Medicare for All-Good Idea or Political Death?

Friday, July 26, 2019 at 1:06PM

Friday, July 26, 2019 at 1:06PM Several Democratic presidential candidates have pushed the idea of “Medicare for All” and a “Medicare for All” bill has been introduced into the US house with over 100 sponsors. A recent Medpage Today editorial by Milton Packer asks whether this will benefit patients or physicians (1). Below are our views on “Medicare for All” with the caveat that we do not speak for the American Thoracic Society nor any of its chapters.

It has been repeatedly pointed out that medical care in the US costs too much. US health care spending grew 3.9 percent in 2017, reaching $3.5 trillion or $10,739 per person, and 17.9% of the gross domestic product (GDP) (2). This is more than any industrialized country. Furthermore, our expenditures continue to rise faster than most other comparable countries such as Japan, Germany, England, Australia and Canada (2).

Despite the high costs, the US does not provide access to healthcare for all of its citizens. In 2017, 8.8 percent of people, or 28.5 million, did not have health insurance at any point during the year (3). In contrast, other comparable industrialized countries provide at least some care for everyone.

Furthermore, our outcomes are worse. Infant mortality is higher than any similar country (4). US life expectancy is shorter at 78.6 years compared to just about any comparable industrialized company with Japan leading the way at 84.1 years. All the Western European countries (such as Germany, France, England, etc.), as well as Australia and Canada have a longer life expectancy than the US (range 81.8-83.7 years).

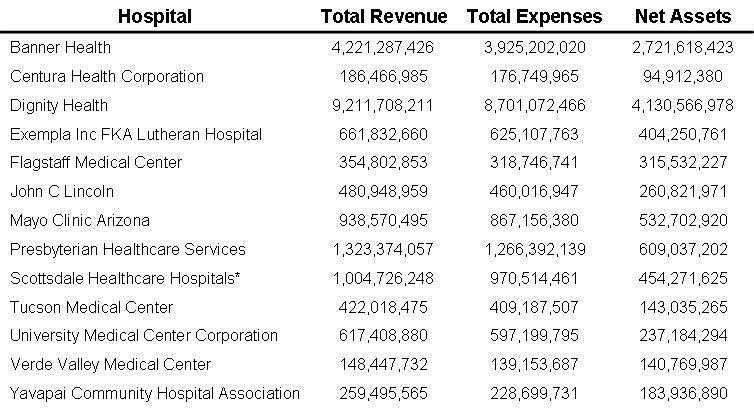

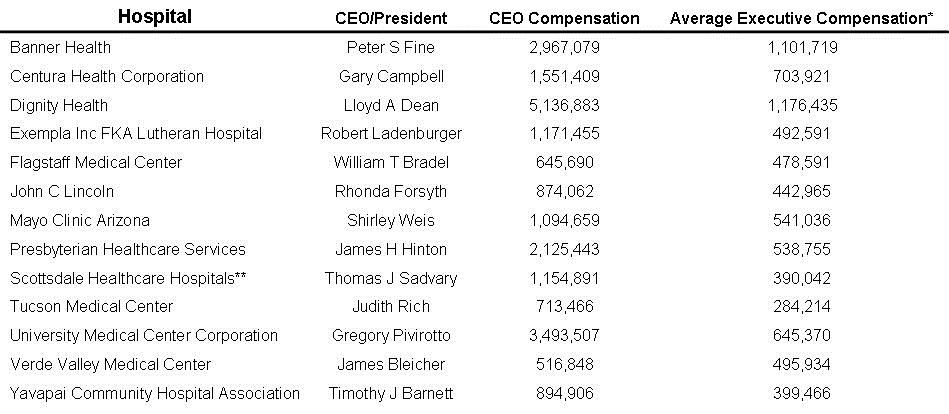

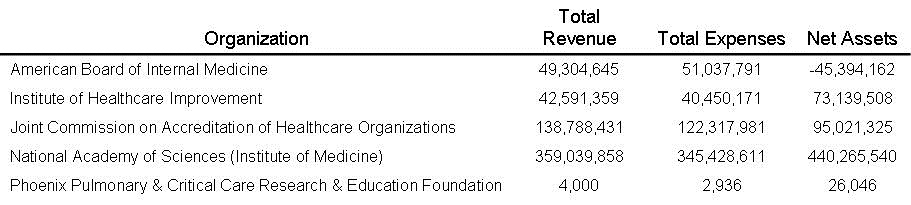

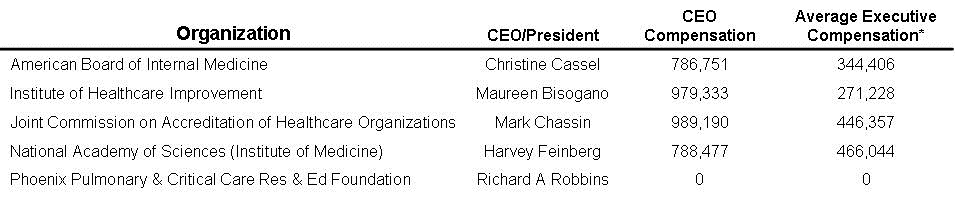

Our high infant mortality and lagging life expectancy was not always so. In 1980, the US had similar infant mortality and life expectancy when compared to other industrialized countries. Why did we lose ground over the last 40 years? Beginning in about 1980, there have been increasing business pressures on our healthcare system. In his editorial, Packer called our system "financialized" to an extreme (1). Hospitals, pharmaceutical and device companies, insurance companies, pharmacies and sadly, even some physicians often price their products and services not according to what is fair or good for patients but to maximize profit. By incentivizing procedures that often do not benefit patients but benefit the businessmen’s’ pockets, these practices likely account for the high costs and for our worsening outcomes.

Packer points out that in the US, intermediaries (insurers and pharmacy benefit managers) exert considerable control of payment while unnecessarily adding to the administrative costs of healthcare. Congress has been pressured to forbid Medicare from negotiating prices with pharmaceutical companies benefitting only the drug manufacturers and those that benefit from the high drug prices. Consequently, administrative costs are four times higher and pharmaceuticals three times greater in the U.S. than in other countries.

If “Medicare for All” could reduce healthcare costs and improve outcomes, it might seem like a good idea. It has the potential for reducing administrative costs and assuming the power to negotiate drug prices was restored, pharmaceutical costs. However, it will be opposed by those who financially benefit from the present system including administrators, hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, pharmacy benefit managers, insurance companies, etc. Furthermore, there is a libertarian segment of the population that opposes any Government interference in healthcare, even those that would strengthen the free market principles that so many libertarians tout. There are already TV adds opposing “Medicare for All.” It seems likely that any “Medicare for All” or any similar plan will meet with considerable political opposition.

One solution might be to have both Government and non-Government plans. Assuming transparency in both services covered and costs, it leaves the choice in healthcare plans where it belongs-with those paying for the care. It also makes it much harder for those with financial or political interests to convincingly argue against a Government plan (although we are sure they will try). It will force insurance companies to reduce their prices and/or offer more coverage, which is not a bad thing for patients and ultimately, the healthcare system as a whole. However, it does impose a risk, i.e., that profit-driven insurance companies and those who benefit from the current infrastructure will be replaced by bureaucrats who are primarily concerned with administrative procedure rather than patient care. Present day examples include the VA, Medicare and Medicaid systems. Close public and medical oversight of such a system would be needed.

Ideally, a healthcare system should ensure that citizens can access at least a basic level of health services without incurring financial hardship and with the goal of improving health outcomes. Such a system, would provide a middle path between the extremes of paying for nothing and paying for everything such as unwarranted chemotherapy, stem cell therapy, or unnecessary diagnostic procedures. Determining what services are covered, and how much of the cost is covered are not easy questions to answer, but promises to deliver better health for less money than our current system. Physicians, by dint of their training, and responsibility to uphold their profession and protect their patients, understand that healthcare is not a mere commodity. If we are to protect what little autonomy we have left, we need to be a part of the discussion which should not be driven solely by those in the insurance, the hospital and the pharmaceutical industries.

Richard A. Robbins, MD1

Angela C. Wang, MD2

1Phoenix Pulmonary and Critical Care Research and Education Foundation, Gilbert, AZ USA

2Scripps Clinic Torrey Pines, La Jolla, CA USA

References

- Packer M. Medicare for All: Would Patients and Physicians Benefit or Lose? Medpage Today. July 10, 2019. Available at: https://www.medpagetoday.com/blogs/revolutionandrevelation/80926?xid=nl_mpt_blog2019-07-10&eun=g1127723d0r&utm_source=Sailthru&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Packer_071019&utm_term=NL_Gen_Int_Milton_Packer (accessed 7/10/19).

- CMS. National Healthcare Expenditure Data. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nationalhealthaccountshistorical.html (accessed 7/11/19).

- Berchick ER, Hood E, Barnett JC. Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2017. September 12, 2018. United States Census Bureau Report Number P60-264. Available at: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-264.html (accessed 7/11/19).

- Gonzales S, Sawyer B. How does infant mortality in the U.S. compare to other countries? Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker. July 7, 2017. Available at: https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/infant-mortality-u-s-compare-countries/#item-start (accessed 7/11/19).

- Gonzales S, Ramirez M, Sawyer B. How does U.S. life expectancy compare to other countries? Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker. April 4, 2019. Available at: https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/u-s-life-expectancy-compare-countries/#item-start (accessed 7/11/19).

Cite as: Robbins RA, Wang AC. Medicare for all-good idea or political death? Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2019;19(1):18-20. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc051-19 PDF