Medical Image of the Month: Perforated Gangrenous Cholecystitis

Sunday, May 2, 2021 at 8:00AM

Sunday, May 2, 2021 at 8:00AM

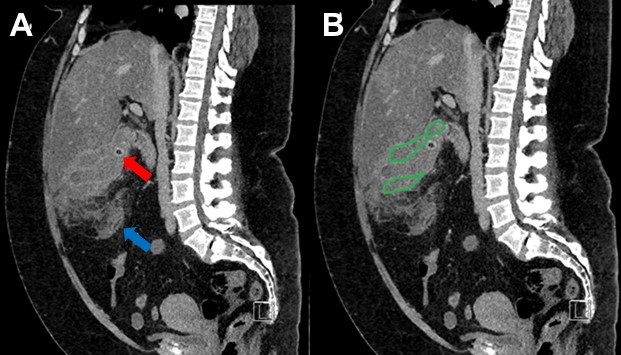

Figure 1. A sagittal CT of the abdomen and pelvis without intravenous contrast demonstrates a low-density stone in the neck of the gallbladder (red arrow) along with large amount of complex fluid adjacent to the gallbladder (outlined in green) consistent with a large pericholecystic abscess. A large amount of fat-stranding in the adjacent mesenteric fat is also noted (blue arrow).

Clinical Scenario: A 47-year-old lady with a past medical history of hypertension, DVT on Xarelto, and methamphetamine use presented with a 3-day history of progressive right upper quadrant pain. Physical examination demonstrated marked right upper quadrant tenderness with palpation and significant rebound tenderness. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis without intravenous contrast demonstrated findings consistent with acute calculus cholecystitis with evidence of perforation and a pericholecystic abscess. The patient was taken emergently to the operating room where she underwent an open cholecystectomy which demonstrated perforated gangrenous cholecystitis with a large abscess in the gallbladder fossa. She was admitted to the ICU post-operatively due septic shock and did well with fluid resuscitation and antibiotic administration.

Discussion: Acute cholecystitis is the most common acute complication of cholelithiasis and accounts for 3-9% of hospital admissions for acute abdominal pain. Eight to 95% of cases of acute cholecystitis are the result of a stone obstructing the cystic duct or gallbladder neck. Acute acalculous cholecystitis accounts for the remaining 5-20% of cases of cholecystitis. Ultrasound is the preferred initial examination for patients suspected of having cholecystitis. Gangrenous cholecystitis is the most common complication of acute cholecystitis and often necessitates emergent surgery. Perforated cholecystitis is most commonly seen in association with gangrenous cholecystitis. Perforation most commonly occurs at the gallbladder fundus where blood flow to the gallbladder is most distal.

Lauren Blackley, AG-ACNP-S1

Madhav Chopra MD2

Tammer El-Aini MD2

1Grand Canyon University- College of Nursing

2Banner University Medical Center – Main Campus, Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care

Reference

- Ratanaprasatporn L, Uyeda JW, Wortman JR, Richardson I, Sodickson AD. Multimodality Imaging, including Dual-Energy CT, in the Evaluation of Gallbladder Disease. Radiographics. 2018 Jan-Feb;38(1):75-89. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Blackley L, Chopra M, El-Aini T. Medical Image of the Month: Perforated Gangrenous Cholecystitis. Southwest Journal of Pulmonary and Critical Care. 2021;22(5):100-1. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc010-21 PDF