Yield and Complications of Endobronchial Ultrasound Using the Expect Endobronchial Ultrasound Needle

Thursday, June 6, 2024 at 8:00AM

Thursday, June 6, 2024 at 8:00AM Fatima Ghazal1, Sandrine Hanna2, Christy Costanian3, Shashank Nuguru4, and Khalil Diab2

1Department of Internal Medicine, University of Connecticut Health Center, 263 Farmington Ave, Farmington, CT USA

2Department of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC USA

3Department of Biostatistics, The Lebanese American University Gilbert and Rose-Marie Chagoury School of Medicine, Byblos, Lebanon

4Department of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Wellstar Kennstone, Atlanta, GA USA

Abstract

Background: Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) stands as the gold standard for sampling the mediastinum and possesses the capability to detect a diverse range of disease processes. The EBUS needle industry has been experiencing rapid advancement, characterized by numerous companies either enhancing existing needles or introducing innovative ones. The majority of EBUS studies to date have predominantly utilized the OlympusTM Vizishot needles, which are constructed from stainless steel. In this paper, we focus on the evaluation of a cobalt chromium needle, namely the ExpectTM EBUS needle, with a specific emphasis on its diagnostic efficacy and any associated complications. It is important to note that our investigation is conducted independently, and we do not provide a comparative analysis with other needle types available in the market.

Methods: This is an institutional review board-approved retrospective analysis of all patients who have undergone an EBUS-TBNA lymph node sampling using the ExpectTM needle between August 2016 and September 2017 at the IU Health University Hospital. Comparisons of clinical characteristics by complications, diagnosis, needle gauge, and lymph node size were performed using chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test.

Results: 75% of the 102 included patients had their procedures done with the 22-gauge needle which were majorly performed in the setting of suspected intrathoracic malignancy followed by sarcoidosis and lymphoma. 99% of the patients had no complications after their procedures which were almost all diagnostic with two cases of bronchoscope damage. Mutational analysis was successful with both the 22 and 25-Gauge needles.

Conclusion: In this paper, we demonstrate that the ExpectTM 22 and 25-gauge needles are safe and effective when used for EBUS-TBNAs through the OlympusTM EBUS bronchoscope for the evaluation of intrathoracic lymphadenopathy.

Introduction

The treatment of lung cancer has been evolving rapidly over the past several years. It is of utmost importance to secure an accurate pathological diagnosis and to adequately stage lung cancer patients prior to any treatment decision. One of the primary determinants of cancer staging is lymph node tumoral involvement which makes accurate pre-operative assessment essential. The utility of endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS)-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA) is now firmly established in sampling mediastinal lymph nodes and has become the gold standard method in place of mediastinoscopy in terms of cost-effectiveness, accuracy, and safety (1,2). More importantly, the use of EBUS-TBNA has been particularly important in upstaging tumors, especially in presumed N0 or N1 disease on initial imaging (3-6). Furthermore, in the era of targeted cancer treatment, it has also shown success in tissue sampling for molecular analysis, such as programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) analysis and other mutations (7-10).

Endobronchial ultrasound has become the gold standard for lung cancer diagnosis and staging, and its use and adoption has increased rapidly over the years. Indeed, the market share of endobronchial ultrasound needles has been growing recently with multiple companies expanding on older needles or producing new ones. Most endobronchial ultrasound studies have utilized the OlympusTM (Center Valley, PA) Vizishot needles, which are stainless steel needles (11-13). Our aim in this paper is to examine another type of needle, the ExpectTM endobronchial ultrasound needle (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA), looking at its diagnostic yield and rate of complications when used for EBUS-TBNA. This is a cobalt chromium needle with a sharp tip that has a unique locking mechanism and method of entry into the lymph nodes.

Our primary outcome is to assess the yield and specimen adequacy at different nodal stations using this specific needle. We evaluated its yield in the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer and other mediastinal diseases. The secondary objective of our study is to look at procedure-related complications pertaining to both the patients and the bronchoscope itself using the ExpectTM needle.

Materials and Methods

Patients

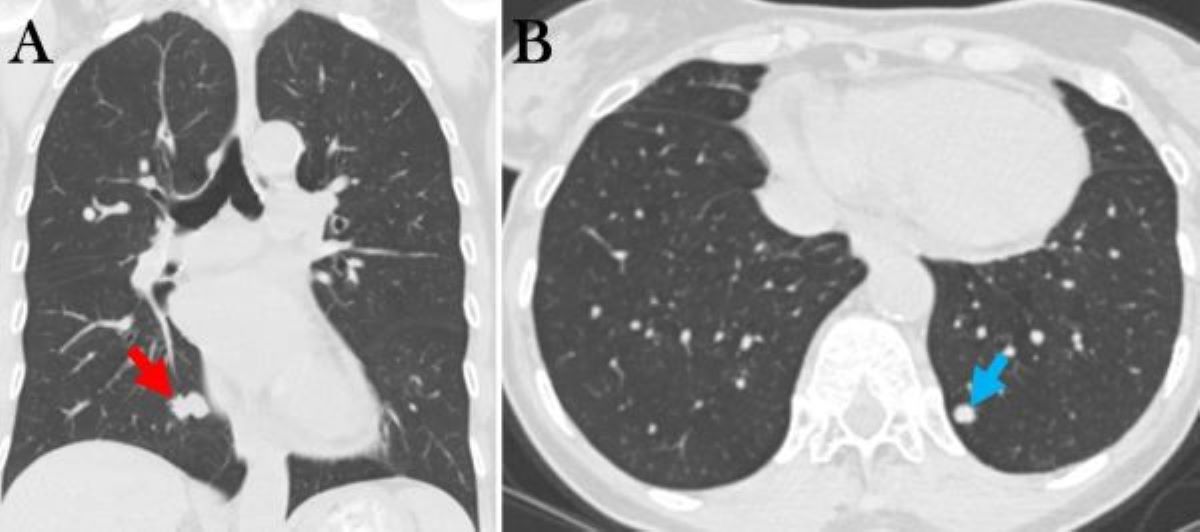

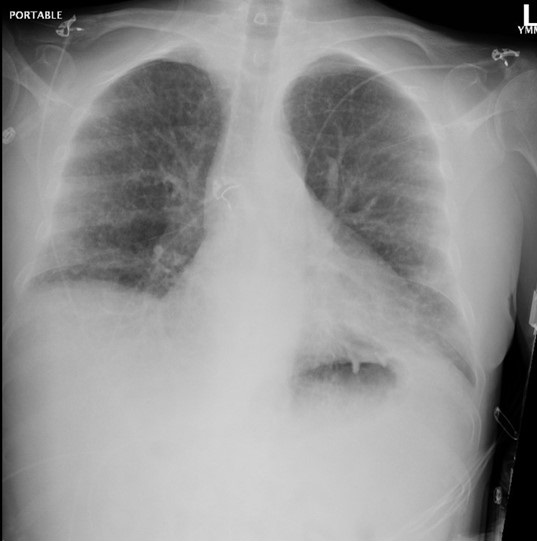

From August 2016 to September 2017, we reviewed our database of patients older than 18 years of age with mediastinal lymphadenopathy whether associated with a suspected, or confirmed lung cancer or other causes, who were referred to the Indiana University Health University Hospital for a diagnostic workup using the ExpectTM 22 and 25-gauge needles. Electronic health records were reviewed for demographic information, including age, gender, pre-procedure diagnosis, smoking status, associated comorbidities, radiographic findings with either computed tomography (CT) scan and/or Positron Emission Tomography (PET), location and size of the enlarged lymph nodes as well as their clinical course. The study was approved by the Indiana University institutional review board (study number:1610932969).

Procedure

All cases were performed in the operating room of Indiana University Health University Hospital under general anesthesia using an I-gelTM manufactured by Intersurgical (Berkshire, United Kingdom). The cases were performed by the same interventional pulmonologist in the presence of a pulmonary fellow. Prior to the procedure, a CT scan of the chest and reports of prior imaging (including PET scans) were available for a final review of the lymph nodes. Those lymph nodes to be sampled were selected based on appropriate lung cancer staging in cases of suspected lung cancer, or for diagnosis of other benign and malignant mediastinal nodal diseases. After introduction in the trachea, the bronchoscope was advanced to the main carina and the lymph nodes were examined sequentially. For all visualized lymph nodes, an EBUS image was obtained with the sizes measured prior to nodal puncture. After selection of the lymph node to be sampled, the airway mucosa was punctured under continuous ultrasound guidance using the either the 22-gauge or 25-gauge Expect TM endobronchial ultrasound needle (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA). The stylette is typically pulled out several centimeters prior to puncture to expose the sharp tip of the needle, then entry into the lymph node is established. Ten actuations are done and the lymph nodes are sampled on a slide in the presence of rapid onsite cytologic evaluation. Each lymph node is sampled at least 3 times. Further sampling for cell block is done based on the cytologist’s recommendations.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze clinical characteristics and outcomes. Comparisons of clinical characteristics by complications, diagnosis, needle gauge, and lymph node size were performed using chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test, when needed. In all cases, a two-tailed p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed using STATA 13.0.

Results

A total of 102 patients were included in the analysis. Most of the patients were older than 70 years of age (more than 70%) with almost 30% aged between 51-60 years. 40% of patients were former smokers while 35% were current smokers. More than 75% of patients had their procedure performed using the 22-gauge needle and the rest using the 25-gauge needle. A lymph node size of ≥ 8mm was selected in 78.4% of cases. The most common indications for bronchoscopy were diagnosis and staging of lung cancer with mediastinal adenopathy in 61.8% of the cases, followed by sarcoidosis and lymphoma rule out in 31%., followed by work-up of mediastinal lymphadenopathy with or without lung nodules in the setting of active extra-thoracic malignancy. The overwhelming majority of patients had no complications after their procedures (99%) which were almost all diagnostic. There were only two cases of bronchoscope damage which happened when the needle was entered without the stylette.

All diagnostic procedures had no complications except one procedure complicated by a pneumomediastinum which was the only non-diagnostic case. Table 1 explores the proportion of procedures done using the 22-gauge and 25-gauge needles by diagnosis, in which all patients (100%), had adequate tissue sample for molecular testing.

Table 1. Needle Gauge by Yield or Diagnosis

*SCLC, Small cell lung cancer; **NSCLC, Non-small cell lung cancer

75-80% of lung cancer diagnoses were obtained using a 22-gauge needle, while the rest were obtained using a 25-gauge needle. 88.9% of cases with metastatic malignancy from outside the lungs were diagnosed using a 22-gauge needle. All cases of granulomatous disease (100%) and most cases of reactive lymphadenopathy were diagnosed with the 22-gauge needle. At Indiana University, reactive lymphadenopathy diagnosis was based on rapid on-site assessment and indicated the presence of adequate specimen with lymphocytes at our centre. Pneumomediastinum as a complication occurred in the only non-diagnostic case using the 22-gauge needle. Transvascular needle aspiration was performed successfully in two cases; one diagnosing small cell lung cancer and the second diagnosing reactive lymphadenopathy. There was no significant difference in the diagnostic yield by the two needle gauges (98.75 vs 100%); most procedures were performed using the 22-gauge needle. There was no significant difference in yield between lymph nodes less than 8 mm in size and those greater than 8 mm in size, although most lymph nodes studied were greater than 8 mm in 89% of the cases. Hence in almost all the cases, mutational analysis was adequate using both the 22 and 25-gauge needles.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the yield and complications of the Expect TM needle with EBUS. Previous studies had assessed the yield of this needle with endoscopic ultrasound (14). The results of our study show that the Expect needle demonstrated good diagnostic yield in lymph node sampling during the evaluation of mediastinal lymphadenopathy for either suspected primary thoracic, metastatic malignancy or non- malignant disease processes. As the use of the EBUS technique has become the gold standard preferred over mediastinoscopy in the management of lung cancer and evaluation of mediastinal lymphadenopathy since the end 2000s, more EBUS related techniques are being evaluated and studied to enhance their diagnostic accuracy (15-19). Indeed, overwhelming evidence has proven the lower number of complications of this technique compared to surgical mediastinoscopy while yielding very good results.

In a review of biopsy needles for mediastinal lymph node sampling, Colella et al. (20) reviewed characteristics of an ideal needle, which mostly consisted of high level of resistance, flexibility and echogenicity for better visualization under ultrasonography. There are multiple needles in the market currently trying to meet these standards. These include the ProcoreTM needle and the SonoTip TopgainTM needle. The ExpectTM needle used in this study meets some of these characteristics, mostly attributable to the chromium-cobalt (CoCr) alloy it is made of. From a series of experimental needle trials, Keehan et al. (21) showed that the chromium-cobalt alloy was 24% harder than the tested Stainless Steel 304 (SS) indicating that these needles are more likely to conserve their sharpness and resist blunting (21). They also demonstrated greater kinking resistance and tensile properties than the SS needles. Moreover, it was shown that the needle was easily visualized on ultrasound and that upon withdrawal from the endoscope, there was less deformation of the needle itself. All of these aforementioned properties are particularly important, as several types of needle-related complications have been reported such as the release of metal particles into lymph nodes, breakage of the needles with possible migration and infectious sequelae (22-25).

As for the diagnostic properties investigated in this study, there was no significant difference between the 22 and 25-gauge needle sizes, although the 22-gauge needle was used in the majority of the cases. The overwhelming majority of prior studies have not reported significant superiority of a particular needle size though most were conducted comparing the 22 and 21 needle sizes (26-28). In a recent 2019 study published by Di Felice et al. (29) comparing the 22 and 25-gauge needle sizes, no significant difference was noted between their sample adequacy and diagnostic accuracy. Similarly, another 2021 study published by Sakaguchi et al. (30) showed that while the diagnostic yields of the 22 and 25-gauge sizes may be comparable in lung cancer, that of the 22-gauge is superior in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. While no particular needle size in the evaluation of lung cancer is certainly favoured, the need for increasing tissue sampling for molecular studies, immunophenotyping and next-generation sequencing has supported the use of larger needles (31-32).

On that same note, as the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has revolutionized with targeted therapies based on driver mutations positivity, more attention is drawn to maximize the yield of EBUS guided biopsies for tissue sampling (33-36). Using EBUS for this purpose is now well established especially for EGFR and ALK mutations testing (37-41). More recent studies have also supported the role of EBUS-guided TBNA samples for PDL-1 testing which draws more attention to enhance this technique as it becomes gold standard in both cancer diagnosis and management. In our study, we demonstrate that using the ExpectTM needle provides adequate samples for these tests (anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), receptor tyrosine kinase -1 (ROS-1), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), programmed death ligand -1 (PDL-1)), particularly useful when sent for adenocarcinoma.

As for the complication rate, it was low and similar to what has been previously described in the literature (42). Indeed, the only complication (pneumomediastinum) occurred in the one non-diagnostic case. Most of the literature supports a rate of adverse events of less than 1%. In a metanalysis including more than 9000 EBUS-FNA cases, von Barthled et al. (43) found a rate of serious adverse events of 0.05%. These comprised infectious complications as sepsis and mediastinal abscess formation, pneumothorax, and hypoxemia. Another Japanese survey that also evaluated the complications related to bronchoscope damage, described a low complication rate as well. The rate of needle breakage was reported at 0.2% while the rate of bronchoscope damage at 1.33% (42). This is similar to our rate of bronchoscope damage which was 0.98%.

Our study has several limitations. It is a retrospective review, and therefore, prone to the errors associated with such reviews. It also does not provide a head-to-head comparison with other needles. The absence of a control group in this research poses a challenge in estimating the potential clinical befits of utilizing the “expect” needle compared to various other types, including the OlympusTM needles (Vizishot and Vizishot 2). It is a single-centre study involving one interventional pulmonologist, and therefore, is operator-dependent and centre-dependent. Its strengths are that it is a rare evaluation of the needles currently on the market, and it paves the way for upcoming multi-center collaborative studies evaluating newer needles.

Conclusions

EBUS-guided biopsies have emerged as the preferred method for diagnosing and managing non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), prompting the exploration of various techniques for this purpose. We present evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of ExpectTM 22- and 25-gauge needles when employed for EBUS-TBNAs through the OlympusTM EBUS bronchoscope in the assessment of both benign and malignant intrathoracic lymphadenopathy. This contributes to the expanding body of EBUS literature, as novel techniques and needle options are continually being investigated and utilized. Nonetheless, the selection of the appropriate needle for EBUS entails numerous considerations. While effectiveness and the risk of complications remain paramount, factors such as the operator’s familiarity with the needle, its availability, and cost has substantial influence in decision making process.

References

- Lee BE, Kletsman E, Rutledge JR, Korst RJ. Utility of endobronchial ultrasound-guided mediastinal lymph node biopsy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012 Mar;143(3):585-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berania I, Kazakov J, Khereba M, Goudie E, Ferraro P, Thiffault V, Liberman M. Endoscopic Mediastinal Staging in Lung Cancer Is Superior to "Gold Standard" Surgical Staging. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016 Feb;101(2):547-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehgal IS, Agarwal R, Dhooria S, Prasad KT, Aggarwal AN. Role of EBUS TBNA in Staging of Lung Cancer: A Clinician's Perspective. J Cytol. 2019 Jan-Mar;36(1):61-64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarnecka-Kujawa K, Yasufuku K. The role of endobronchial ultrasound versus mediastinoscopy for non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2017 Mar;9(Suppl 2):S83-S97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge X, Guan W, Han F, Guo X, Jin Z. Comparison of Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Fine Needle Aspiration and Video-Assisted Mediastinoscopy for Mediastinal Staging of Lung Cancer. Lung. 2015 Oct;193(5):757-66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong TL, Loveland PM, Gorelik A, Irving L, Steinfort DP. Preoperative Staging by EBUS in cN0/N1 Lung Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2019 Jul;26(3):155-165. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raad S, Hanna N, Jalal S, Bendaly E, Zhang C, Nuguru S, Oueini H, Diab K. Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Transbronchial Needle Aspiration Use for Subclassification and Genotyping of Lung Non-Small-Cell Carcinoma. South Med J. 2018 Aug;111(8):484-488. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Olivé I, Monsó E, Andreo F, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration for identifying EGFR mutations. Eur Respir J. 2010 Feb;35(2):391-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurado J, Saqi A, Maxfield R, et al. The efficacy of EBUS-guided transbronchial needle aspiration for molecular testing in lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013 Oct;96(4):1196-1202. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakakibara R, Inamura K, Tambo Y, Ninomiya H, Kitazono S, Yanagitani N, Horiike A, Ohyanagi F, Matsuura Y, Nakao M, Mun M, Okumura S, Inase N, Nishio M, Motoi N, Ishikawa Y. EBUS-TBNA as a Promising Method for the Evaluation of Tumor PD-L1 Expression in Lung Cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2017 Sep;18(5):527-534.e1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye T, Hu H, Luo X, Chen H. The role of endobronchial ultrasound guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) for qualitative diagnosis of mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy: a prospective analysis. BMC Cancer. 2011 Mar 21;11:100. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasufuku K, Nakajima T, Motoori K, Sekine Y, Shibuya K, Hiroshima K, Fujisawa T. Comparison of endobronchial ultrasound, positron emission tomography, and CT for lymph node staging of lung cancer. Chest. 2006 Sep;130(3):710-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthi M, Donna E, Arias S, Villamizar NR, Nguyen DM, Holt GE, Mirsaeidi MS. Diagnostic Accuracy of Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Transbronchial Needle Aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) in Real Life. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020 Apr 7;7:118. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto K, Takeda Y, Onoyama T, Kawata S, Kurumi H, Koda H, Yamashita T, Isomoto H. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy - Recent topics and technical tips. World J Clin Cases. 2019 Jul 26;7(14):1775-1783. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez M, Silvestri GA. Endobronchial ultrasound for the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009 Apr 15;6(2):180-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong X, Qiu X, Liu Q, Jia J. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration in the mediastinal staging of non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013 Oct;96(4):1502-1507. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge X, Guan W, Han F, Guo X, Jin Z. Comparison of Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Fine Needle Aspiration and Video-Assisted Mediastinoscopy for Mediastinal Staging of Lung Cancer. Lung. 2015 Oct;193(5):757-66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Um SW, Kim HK, Jung SH, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound versus mediastinoscopy for mediastinal nodal staging of non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2015 Feb;10(2):331-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annema JT, van Meerbeeck JP, et al. Mediastinoscopy vs endosonography for mediastinal nodal staging of lung cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010 Nov 24;304(20):2245-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colella S, Scarlata S, Bonifazi M, Ravaglia C, Naur TMH, Pela R, Clementsen PF, Gasparini S, Poletti V. Biopsy needles for mediastinal lymph node sampling by endosonography: current knowledge and future perspectives. J Thorac Dis. 2018 Dec;10(12):6960-6968. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keehan E, Cavanagh C, Gergely V. Novel alloy for speciality needle applications. Med Device Technol. 2009 Mar-Apr;20(2):23-4, 26-7. [PubMed]

- Gounant V, Ninane V, Janson X, Colombat M, Wislez M, Grunenwald D, Bernaudin JF, Cadranel J, Fleury-Feith J. Release of metal particles from needles used for transbronchial needle aspiration. Chest. 2011 Jan;139(1):138-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özgül MA, Çetinkaya E, Tutar N, Özgül G. An unusual complication of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA): the needle breakage. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;20 Suppl:567-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asano F, Aoe M, Ohsaki Y, et al. Complications associated with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: a nationwide survey by the Japan Society for Respiratory Endoscopy. Respir Res. 2013 May 10;14(1):50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaidya PJ, Munavvar M, Leuppi JD, Mehta AC, Chhajed PN. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: Safe as it sounds. Respirology. 2017 Aug;22(6):1093-1101.[CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarmus LB, Akulian J, Lechtzin N, et al. Comparison of 21-gauge and 22-gauge aspiration needle in endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: results of the American College of Chest Physicians Quality Improvement Registry, Education, and Evaluation Registry. Chest. 2013 Apr;143(4):1036-1043. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima T, Yasufuku K, Takahashi R, et al. Comparison of 21-gauge and 22-gauge aspiration needle during endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Respirology. 2011 Jan;16(1):90-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeyabalan A, Shelley-Fraser G, Medford AR. Impact of needle gauge on characterization of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) histology samples. Respirology. 2014 Jul;19(5):735-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Felice C, Young B, Matta M. Comparison of specimen adequacy and diagnostic accuracy of a 25-gauge and 22-gauge needle in endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. J Thorac Dis. 2019 Aug;11(8):3643-3649. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakaguchi T, Inoue T, Miyazawa T, Mineshita M. Comparison of the 22-gauge and 25-gauge needles for endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Respir Investig. 2021 Mar;59(2):235-239. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy P, Gonzalez AV. Does (Needle) Size Matter?: Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Transbronchial Needle Aspiration for Mediastinal Adenopathy That Is Not Yet Diagnosed. Chest. 2022 Sep;162(3):503-504. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolters C, Darwiche K, Franzen D, et al. A Prospective, Randomized Trial for the Comparison of 19-G and 22-G Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Transbronchial Aspiration Needles; Introducing a Novel End Point of Sample Weight Corrected for Blood Content. Clin Lung Cancer. 2019 May;20(3):e265-e273. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindeman NI, Cagle PT, et al. Molecular testing guideline for selection of lung cancer patients for EGFR and ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors: guideline from the College of American Pathologists, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and Association for Molecular Pathology. J Thorac Oncol. 2013 Jul;8(7):823-59. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindeman NI, Cagle PT, Aisner DL, et al. Updated Molecular Testing Guideline for the Selection of Lung Cancer Patients for Treatment With Targeted Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: Guideline From the College of American Pathologists, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018 Mar;142(3):321-346. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reungwetwattana T, Dy GK. Targeted therapies in development for non-small cell lung cancer. J Carcinog. 2013 Dec 31;12:22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevallier M, Borgeaud M, Addeo A, Friedlaender A. Oncogenic driver mutations in non-small cell lung cancer: Past, present and future. World J Clin Oncol. 2021 Apr 24;12(4):217-237. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicek T, Ozturk A, Yılmaz A, Aktas Z, Demirag F, Akyurek N. Adequacy of EBUS-TBNA specimen for mutation analysis of lung cancer. Clin Respir J. 2019 Feb;13(2):92-97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeyabalan A, Bhatt N, Plummeridge MJ, Medford AR. Adequacy of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration samples processed as histopathological samples for genetic mutation analysis in lung adenocarcinoma. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016 Jan;4(1):119-125. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labarca G, Folch E, Jantz M, Mehta HJ, Majid A, Fernandez-Bussy S. Adequacy of Samples Obtained by Endobronchial Ultrasound with Transbronchial Needle Aspiration for Molecular Analysis in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018 Oct;15(10):1205-1216. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima T, Yasufuku K, Nakagawara A, Kimura H, Yoshino I. Multigene mutation analysis of metastatic lymph nodes in non-small cell lung cancer diagnosed by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Chest. 2011 Nov;140(5):1319-1324. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima T, Yasufuku K, Suzuki M, Hiroshima K, Kubo R, Mohammed S, Miyagi Y, Matsukuma S, Sekine Y, Fujisawa T. Assessment of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Chest. 2007 Aug;132(2):597-602. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asano F, Aoe M, Ohsaki Y, Okada Y, Sasada S, Sato S, Suzuki E, Semba H, Fukuoka K, Fujino S, Ohmori K. Complications associated with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: a nationwide survey by the Japan Society for Respiratory Endoscopy. Respir Res. 2013 May 10;14(1):50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Bartheld MB, van Breda A, Annema JT. Complication rate of endosonography (endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound): a systematic review. Respiration. 2014;87(4):343-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]