A Call for Change in Healthcare Governance

Saturday, June 29, 2024 at 8:00AM

Saturday, June 29, 2024 at 8:00AM Over the past 30-40 years many healthcare organizations have gradually shifted from a charitable, not-for-profit organization to a not-for-profit in name only business. Accompanying this shift, has been a shift in hospital governance away from a benevolent organization directed by charitable organizations such as religious organizations to businessman focused on revenue and profits. Of course, this does not mean that not-for-profit organizations are for loss. Small or modest profits are necessary to continue to operate.

Accompanying this change in organizational goals from a charitable to a more business focus, has been changes in the hospital board of directors or trustees (1). The mission of a publicly traded corporation is to return economic value to their shareholders and is the primary fiduciary focus of that board. On the other hand, the mission of a not-for-profit, 501c, charitable healthcare system is to provide health services improving the well-being of the community.

The board of directors or trustees of a not-for-profit organization theoretically must be primarily focused on the fulfillment of the charitable mission, not on generating profit for its own sake. Not-for-profit boards tend to be larger. In the 1980s the average size of a not-for-profit hospital board was well over 25, but is declining. By 2023 the average size was around 13 (1). At least 51% of the members of a not-for-profit charitable board must meet the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) definition of independence. This means that these board members must be independent of direct economic relationships with the organization and not have direct family members who work for the organization. This is one way that the IRS tries to ensure that the board is loyal to the charitable mission of the organization.

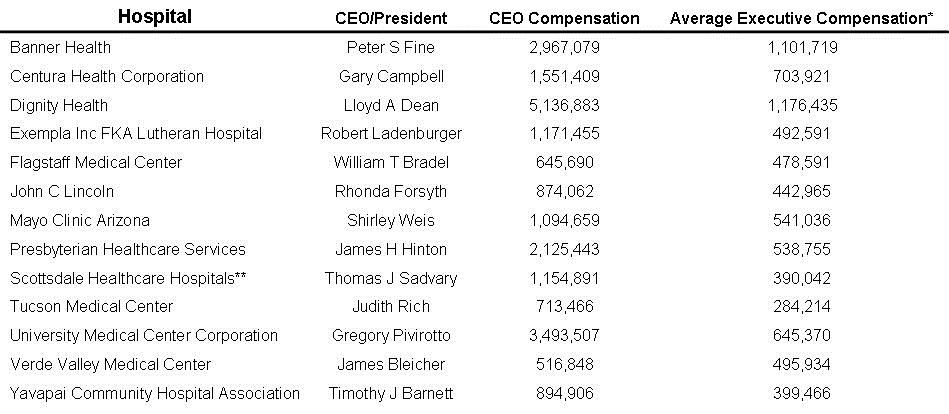

In the 1980’s new board members were often elected by the board and usually received no or minimal compensation (2). However, today board members are often “nominated” by the administration of the hospital and often receive compensation which can be substantial (2). For example, the 14 board members of Banner Health receive in excess of $95,000/year (3). In addition, hospital CEOs were usually ex officio non-voting board members. Again, using Banner Health as an example, the CEO is a full board member (4). Board composition has also changed. In the past there was often ample physicians and nurses providing medical guidance to the board. Today their numbers have dwindled. Banner has only 2 physicians on its 14-member board (an internist/emergency room and a family physician). Nursing is not represented.

The role of the chief of staff (COS) has also changed. In the past COSs were usually members of the medical faculty who served one or two years on a part-time basis. They were compensated but that was largely to offset their loss of income as a physician. Now COSs are often full-time serving at the pleasure of the hospital CEO and/or board. They are no longer the doctors’ representative to the hospital administration but rather the hospital administration’s representative to the doctors (5). The concept that the COS can work in a “kumbaya” relationship with hospital administrators is a naive remanent from a bygone era. Although a good working relationship may exist in some healthcare organizations, increasingly the relationship is adversarial.

Physician practice has also changed. In the past physicians were often self-employed independents who practiced within the confines of the hospital or clinic. Now 77% of physicians are employed, a dramatic increase from 26% only 10 years ago (6). The reason most often cited has been declining reimbursement (7). Although cost containment is often cited as a reason for the decline, Medicare physician pay has plummeted by 26% when adjusted for inflation over the past 20 years while hospital reimbursement has surged by 70% (7). The decline in reimbursement has prompted many doctors to abandon independent practice for hospital or corporate employment (7). Some have equated increasing physician employment for decreasing access and quality of care (7).

It seems unlikely that without a change in governance any meaningful change in the businessmen’s stranglehold of medicine with its poor care, high prices and administrative overcompensation will be forthcoming. One simple improvement is election of the COS by an independent medical staff rather than appointment by a hospital director or board.

A second, also simple change is that independent doctors, nurses and technicians need to have their representation increased on the board of directors of the hospital or healthcare organization. They should be elected by the hospital staff and not appointed by the CEO. Rather than just requiring 51% of board members be independent, at least 51% of boards should have doctors, nurses or technicians who practice at the hospital or healthcare organization but are independent. This ensures adequate medical expertise including local knowledge about the operation of the organization.

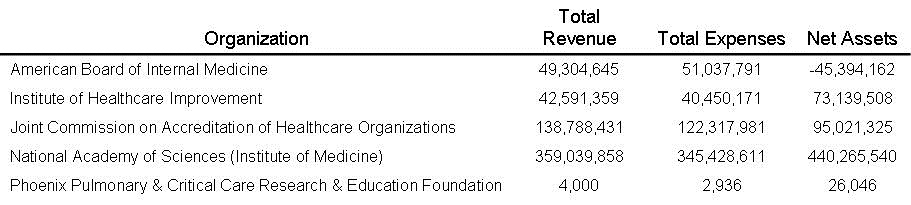

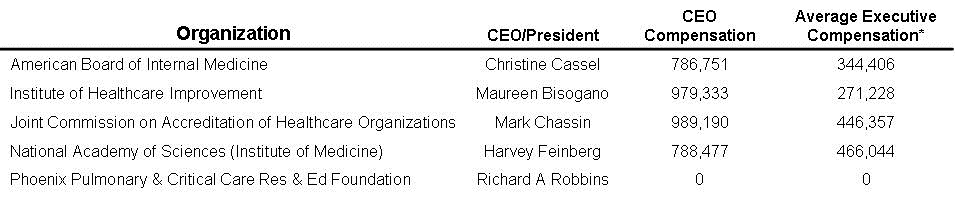

Changes described above to the COS and board of directors should be required by the Joint Commission, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, the state department of health and possibly the IRS. These changes could go a long way to resolving the intrusion in medicine by businessmen interested more in their own gain and not the charitable healthcare mission of a 501c hospital or healthcare organization.

References

- Wagner SE. A Taxonomy of Health Care Boards. Trustee Insights. American Hospital Association. September, 2023. Available at: https://trustees.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2023/09/TI_0923_orlikoff_interview_3.pdf (accessed 6/14/2024).

- Blodgett MS, Melconian LJ, Peterson JH. Evolving Corporate Governance Standards for Healthcare Nonprofits: Is Board of Director Compensation a Breach of Fiduciary Duty. Brooklyn Journal of Corporate Financial & Commercial Law. 2013;7(2): 444-474. Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1046&context=bjcfcl (accessed 6/14/2024).

- ProPublica. Nonprofit Explorer. December 2022 Tax Filing. Available at: https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/organizations/450233470 (accessed 6/14/24).

- Board of Directors. Banner Health. Available at: https://www.bannerhealth.com/about/leadership/board-of-directors (accessed 6/14/24).

- Robbins RA. The Potential Dangers of Quality Assurance, Physician Credentialing and Solutions for Their Improvement. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care Sleep. 2022;25(4):52-58. [CrossRef]

- Physicians Advocacy Institute. Updated Report: Hospital and Corporate Acquisition of Physician Practices and Physician Employment 2019-2023. April 2024. Available at: https://www.physiciansadvocacyinstitute.org/Portals/0/assets/docs/PAI-Research/PAI-Avalere%20Physician%20Employment%20Trends%20Study%202019-2023%20Final.pdf?ver=uGHF46u1GSeZgYXMKFyYvw%3d%3d (accessed 6/16/24).

- G Grossi. Dr David Eagle: CMS Reimbursement Cuts Encourage Trend of Independent Physician Exodus. American Journal of Managed Care. Feb 12, 2024. Available at: https://www.ajmc.com/view/dr-david-eagle-cms-reimbursement-cuts-encourage-trend-of-independent-physician-exodus (accessed 6/16/24).

501c,

501c,  CMS,

CMS,  businees,

businees,  charity,

charity,  chief of staff,

chief of staff,  compensation,

compensation,  for profit,

for profit,  governance,

governance,  hospital board,

hospital board,  not for profit

not for profit