John N. Galgiani, MD

Valley Fever Center for Excellence

The University of Arizona Colleges of Medicine

Tucson and Phoenix, Arizona

Introduction

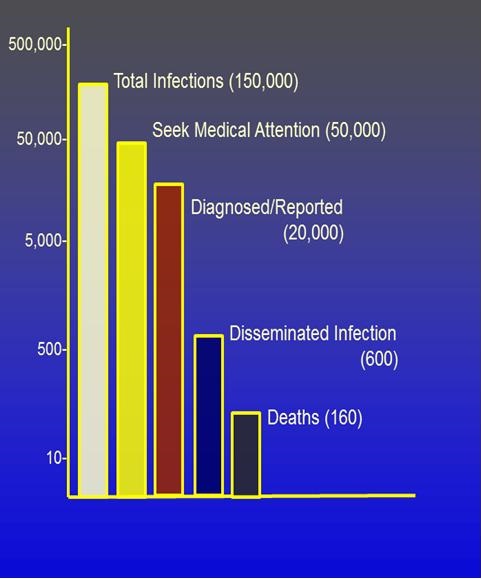

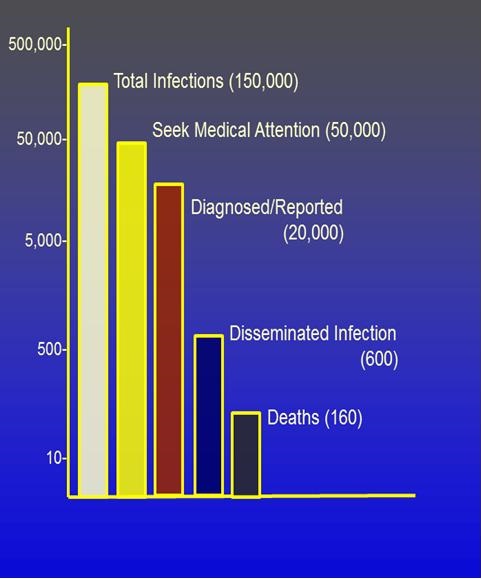

Of the roughly 150,000 new infections of coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever) that occur each year, there is an enormous range of severity and outcomes. As depicted in Figure 1, approximately a third seek medical attention because of a significant illness and even fewer of these are accurately diagnosed and reported to state officials (1).

Figure 1. Severity and outcomes of coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever).

The community-acquired pneumonia syndrome that most symptomatic patients experience often takes many weeks to many months to completely resolve and is anything but trivial (2). Even so, for most patients, the illness is eventually self-limited whether treated or not.

In contrast, a relatively small proportion of all infections result in the spread through the blood stream beyond the lungs (extrathoracic dissemination) to produce progressive tissue destruction in skin, bones, joints, the central nervous system, and almost any other part of the body. As a result, about 160 persons die of Valley Fever each year (3). What accounts for this striking spectrum of disease has been the subject of speculation for decades. Now two research programs have been initiated to try to answer this question.

Genetic Differences Among Persons Is The Prime Suspect

For many infectious diseases, the size of the microbial inoculum determines whether disease will result. Indeed, there are very good examples of this when the exposure to coccidioidal spores is very high. For example, when archeologists or construction projects involve soil rich in spores of Coccidioides spp., infection rates are higher and symptomatic illness is more common than found in the general population within endemic regions (4-6). However, in such clusters, there is little or no evidence that high inoculum is more likely to result in extrathoracic dissemination.

Another possible source of differences in disease severity could be due to differences among strains of Coccidioides spp. While this cannot be entirely ruled out, the evidence that exists is not supportive. For example, in the clusters of infections cited above where likely most infections came from genetically similar spores, there is still a wide spectrum of illness. Similarly, in laboratory accidents where all persons are definitely exposed to the same strain, there are also diverse clinical manifestations (7).

In contrast to inoculum and fungal virulence, several lines of evidence implicate genetic differences among individuals as a factor responsible for disseminated infection. First and most apparent, normal control of coccidioidal infection is critically dependent on competent cellular immunity. When this is severely compromised either by an underlying disease such as AIDS (8, 9) or by immunosuppression for organ transplantation or treatment of autoimmune disorders (10-12), coccidioidal infections are very much more likely to result in extrathoracic dissemination. That broad immunosuppression is a major risk factor for disseminated Valley Fever opens up the possibility that more subtle differences in the immune response to coccidioidal infection could account for differences in disease severity.

Secondly, men are much more likely to develop disseminated coccidioidal infection than women. Evidence for this comes from the enrollment statistics for clinical trials conducted by the Mycoses Study Group for patients with disseminated coccidioidal infection where between 1988 and 2007 three-quarters of 367 subjects were male (13-17). Similar results are apparent in other reports as well (18-20).

Thirdly, at least one specific genetic marker, that of B and AB blood groups, has been associated with disseminated infection (19, 21). This is not likely to be a causal relationship but does clearly suggest a genetic component.

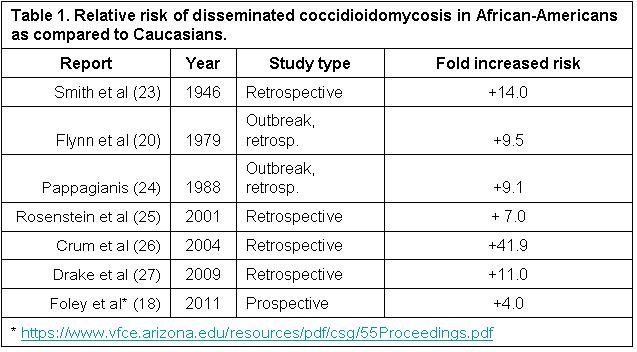

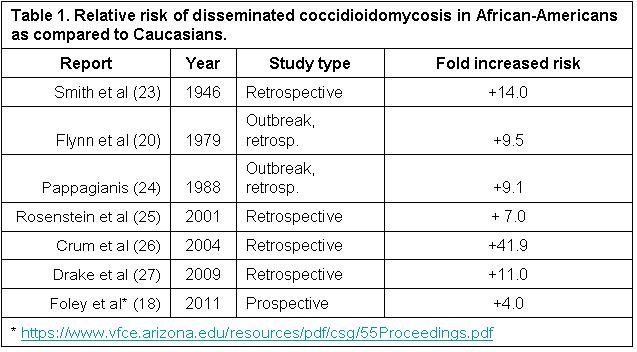

Finally, numerous studies have implicated increased risk of certain ethnic groups for disseminated infection, most notably those of African and Filipino ancestry (22). Estimates of how much more susceptible African-Americans are to developing disseminated disease range as high as 41.9 times more than Caucasians (Table 1).

An Arizona Department of Health Services presentation in 2011 based upon chart review of reported cases found dissemination in Blacks was 25% compared to 6% in Whites, roughly a four-fold increase in incidence of dissemination. The denominator for these statistics was all cases reported to the state and therefore avoid referral bias and some other confounding factors in earlier studies.

Despite all of these associations suggesting a genetic component to a risk for disseminated infection, there have been essentially no observations as to which specific genes are involved and how genetic differences affect disease susceptibility. Dr. Stephen Holland, a physician scientist and his colleagues at the National Institutes for Health have recently identified in a small number of patients specific gene mutations which appear responsible for more severe infections. The mutated genes were the interferon-gamma receptor 1 (28), the interleukin-12 receptor beta (29), and STAT1 (30).

As important as these findings are, all of the patients described in these reports are not typical of most patients who experience disseminated coccidioidomycosis. The patient with the interferon-gamma receptor 1 deficiency had two other opportunistic mycobacterial infections at other times in his life, and multiple opportunistic infections are not typical for patients with disseminated Valley Fever. The patients with the interleukin-12 beta deficiency were siblings from a consanguineous family. Disseminated coccidioidomycosis is very uncommon in multiple members of the same family. The two patients with the STAT1 mutation had a clinical presentation that included disseminated infection but also included a consumptive pulmonary process that was strikingly devoid of cavitation. However, Dr. Holland has identified additional patients who appear to have functional immunologic deficits, even thought he and his team were unable to determine the genetic basis for those altered responses (31).

Two Studies Now Underway Involving Arizonans To Better Understand The Genetics Of Disseminated Valley Fever

Encouraged by his recent findings, Dr. Holland has written a clinical research protocol specifically addressing patients with disseminated coccidioidomycosis. The program, entitled “The Pathogenesis and Genetics of Disseminated Coccidioidomycosis,” is open to any person over the age of 2 years who has culture or histologic proof of disseminated Valley Fever. Persons who have an already identified immunosuppressing condition or who have a medical or psychiatric condition that would interfere with providing informed consent would not be appropriate for this study. If informed consent is given, subjects will initially have blood specimens collected locally for shipment to the NIH. Then, depending upon initial results, subjects may be invited to visit the NIH for additional testing. After the initial visit, study related expenses, including travel and treatment of the disseminated Valley Fever infection, will be paid by the NIH (initial travel expenses may be covered for indigent subjects). Dr. Holland’s study is open to patients throughout the United States. However, for those close enough to down town Phoenix, it will be possible to have the initial blood and urine specimens obtained and shipment arranged by the NIH laboratory located on the Indian Health Hospital campus. This protocol was initiated in the fall of 2014 and is currently active.

A second research initiative is investigating the increased susceptibility of those with African ancestry. Despite the findings shown in Table 1 above, an underlying problem with all estimates of increased frequency of disseminated coccidioidomycosis in African-Americans is that the relation of self-identified race/ethnicity (SIRE) is a poor surrogate for ancestral genetic origins. Genetic heterogeneity within each racial and ethnic grouping may bias associations in genetic association studies, generating both false-positive and false-negative results (32-36). Variations in the distribution of single nucleotides polymorphisms (SNPs), called ancestry informative markers (AIMs), have been found which describe the architecture of genome variations between populations (37). This discovery has led to an approach which circumvents the genetic ambiguity of SIRE categorizations. One of the benefits of AIMs is that relatively few markers are required (about 1,500 AIMs for African-Americans) to effectively screen the entire genome. As such, we expect it to identify large chromosomal regions of differential ethnic ancestry in clinical samples.

For this second study, anyone who is self-declared of African ancestry who has laboratory confirmed coccidioidal infection is eligible. For those who have not experienced disseminated infection, an adequate length of time off antifungal therapy is necessary (nominally two years (38)) to determine if disseminated infection is not likely to occur. Consenting subjects will be asked for a sample of saliva for genetic testing. They may also be asked for a blood specimen in the future for laboratory studies of their leukocyte response to coccidioidal antigens. Collaborators for this study are in both Phoenix and in Tucson.

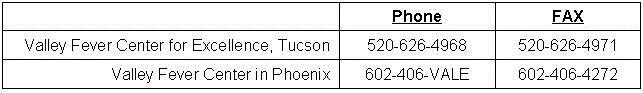

Any Arizona clinician interested in referring a patient for potential inclusion in either study can contact the Valley Fever Center for Excellence at the Arizona Health Sciences Center in Tucson or the Valley Fever Center in Phoenix located at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center at their respective phone or FAX contact numbers:

Summary

After decades of interest and speculation about what possible genetic influences are involved in determining the severity of Valley Fever infections, there are now two separate studies underway to address this question, each taking a different and complementary approach. At the very least, such information would be valuable for risk stratification, either for persons wanting that information before travelling to the coccidioidal endemic area or early in the course of a new coccidioidal infection. However, depending upon the success of this research, understanding the genetics could possibly suggest new therapeutic options. Most helped by this work will be Arizonans where two-thirds of all Valley Fever infections in the United States occur.

References

- CDC. Increase in reported coccidioidomycosis - United States, 1998-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:217-21. [PubMed]

- Tsang CA, Anderson SM, Imholte SB, Erhart LM, Chen S, Park BJ, et al. Enhanced surveillance of coccidioidomycosis, Arizona, USA, 2007-2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(11):1738-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang JY, Bristow B, Shafir S, Sorvillo F. Coccidioidomycosis-associated Deaths, United States, 1990-2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(11):1723-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner SB, Pappagianis D, Heindl I, Mickel A. An epidemic of coccidioidomycosis among archeology students in northern California. N Engl J Med. 1972;286:507-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coccidioidomycosis in travelers returning from Mexico--Pennsylvania, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49(44):1004-6. [PubMed]

- Cairns L, Blythe D, Kao A, Pappagianis D, Kaufman L, Kobayashi J, et al. Outbreak of coccidioidomycosis in Washington State residents returning from Mexico. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2000;30(1):61-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens DA, Clemons KV, Levine HB, Pappagianis D, Baron EJ, Hamilton JR, et al. Expert opinion: what to do when there is Coccidioides exposure in a laboratory. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(6):919-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fish DG, Ampel NM, Galgiani JN, Dols CL, Kelly PC, Johnson CH, et al. Coccidioidomycosis during human immunodeficiency virus infection. A review of 77 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1990;69:384-91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh VR, Smith DK, Lawerence J, Kelly PC, Thomas AR, Spitz B, et al. Coccidioidomycosis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: Review of 91 cases at a single institution. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23(3):563-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taroumian S, Knowles SL, Lisse JR, Yanes J, Ampel NM, Vaz A, et al. Management of coccidioidomycosis in patients receiving biologic response modifiers or disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(12):1903-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vucicevic D, Carey EJ, Blair JE. Coccidioidomycosis in liver transplant recipients in an endemic area. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(1):111-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vikram HR, Blair JE. Coccidioidomycosis in transplant recipients: a primer for clinicians in nonendemic areas. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14(6):606-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galgiani JN, Stevens DA, Graybill JR, Dismukes WE, Cloud GA. Ketoconazole therapy of progressive coccidioidomycosis. Comparison of 400- and 800-mg doses and observations at higher doses. Am J Med. 1988;84(3 Pt 2):603-10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graybill JR, Stevens DA, Galgiani JN, Dismukes WE, Cloud GA, NAIAD Mycoses Study Group. Itraconazole treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Am J Med. 1990;89:282-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galgiani JN, Catanzaro A, Cloud GA, Higgs J, Friedman BA, Larsen RA, et al. Fluconazole therapy for coccidioidal meningitis. The NIAID-Mycoses Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(1):28-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galgiani JN, Catanzaro A, Cloud GA, Johnson RH, Williams PL, Mirels LF, et al. Comparison of oral fluconazole and itraconazole for progressive, nonmeningeal coccidioidomycosis. A randomized, double-blind trial. Mycoses Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(9):676-86. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catanzaro A, Cloud GA, Stevens DA, Levine BE, Williams PL, Johnson RH, et al. Safety, tolerance, and efficacy of posaconazole therapy in patients with nonmeningeal disseminated or chronic pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(5):562-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley CGT, C.A.;Christ,C.;Anderson,S.M. Impact of disseminated coccidioidomycosis in Arizona, 2007-2008. Proceedings of the 55th Annual Coccidioidomycosis Study Group. University of California at Davis, Davis California: Coccidioidomycosis Study Group; 2011:8.

- Cohen IM, Galgiani JN, Potter D, Ogden DA. Coccidioidomycosis in renal replacement therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142:489-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn NM, Hoeprich PD, Kawachi MM, Lee KK, Lawrence RM, Goldstein E, et al. An unusual outbreak of windborne coccidioidomycosis. N Engl J Med. 1979;301(7):358-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deresinski SC, Pappagianis D, Stevens DA. Association of ABO blood group and outcome of coccidioidal infection. Sabouraudia. 1979;17:261-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappagianis D, Lindsay S, Beall S, Williams P. Ethnic background and the clinical course of coccidioidomycosis [letter]. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;120:959-61. [PubMed]

- Smith CE, Beard RR, Whiting EG, Rosenberger HG. Varieties of coccidioidal infection in relation to the epidemiology and control of the disease. Am J Public Health. 1946;36:1394-402. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappagianis D. Epidemiology of coccidioidomycosis. Curr Top Med Mycol. 1988;2:199-238. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenstein NE, Emery KW, Werner SB, Kao A, Johnson R, Rogers D, et al. Risk factors for severe pulmonary and disseminated coccidioidomycosis: Kern County, California, 1995-1996. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(5):708-15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crum NF, Lederman ER, Stafford CM, Parrish JS, Wallace MR. Coccidioidomycosis: A Descriptive Survey of a Reemerging Disease. Clinical Characteristics and Current Controversies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004;83(3):149-75. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drake KW, Adam RD. Coccidioidal meningitis and brain abscesses: analysis of 71 cases at a referral center. Neurology. 2009;73(21):1780-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinh DC, Masannat F, Dzioba RB, Galgiani JN, Holland SM. Refractory disseminated coccidioidomycosis and mycobacteriosis in interferon-gamma receptor 1 deficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(6):e62-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinh DC. Coccidioidal meningitis: disseminated disease in patients without HIV/AIDS. Medicine (Baltimore). 2011;90(1):87. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampaio EP, Hsu AP, Pechacek J, Bax HI, Dias DL, Paulson ML, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) gain-of-function mutations and disseminated coccidioidomycosis and histoplasmosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(6):1624-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duplessis CA, Tilley D, Bavaro M, Hale B, Holland SM. Two cases illustrating successful adjunctive interferon-gamma immunotherapy in refractory disseminated coccidioidomycosis. J Infect. 2011;63(3):223-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonilla C, Boxill LA, Donald SA, Williams T, Sylvester N, Parra EJ, et al. The 8818G allele of the agouti signaling protein (ASIP) gene is ancestral and is associated with darker skin color in African Americans. Hum Genet. 2005;116(5):402-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caulfield T, Fullerton SM, Ali-Khan SE, Arbour L, Burchard EG, Cooper RS, et al. Race and ancestry in biomedical research: exploring the challenges. Genome Med. 2009;1(1):8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhry S, Coyle NE, Tang H, Salari K, Lind D, Clark SL, et al. Population stratification confounds genetic association studies among Latinos. Hum Genet. 2006;118(5):652-64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shriver MD, Parra EJ, Dios S, Bonilla C, Norton H, Jovel C, et al. Skin pigmentation, biogeographical ancestry and admixture mapping. Human Genet. 2003;112(4):387-99. [PubMed]

- Tsai HJ, Choudhry S, Naqvi M, Rodriguez-Cintron W, Burchard EG, Ziv E. Comparison of three methods to estimate genetic ancestry and control for stratification in genetic association studies among admixed populations. Hum Genet. 2005;118(3-4):424-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittles RA, Weiss KM. Race, ancestry, and genes: implications for defining disease risk. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2003;4:33-67. [Pubmed]

- Ampel NM, Giblin A, Mourani JP, Galgiani JN. Factors and outcomes associated with the decision to treat primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(2):172-8. [CrossRef]

Reference as: Galgiani JN. How does genetics influence valley fever? research underway now to answer this question. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2014;9(4):230-7. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc137-14 PDF

Sunday, February 1, 2015 at 8:00AM

Sunday, February 1, 2015 at 8:00AM