. JAMA. 2017 Jun 6;317(21):2161-2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surviving Sepsis Campaign. Updated bundles in response to new evidence. Available at: http://www.survivingsepsis.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/SSC_Bundle.pdf (accessed 6/9/17).

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Severe sepsis bundles. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/SevereSepsisBundles.aspx (accessed 6/9/17).

- Seymour CW, Gesten F, Prescott HC, et al. Time to treatment and mortality during mandated emergency care for sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2017 Jun 8;376(23):2235-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silversides JA, Major E, Ferguson AJ, et al. Conservative fluid management or deresuscitation for patients with sepsis or acute respiratory distress syndrome following the resuscitation phase of critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2017 Feb;43(2):155-170. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee DH, Vielemeyer O. Analysis of overall level of evidence behind Infectious Diseases Society of America practice guidelines. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:18-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Robbins RA. Breaking the guidelines for better care. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2017;14(6):285-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc072-17 PDF