Nathan Spence, MD

Karen Niehaus, MD

Leonardo Macias, MD

Bart Cox, MD

University of New Mexico Hospital

Albuquerque, New Mexico, United States

Introduction

First described by Saltykow in 1905 (1), Giant cell myocarditis (GCM) is a rare but highly lethal disease. Until the 1980s the diagnosis of GCM was determined at autopsy (2). It often affects young patients (mean age of 42.6 + 12.7 years), and appears to occur in men and women equally. The occurrence of GCM in minority patients has not been previously described (3). The most common presenting symptom is heart failure (75%), though ventricular tachycardia (14%), chest pain with ECG findings of acute myocardial infarction (6%) and complete heart block (5%) may also occur. Treatment often involves an immunosuppressive regimen as a bridge to heart transplantation. The prevalence of GCM is known primarily from autopsy studies (i.e., 0.051% in India, 0.007% in England, and 0.023% in Japan) (4-6). In the largest GCM observational study yet published, the rate of death or cardiac transplantation was 89 percent, with a median survival of 5.5 months from the onset of symptoms to the time of death or transplantation (3). Few cases with the successful treatment of GCM have been reported (7). Here we describe a case of GCM in a Hispanic female, the first to our knowledge, in which immediate diagnosis and initiation of an immunosuppressive regimen led to a favorable hospital course, whereby she was clinically stabilized and able to be transferred for transplant evaluation.

Case

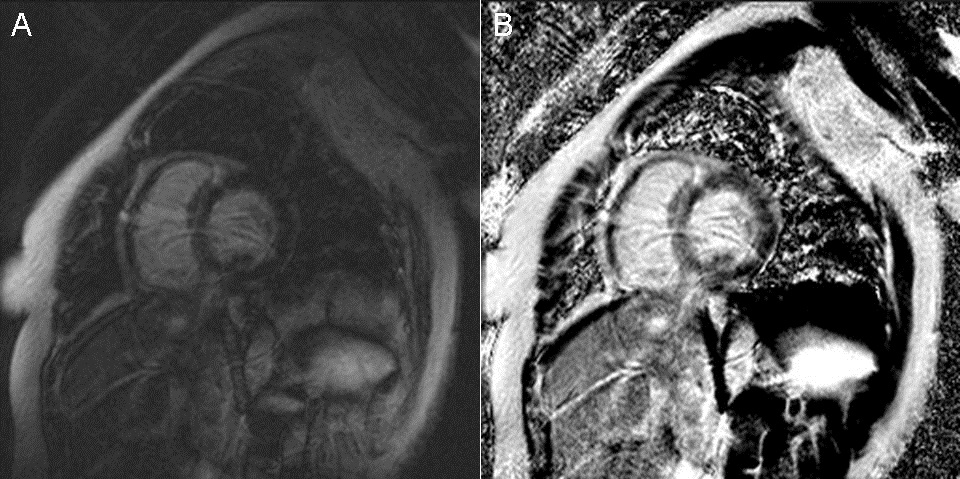

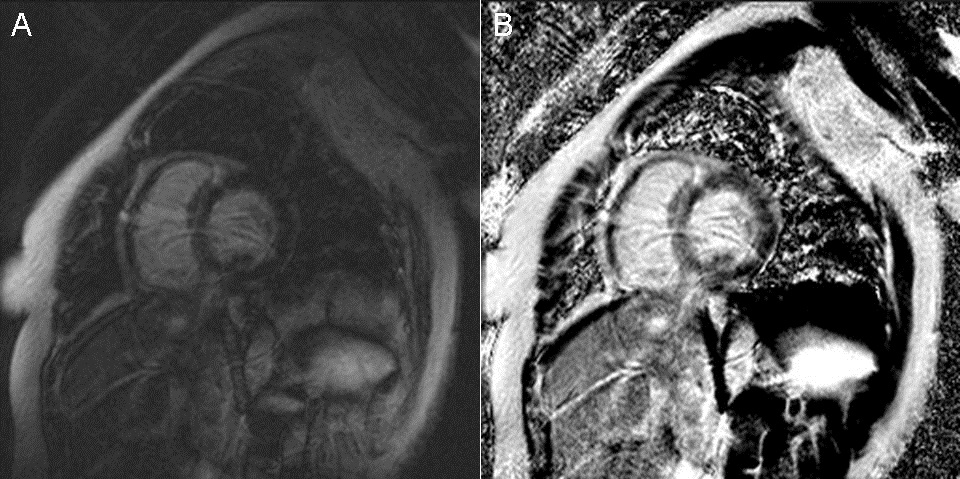

A 56-year-old Hispanic female with a past medical history significant only for hypertension presented to our emergency department for evaluation of a non-productive cough over the last 3 days, which was associated with a headache, runny nose, myalgias, nausea, vomiting, chest pain, increased dyspnea on exertion, and lower extremity edema. On initial evaluation, heart rate was 86, blood pressure was 131/84, temperature was 37.4 degrees Celsius, oxygen saturation 96% on room air. Physical exam revealed a patient in moderate distress, a pericardial friction rub, clear lungs, and trace lower extremity edema. Laboratory testing revealed a leukocytosis of 12,800/mm3 (normal < 10,600/mm3), troponin I of 3.020 ng/mL (normal < 0.06 ng/mL), N-Terminal-Pro-BNP of 9,775 pg/mL (normal < 125 pg/mL), elevated ESR of 43 mm/hr (normal < 15mm/hr), elevated CRP of 3.6mg/dL (normal < 1 mg/dL), and a mild eosinophilia of 6% (normal < 5%). Respiratory viral panel was negative. Chest X-Ray revealed a globular cardiac silhouette without definite evidence of congestion. Twelve-lead electrocardiogram revealed normal sinus rhythm with a new left bundle branch block. Cardiac catheterization revealed no significant coronary stenosis, with a left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP) of 22 mmHg. Upon admission to the floor, diuresis and titration of guideline based medications for dilated cardiomyopathy were begun, but were promptly discontinued due to development of hypotension. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) displayed severe hypokinesis of the basal inferoseptum and inferior wall of the left ventricle. Estimated ejection fraction was 35%, with mild to moderate mitral regurgitation. Blood pressure stabilized on day 2 of admission. Cardiac MR (CMR) with gadolinium was ordered, which did not show definite myocardial delayed enhancement (i.e., no evidence of infarction, myocarditis. See Figure 1).

Figure 1 Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging. (A) Two chamber delayed post-gadolinium inversion recovery view. (B) Two chamber delayed post-gadolinium phase sensitive inversion recovery view.

On day 3 of hospitalization, the patient suddenly developed complete heart block, became hypotensive and confused. As a result, a temporary venous pacemaker (TVP) was placed, and endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) was performed. Five specimens were obtained. Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was measured at 32 mmHg, with a Fick cardiac output 3.01 L/min and cardiac index of 1.77 L/min/m2. Due to persistent hypotension in the cath lab, a dopamine drip was begun, a Swan-Ganz catheter was placed, and the patient was transferred to the Medical Intensive Care Unit for further hemodynamic monitoring and treatment. That afternoon, GCM was diagnosed by pathology (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Pathology. (A) Infiltration of cardiac muscle tissue by an inflammatory infiltrate. (B) Massive myocyte necrosis with giant cells among the inflammatory infiltrate. (C) Rare eosinophils are seen among the inflammatory infiltrate. (D) Giant cell among the inflammatory infiltrate.

An immunosuppressive regimen of corticosteroids, azathioprine, and cyclosporine was promptly initiated. Thereafter, over the course of 3 days, clinical symptoms and hemodynamics improved significantly. TVP was removed, inotropic support was weaned off, and ACE inhibitor and diuretics were titrated. Beta-blockers were withheld out of concern for recent complete heart block and use of inotropic support. On hospital day 10, the patient was transferred, in stable condition, to be evaluated for heart transplantation, and/or mechanical circulatory support. At the outside center, she had an ICD placed for primary prevention, was maintained on the three drug immunosuppression regimen, continued to do well clinically, and was listed for transplant.

Discussion

Several autoimmune disorders have been associated with GCM, which include inflammatory bowel disease, thyroiditis, and thymoma (8). Our patient did not have a history of autoimmune disease, and the laboratory tests to detect such during her hospitalization were negative. Evidence suggests that GCM is an autoimmune disorder dependent on CD4-positive T lymphocytes and anti-myosin autoantibodies (8). Early diagnosis leading to appropriate treatment, as in our case, appears to be imperative for a favorable clinical outcome. Treatment with a combination of immunosuppressives has been shown to improve survival, compared with those not receiving immunosuppressive regimens (12.3 months vs. 3.0 months, p=0.001) (3). If patients live long enough to receive heart transplantation, longer term survival is possible. For that reason, it is a Class I (level of evidence B) guideline recommendation to perform EMB in the setting of unexplained, new-onset heart failure of < 2 weeks' duration associated with a normal sized or dilated left ventricle in addition to hemodynamic compromise (9). The sensitivity of EMB for GCM is 80% to 85% in subjects who subsequently die or undergo heart transplantation (2). Therefore, in the appropriate clinical setting, EMB may drastically alter treatment and provide important prognostic information. The pathological hallmark of GCM is the presence of multinucleated giant cells and a lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate, associated with myocyte necrosis (10-12). CMR may display delayed myocardial enhancement to support the diagnosis of myocarditis, though a non-diagnostic study, as in our case, does not rule it out.

We encountered, to our knowledge, the first case of GCM in a patient of Hispanic ethnicity, who presented with the classic associated symptoms of heart failure, hemodynamic collapse, and complete heart block, and whose clinical course was favorably improved by early diagnosis and initiation of an immunosuppressive regimen. CMR did not identify myocarditis. However, this case illustrates the importance of including GCM in the differential diagnosis when a patient presents with suggestive clinical features and is not responding to current evidence based treatment for acute decompensated heart failure.

References

- Saltykow S. Uber Diffuse Myokarditis. Virchows Archiv fur Pathologische Anatomie. 1905;182:1-39. [CrossRef]

- Shields RC, Tazelaar HD, Berry GJ, Cooper LT. The role of right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy for idiopathic giant cell myocarditis. J Card Fail. 2002;8:74-88. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper LT, Berry GJ, Shabetai R. Idiopathic giant-cell myocarditis - natural history and treatment. Multicenter Giant Cell Myocarditis Study Group Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1860-6.[CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaideeswar P, Cooper L. Giant cell myocarditis: clinical and pathological disease characteristics in an indian population. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2013;22:70-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead R. Isolated myocarditis. Brit Heart J 1965;27:220-30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada R, Wakafuji S. Myocarditis in autopsy. Heart Vessels 1985; Suppl 1:23-9. [CrossRef]

- Desjardins V, Pelletier G, Leung TK, Waters D. Successful treatment of severe heart failure caused by idiopathic giant cell myocarditis. Can J Cardiol. 1992;8:788-92. [PubMed]

- Cooper L, ElAmm C. Giant Cell Myocarditis: Diagnosis and treatment. Herz. 2012;37:632-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper LT, Baughman KL, Feldman AM, et al. The role of endomyocardial biopsy in the management of cardiovascular disease. A scientific statement from the American heart association, the American college of cardiology, and the European society of cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(19):1914-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies M, Pomerance A, Teare R. Idiopathic giant cell myocarditis - a distinctive clinico-pathological entity. Br Heart J. 1975;37:192-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidoff R, Palacios I, Southern J, Fallon JT, Newell J, Dec GW. Giant cell versus lymphocytic myocarditis. A comparison of their clinical features and long-term outcomes. Circulation. 1991;83:953-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren H, Poston RS Jr, Hruban RH, Baumgartner WA, Baughman KL, Hutchins GM. Long survival with giant cell myocarditis. Mod Pathol. 1993;6:402-7. [PubMed]

Reference as: Spence N, Niehaus K, Macias L, Cox B. Giant cell myocarditis: a case report and review of the literature. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2014;8(4):247-51. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc052-14 PDF

Tuesday, July 1, 2014 at 8:00AM

Tuesday, July 1, 2014 at 8:00AM