Medical Image of the Month: Diffuse White Matter Microhemorrhages Secondary to SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Infection

Tuesday, February 2, 2021 at 10:00AM

Tuesday, February 2, 2021 at 10:00AM

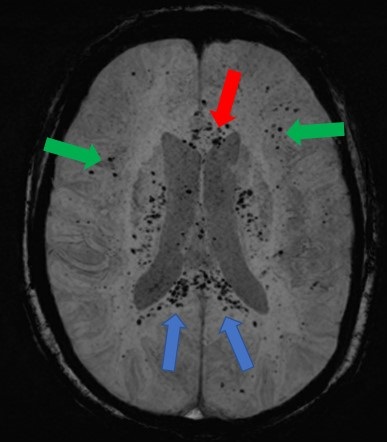

Figure 1. An axial, maximal intensity projection (MIP), susceptibility weighted image (SWI) of the brain demonstrates numerous, punctate foci of susceptibility artifact in the genu (red arrow) and splenium of the corpus callosum (blue arrows). Other foci of susceptibility artifact are seen in the juxtacortical white matter (green arrows). These foci are consistent with microhemorrhages.

Clinical Scenario: A 59-year-old woman with hypothyroidism presented to the emergency room with progressive shortness of breath for 2 weeks. Upon arrival, she was markedly hypoxic necessitating use of a non-rebreather to maintain her oxygen saturations above 88%. A chest radiograph demonstrated extensive, bilateral airspace disease. She was diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pneumonia and started on the appropriate therapies. Approximately 48 hours into her hospitalization, she required intubation with mechanical ventilation due to her progressive hypoxemic respiratory failure. She was intubated for approximately 5 weeks with a gradual improvement in her respiratory status, but not to the point where she was a candidate for a tracheostomy. Despite being off sedation for an extended period, she remained unresponsive. A CT of the head without contrast did not demonstrate any significant abnormalities. An MRI of the brain was subsequently performed and demonstrated diffuse juxtacortical and callosal white matter microhemorrhages (Figure 1). Given her persistent encephalopathy and marked respiratory failure, her family elected to pursue comfort measures.

Discussion: In a recent retrospective analysis of brain MRI findings in patients with severe COVID-19 infections, 24% of the patients had extensive and isolated white matter microhemorrhages. White matter microhemorrhages with a predominant distribution in the juxtacortical white matter and corpus callosum are nonspecific and thought to be related to hypoxia. Alternatively, small vessel vasculitis possibility related to a SARS-CoV-2 infection may result in this pattern of microhemorrhagic disease. Diffuse axonal injury (DAI) is another etiology for microhemorrhagic disease distributed in the juxtacortical white matter and corpus callosum. However, DAI is secondary to a deceleration-type injury in the setting of trauma which is not present in most patients presenting with a SARS-CoV-2 infection. The prognosis of this condition remains to be determined.

Kelly Wickstrom, DO1, Nicholas Blackstone MD2, Afshin Sam MD1, Tammer El-Aini MD1

1Banner University Medical Center – Tucson Campus, Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care, Tucson, AZ USA

2Banner University Medical Center – South Campus, Department of Internal Medicine, Tucson, AZ USA

References

- Kremer S, Lersy F, de Sèze J, et al. Brain MRI Findings in Severe COVID-19: A Retrospective Observational Study. Radiology 2020: 297: E242-E251. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radmanesh A, Derman A, Lui Y et al. COVID-19-associated Diffuse Leukoencephalopathy and Microhemorrhages. Radiology. 2020 Oct;297(1):E223-E227. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Wickstrom K, Blackstone N, Sam A, El-Aini T. Medical Image of the Month: Diffuse White Matter Microhemorrhages Secondary to SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Infection. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2021;22(2):56-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc001-21 PDF