Renee L. Devor MD1,2

Harjot K. Bassi MD3

Paul Kang MPH4

Tiffany Morandi MD2

Kristi Richardson RT5

John J. Nigro MD2,6

Christine Tenaglia RT5

Chasity Wellnitz RN, BSN, MPH6

Brigham C. Willis MD1,2,7

1Division of Cardiac Critical Care, Phoenix Children’s Hospital, Phoenix, Arizona

2Department of Child Health, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Phoenix, Arizona

3Division of Critical Care, Phoenix Children’s Hospital, Phoenix, Arizona

4Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Phoenix, Arizona

5Department of Respiratory Therapy, Phoenix Children’s Hospital, Phoenix, Arizona

6Division of Cardiology, Phoenix Children’s Hospital, Phoenix, Arizona

7Department of Pediatrics, Creighton University School of Medicine, Phoenix, Arizona

Abstract

Background: Recruitment maneuvers are a dynamic process of transient increases in transpulmonary pressure intended to open unstable airless alveoli. Due to concerns regarding the hemodynamic consequences of recruitment maneuvers in children with heart disease, these maneuvers have not been widely utilized in this population. The objective of this study was to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of lung recruitment maneuvers in post-operative pediatric cardiac patients. We hypothesized that multiple recruitment maneuvers are physiologically beneficial and hemodynamically tolerated in children with congenital cardiac disease.

Methods: Retrospective chart review was conducted of post-operative cardiac surgical subjects who received recruitment maneuvers, as well as a matched control group who did not, at a Cardiac ICU in a quaternary care free-standing children’s hospital. Repetitive lung recruitment maneuvers using incremental positive end-expiratory pressure were performed. Hemodynamic and respiratory physiologic variables were recorded.

Results: Sixty-one post-operative cardiac subjects had a total of 435 lung recruitment maneuvers. Assessment of hemodynamic tolerability demonstrated no change in MAP, HR, or CVP during or after the maneuvers. There was a 28% increase in dynamic compliance following recruitment maneuvers (p <0.01, 95% CI). Specific outcomes in the 59 matched control subjects demonstrated no significant difference in length of mechanical ventilation (p = 0.26), length of hospital stay (p = 0.28), mortality (p = 0.58) or difference in occurrence of pneumothorax (p = 0.26).

Conclusions: Post-operative pediatric cardiac surgical subjects tolerated repeated lung recruitment maneuvers without significant hemodynamic changes. The maneuvers successfully improved dynamic compliance without any adverse effects.

Introduction

Mechanical ventilation is a common therapy used for pediatric patients in the intensive care unit and is frequently used for children with congenital cardiac disease following surgical repair. However, it is well known that mechanical ventilation can induce lung injury or worsen preexisting lung disease (1-3). In patients with congenital cardiac disease, it is crucial to protect the lung from injury and optimize ventilation and oxygenation due to their underlying hemodynamic and physiologic fragility (4, 5). Post-operatively, several factors including general anesthesia, cardiopulmonary bypass, atelectasis, and hypoxemia can contribute to lung dysfunction, which may lead to prolonged mechanical ventilation (6). Children with such prolonged ventilation are at a higher risk for poor overall outcome due to a variety of ventilator-associated morbidities (7, 8). Therefore, it is of practical value to protect the lungs and reduce the length of time mechanical ventilation is required.

Alveolar injury can be caused by the repetitive opening and closing of alveoli when inadequate positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is provided and this can generate shear stress within the alveoli and promote injury (9-10). Lung recruitment maneuvers have been defined as transient increases in the transpulmonary pressure used to open recruitable collapsed alveoli and increase end expiratory lung volume (11-13). Recruitment maneuvers are often considered useful in patients, especially those with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), to potentially decrease ventilator-induced lung injury by improving oxygenation and lung compliance while reducing the risk of atelectrauma by re-opening and stabilizing collapsed alveoli (11,13-18).

Increased intrathoracic pressure can affect right and left ventricular preload due to decreased venous return, changed right ventricular afterload, and altered biventricular compliance (4,10,14,19-21). This may lead to decreased stroke volume leading to short periods of hypotension, bradycardia, and impaired cardiac output, which is of significant concern in patients with congenital cardiac disease (14). Many patients with congenital cardiac disease must undergo surgical procedures which lead to lung collapse after induction of general anesthesia and during mechanical ventilation (15,22). In those patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass, significant atelectasis occurs which impairs right ventricular (RV) function. However, lung recruitments using positive pressure have been shown to re-expand collapsed alveoli and improve RV function (23-26). There is a theoretical risk of developing barotrauma leading to pneumomediastinum or pneumothorax during a recruitment; however this is likely less a risk in cardiac surgical patients with relatively healthy lungs (10,27,28).

These cardiopulmonary interactions and hemodynamic concerns limit the willingness of many clinicians to perform positive-pressure recruitment maneuvers in patients with underlying cardiac pathology, making studies involving this population uncommon. One study (29) evaluated the use of a recruitment maneuver performed in twenty pediatric patients with congenital cardiac disease who underwent surgical repair. A single recruitment maneuver was performed shortly after coming off of cardiopulmonary bypass and repeated once in the intensive care unit. Although this study was able to demonstrate an improvement in oxygenation, dynamic lung compliance, arterial to end-tidal CO2 gradient, and end expiratory lung volume, it excluded patients with residual intracardiac lesions following surgery, patients with valvular regurgitation, or respiratory failure defined as FiO2 >0.8. Due to the relatively small number of patients included in this study, as well as their protocol prescribing only two recruitment maneuvers performed per patient, it is difficult to ascertain the overall long-term safety and potential benefits that repeated lung recruitments may provide.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the safety and efficacy of increment-decrement recruitment maneuvers in a larger pediatric patient population following surgery for congenital cardiac disease, hypothesizing that multiple recruitment maneuvers are physiologically beneficial and hemodynamically tolerated in these patients. The safety of these maneuvers was evaluated by examining changes in mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), and central venous pressure (CVP) before, during, and after the recruitment maneuvers. The efficacy of the recruitment maneuvers was determined by changes in oxygenation index (OI) and dynamic lung compliance (Cdyn) following recruitment. To further evaluate the safety of repetitive recruitment we reviewed specific clinical outcomes that included length of mechanical ventilation, length of hospital stay (LOS), mortality and occurrence of pneumothorax and compared to a control group.

Materials and Methods

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Phoenix Children’s Hospital. Subjects who received lung recruitment maneuvers post-operatively, as identified in the electronic medical record, in the Phoenix Children’s Hospital cardiac intensive care unit, a quaternary referral center, from July 2011 through June 2012 following implementation of a lung recruitment protocol, were included in the study. Further inclusion criteria included subjects from 0-18 years of age who were admitted immediately after having open heart surgery with both single- and two-ventricle physiology and who remained on invasive mechanical ventilation. All subjects were mechanically ventilated with Servo-I ventilators (Maquet Critical Care, Solna, Sweden). Subjects with a tracheostomy or who were receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support were excluded from the analysis. A comparison group of consecutive control subjects who did not receive recruitment maneuvers was selected in the following year from July 2012 to June 2013 following an institutional hiatus of the maneuvers during which time quality data was reviewed and the safety of the protocol was assessed. Recruitment maneuvers have subsequently been reinstated and are now standard care in our post-operative cardiac patients on invasive mechanical ventilation.

During the study period, lung recruitment maneuvers were a new standard of care implemented at our institution in the cardiac intensive care unit. They were performed by either the respiratory therapist or attending physician. Most patients had twice daily recruitment maneuvers unless more were clinically indicated based on chest x-ray findings or lung mechanics. The patients may also have fewer recruitment maneuvers if they were hemodynamically unstable, having other procedures, if there was ongoing resuscitation or at the discretion of the attending physician.

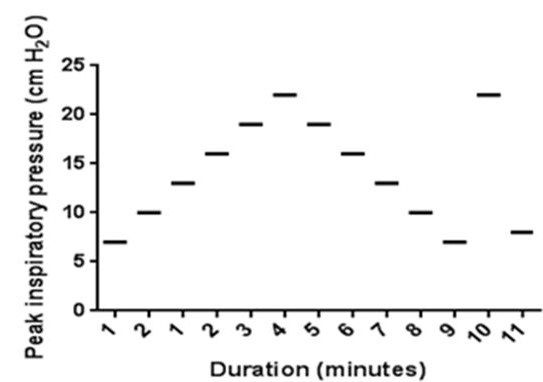

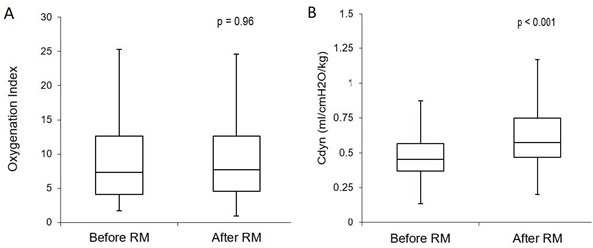

The recruitment maneuver was performed in pressure control mode regardless of the subject’s baseline mode of ventilation. Initial settings were adjusted to achieve a tidal volume of 6mL/kg. PEEP was increased from baseline by 1-2 cmH2O increments while maintaining a fixed inspiratory driving pressure (PIP-PEEP) with each increase sustained for one-minute intervals until either the tidal volume (VT) or dynamic compliance (Cdyn) declined (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Lung recruitment maneuver: recruitment maneuver protocol courtesy of Boriosi et al. (11). Each horizontal bar represents an incremental increase of PEEP by 2 cm H2O in one-minute increments from baseline PEEP.

The recruitment maneuver was terminated if the mean airway pressure surpassed 28 cm H2O. VT and Cdyn were documented with each increase in PEEP. Once the critical opening pressure was identified, PEEP was decreased in a step-wise manner in one-minute 1-2 cmH2O decrements to the critical closing pressure identified by a decrease in VT or Cdyn. Following this point, the PEEP was again increased to the identified critical opening pressure for one minute. It was then brought back down to 2 cmH2O above the critical closing pressure (i.e. “optimal PEEP” level demonstrated by improved compliance and increased tidal volume with less ventilating pressure). The subject was then placed back on their original mode of ventilatory support with the PEEP adjusted to the optimal level, as determined during the recruitment maneuver in order to maintain the newly recruited areas of the lungs open.

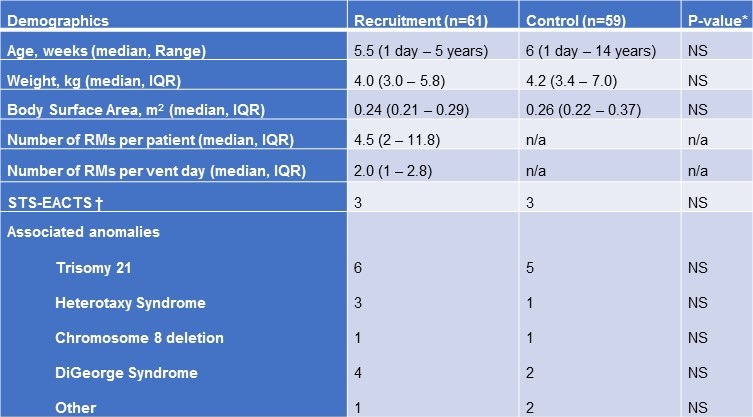

Data Collected: A database was generated with 61 subjects who had lung recruitment maneuvers, and a convenience sample of 59 matched control subjects were selected from our Society for Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database. Demographic data was collected including age, body surface area, associated anomalies or chromosomal abnormalities, cardiac diagnosis, and type of surgical procedure. Clinical outcomes data collected included length of mechanical ventilation, length of hospital stay, mortality, and occurrence of pneumothorax.

Hemodynamic variables including MAP, HR, and CVP were monitored and recorded by the bedside nurse and/or respiratory therapist. For each variable, the two hourly vital sign measurements prior to the start of the maneuver, two measurements during, and the first two hourly measurements following the maneuver were included for analysis. In an attempt to minimize error and to provide a more accurate representation of the subject’s status at the time of interest, the two vital sign measurements in each category were averaged as physiologic variables are dynamic. The respiratory physiologic variables monitored were dynamic compliance and oxygenation index. In order to further investigate the clinical effects of potentially decreased cardiac output, we reviewed the changes in inotropic and vasopressor support before, during, and after the performance of each recruitment maneuver.

Statistical Analysis: Subject demographic and clinical characteristics between the control and recruitment maneuver groups were reported as medians, interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables and frequencies, percentages for categorical variables. The Wilcoxon Rank Sum was used to compare the continuous variables; while Chi-squared/Fisher’s Exact Tests were used to compare the categorical variables. The Linear Mixed Model was used to ascertain trends in hemodynamic outcomes (mean arterial pressure, heart rate, and central venous pressure) across three timepoints (before, during and after the recruitment maneuver). If the overall trend showed statistical significance, the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was used to ascertain differences via multiple comparisons followed by the Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. Before and after differences in physiological outcomes (oxygenation index and dynamic compliance) were assessed using the Wilcoxon Signed Rank. All p-values were 2-sided and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data analyses were conducted using STATA version 14 (STATACorp; College Station, TX).

Results

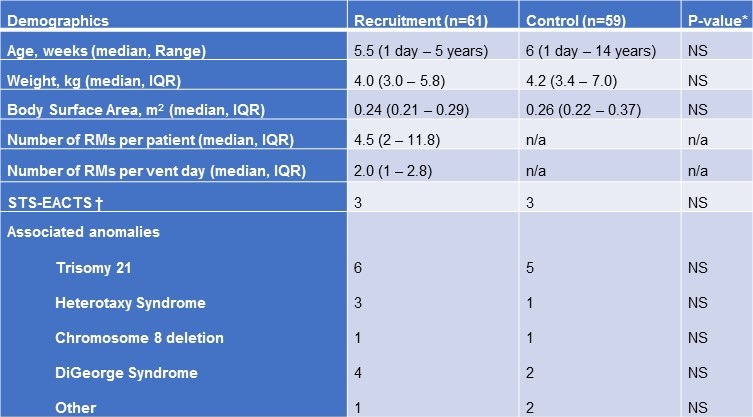

A total of 61 subjects underwent lung recruitment from June 2011 to June 2012 (Table 1) accounting for a total of 439 recruitment maneuvers during this time.

Table 1. Comparison of subjects receiving recruitment maneuvers versus controls.

Recruitment was initiated in the post-operative period once deemed safe by the primary intensivist. The maneuvers were performed as frequently as every two hours but, on average, subjects in the cohort received 2 recruitment maneuvers per ventilator day. Both groups had similar congenital heart disease diagnoses with an average Society of Thoracic Surgeons-European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery Congenital Heart Surgery Mortality Score of 3 in each group covering a variety of anatomical defects and surgical procedures performed. Subjects with residual intracardiac lesions on intraoperative transesophageal echocardiogram were included in the study.

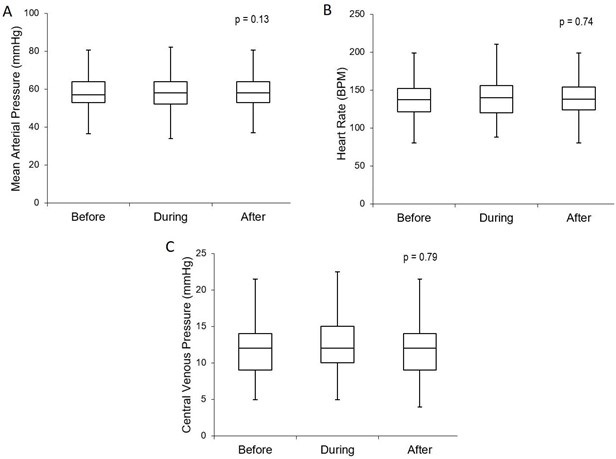

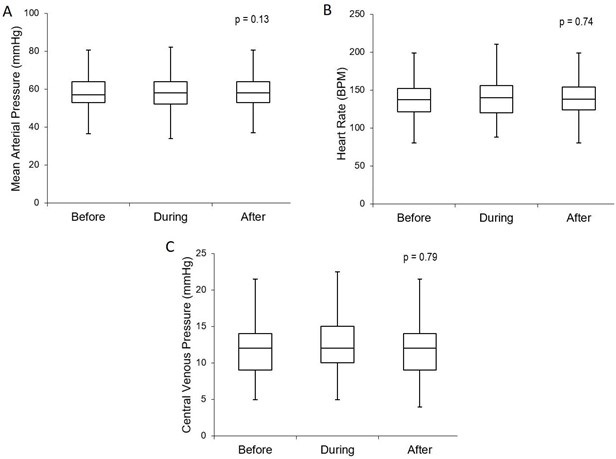

Hemodynamics: All 61 subjects tolerated the maneuvers with no hemodynamic instability defined as hypotension, need for fluid bolus during the recruitment, bradycardia, or dysrhythmias. No subject had any of the maneuvers discontinued prematurely. We found no significant difference in the MAP (p = 0.13, 95% CI) (Figure 2a) or HR (p = 0.74, 95% CI) (Figure 2b) during the time intervals measured.

Figure 2. Hemodynamics: comparison of hemodynamic measurements before, during, and after the recruitment maneuvers. There was no significant change in MAP (Fig 2a), HR (2b), or CVP (2c) during or after the maneuvers. Boxplot with whiskers with minimum/maximum 1.5 IQR.

Due to the transient increase in intrathoracic pressure that theoretically results in a decrease in venous return and therefore cardiac output, CVP was monitored throughout the recruitments. The CVP measurement did not show a significant change with the recruitment maneuver (p = 0.79, 95% CI) (Figure 2c).

In order to further investigate the clinical effects of potentially decreased cardiac output, we reviewed the changes in inotropic and vasopressor support surrounding the performance of the recruitment maneuvers. All infusion rates of epinephrine, norepinephrine, vasopressin, dopamine, milrinone, and calcium were documented prior to, during, and after lung recruitments. Of the 439 recruitment maneuvers performed, 84% were performed without any change in inotropic support during or within 1 hour after completion of the maneuver. Inotropic support was decreased after the recruitment in 12% of maneuvers. Only 3% of maneuvers required an increase in support. No subjects had any significant hypotension requiring fluid bolus administration during or immediately after the maneuvers.

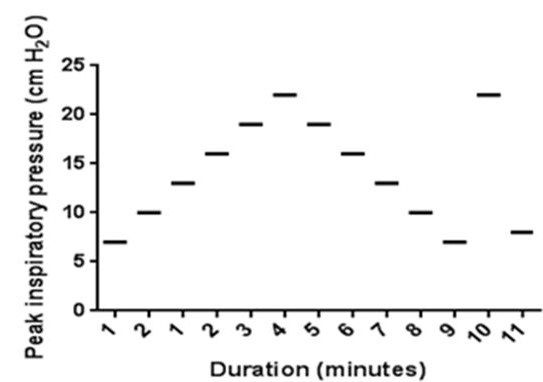

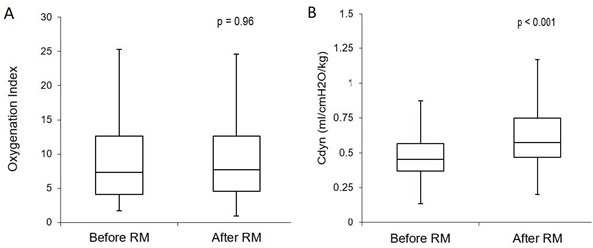

Efficacy: The efficacy of recruitment maneuvers on lung function was determined by measuring changes in the OI and Cdyn before and after recruitment. There was no statistically or clinically significant change in the OI with a median OI before recruitment of 7.3 (IQR 4.1-12.6) and after 7.7 (IQR 4.6-12.6) (p = 0.96, 95% CI) (Figure 3a).

Figure 3. Efficacy: comparison of physiologic measures used to assess efficacy of the recruitment maneuvers. No significant change was demonstrated in the OI before and after recruitment (3a). There was a significant increase in Cdyn by an average of 28% immediately after the maneuvers (3b). Boxplot with whiskers with minimum/maximum 1.5 IQR.

Of the 439 maneuvers, 83% resulted in a measurable improvement of the Cdyn with all 61 of the subjects demonstrating an increase at least once over the course of the interventions. The Cdyn increased from 0.45 ml/cmH2O/kg (IQR 0.37-0.57) to 0.58 ml/cmH2O/kg (IQR 0.47-0.75) afterwards (p < 0.001, 95% CI). (Figure 3b). The duration of improved Cdyn was an average of 8 hours +/- 11.4 hours. Subjects continued to show improvement with repeated efforts.

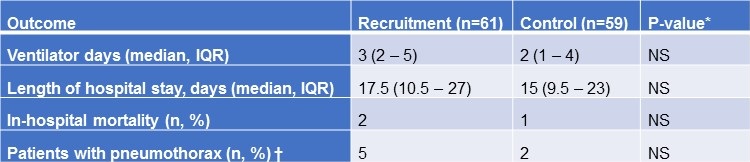

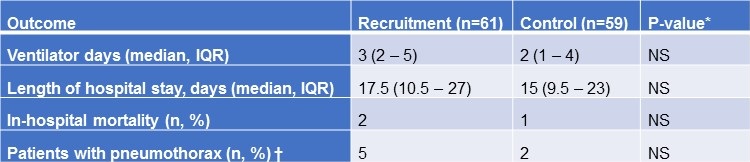

Clinical Outcomes. All subjects included in this study were on invasive mechanical ventilation support on return from cardiac surgery for a minimum of 24 hours. As shown in Table 2, there was no significant difference in the number of ventilator days between the recruitment maneuver and control groups (p = 0.26, 95% CI).

Table 2. Clinical outcomes.

There was also no difference in the occurrence of extubation failure requiring reintubation between both groups (p = 0.52). There was no difference in hospital LOS with the RM group staying 17.5 days (10.5 – 27) and control group 15 days (9.5 – 23) (p = 0.28, 95% CI) or in the rate of in-hospital mortality (p = 0.58, 95% CI). Despite the theoretical concern for development of pneumothorax with recruitment maneuvers, there was no significant difference in the occurrence between the two groups (p = 0.26, 95% CI).

Discussion

Our results suggest that lung recruitment maneuvers are well tolerated in the pediatric post-operative cardiac patient population both with and without residual intracardiac shunts, and may be repeated for the duration of their time requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Despite being at high risk of hemodynamic instability shortly after surgery, especially following complex repair and prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass time, our subjects did not require significant preload optimization or escalation of inotropic support during the maneuvers. We were also able to demonstrate that there was an improvement in dynamic lung compliance following the maneuver. Not only were these maneuvers tolerated from a hemodynamic standpoint, but there were no adverse outcomes when compared to control subjects with no difference in the length of mechanical ventilation, LOS, mortality, or the occurrence of pneumothorax.

Advocacy for the optimization of oxygenation and ventilation through the use of an “open lung” strategy, especially in the treatment of ARDS, has been present in the critical care literature for decades. Multiple reports have described the importance of lung recruitment with high inspiratory pressures in addition to the appropriate PEEP above closing pressures to maintain optimal gas exchange and minimize hypercapnia (30). Recruitment maneuvers are recommended in the protective ventilation strategy in adult post-operative patients who have undergone cardiac surgery with significant benefits as compared to traditional ventilation (31,32). To our knowledge, there is very limited data on the use of lung recruitment maneuvers in the pediatric cardiac patient population with the majority of the pediatric literature focusing on the use of these maneuvers in patients with ARDS. Scohy et al. (29) previously evaluated the use of recruitment maneuvers in subjects undergoing surgery for congenital cardiac disease but excluded several key subgroups of these subjects and did not evaluate the continued use of recruitment maneuvers over the entire course of mechanical ventilation. Amorim et al. (6) assessed the tolerance of recruitment maneuvers in a small population of infants who were prone to pulmonary arterial hypertension and excessive pulmonary circulation just after skin closure for open heart surgery. In general, data on the safety of these maneuvers in pediatric patients is very limited.

The efficacy of lung recruitment maneuvers in patients with ARDS remains controversial with some studies suggesting an improvement in oxygenation and dynamic or static compliance (1,11,20,21,33-35), some demonstrating brief or no improvement (36,37), and others that show improvement but suggest that the deleterious hemodynamic effects may outweigh the benefits (14). In children with ARDS, a staircase recruitment strategy has been described to improve oxygenation with increasing PaO2. In order to sustain improved oxygenation, the PEEP must be set above the critical closing pressure of the lung following recruitment (11,21,38,39). Boriosi et al. (11) further described that a “re-recruitment” maneuver that was performed at critical opening pressures for a short period of time improved the PaO2/FiO2 ratio for up to 12 hours and OI for up to four hours following the recruitment maneuver. In our study, we were not able to demonstrate an improvement in the OI. However, we did demonstrate a significant improvement in Cdyn of 29% following completion of each recruitment which was sustained for eight hours. The lack of improvement in oxygenation may be secondary to less primary lung injury in our patient population, or due to the common presence of residual intracardiac shunts. The increase in Cdyn may be a clinically significant change for some patients and could help reduce the time on invasive mechanical ventilation.

The overall goal of recruitment maneuvers is to open atelectatic alveoli, increase end expiratory lung volume, and improve gas exchange. However, as discussed, generation of high intrathoracic pressures during the maneuvers can theoretically result in hemodynamic instability (4,10,14,20,21). Currently, there is no specific non-invasive monitoring that is the best indicator for hemodynamic assessment during recruitment maneuvers, with vital sign changes serving as a surrogate marker for the safety of the recruitment maneuver (40). In our study, there was no change in MAP, HR, or CVP from baseline, during, or after the maneuvers indicating that they were well tolerated from a hemodynamic standpoint with 97% of the recruitment maneuvers using the same or less inotropic support and no subject required fluid bolus administration for hypotension during any of the maneuvers.

The occurrence of barotrauma, including pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax, has been reported with the intermittent increase in peak airway inspiratory pressures (10,27,28). In our study, there was no significant difference in the occurrence of pneumothorax between the two groups. With the preponderance of studies on recruitment maneuvers being performed in the adult ARDS patient population, there is limited data on pediatric outcomes in mortality and duration of mechanical ventilation. A Cochrane review performed by Hodgson et al. (41) demonstrated no reduction in mortality or length of mechanical ventilation following recruitment maneuvers in adult ARDS patients. In our study, we demonstrated similar findings in that there was no difference in mortality, length of mechanical ventilation, or LOS in pediatric post-operative congenital cardiac patients with or without the maneuvers.

There were several limitations to our study. This was a single-center, retrospective study that involved a small pediatric cardiac population. Our assessment of cardiac output was dependent on measurements of MAP and CVP. We also did not investigate the occurrence of hypercapnia during the recruitment maneuvers. Overdistension of open alveoli can occur resulting in an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance and a decrease in blood flow to the alveoli, thereby increasing dead space ventilation (21). There are a number of studies demonstrating that throughout recruitment maneuvers there is an increase in PaCO2, with a potential need to titrate the respiratory rate on the ventilator in order to maintain constant minute ventilation throughout the maneuver, as this development of hypercapnia during the maneuvers may result in adverse effects (11,34,36,41). A multifaceted approach to monitoring the effectiveness as well as any negative consequences of these maneuvers including end-expiratory lung volumes, dead space ventilation, pulmonary compliance, volumetric capnography as well as bedside ultrasound would be beneficial (40). This study was conducted prior to our institution utilizing volumetric CO2 analysis to monitor physiologic gas exchange as well as dead-space ventilation during mechanical ventilation.

Conclusion

Overall, our study demonstrated that pediatric post-operative cardiac subjects, having a wide variety of cardiopulmonary physiology, tolerated repeated recruitment maneuvers without significant hemodynamic changes or adverse outcomes. As has been the case in many previous studies, we did not find any significant improvement in oxygenation, length of mechanical ventilation, or length of stay. However, as recruitment maneuvers have been shown to be an integral part of lung protection strategies and to benefit adults following open heart surgery, it is possible that our pediatric post-operative cardiac patients could benefit from the integration of recruitment maneuvers into ventilator management strategies while on invasive mechanical ventilation. Future prospective studies need to be conducted to further evaluate the potential benefit and utility of lung recruitment maneuvers in pediatric patients without significant lung disease.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff of the Pediatric Cardiovascular Intensive Care Unit at Phoenix Children’s Hospital for their assistance and support in this study. We would also like to acknowledge the work of Juan P Boriosi, MD and his colleagues for use of their recruitment protocol and RM diagram (Figure 1) in our study.

Contributions: Renee L. Devor MD1,4,5,6, Harjot K. Bassi, MD1-6, Paul Kang MPH4, Tiffany Morandi MD1-3, Kristi Richardson RT2,3, John J. Nigro MD2, Christine Tenaglia RT2,3, Chasity Wellnitz RN, BSN, MPH2,4, and Brigham C. Willis MD3,6

1Literature search, 2Data collection, 3Study Design, 4Analysis of data, 5Manuscript preparation, 6Review of manuscript

References

- Amato MB, Barbas CS, Medeiros DM, Magaldi RB, Schettino GP, Lorenzi-Filho G, et al. Effect of a protective-ventilation strategy on mortality in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 1998;338(6):347-54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marini JJ. Ventilation of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Looking for Mr. Goodmode. Anesthesiology 1994;80(5):972-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreyfuss D, Saumon G. Ventilator-induced lung injury: lessons from experimental studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157(1):294-323. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay LN, Slutsky AS. Ventilator-induced lung injury: from the bench to the bedside. Intensive Care Med 2006;32(1):24-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelosi P, Goldner M, McKibben A, Adams A, Eccher G, Caironi P, et al. Recruitment and derecruitment during acute respiratory failure: an experimental study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164(1):122-30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim Ede F, Guimaraes VA, Carmona F, Carlotti AP, Manso PH, Ferreira CA, et al. Alveolar recruitment manoeuvre is safe in children prone to pulmonary hypertensive crises following open heart surgery: a pilot study. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2014;18(5):602-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres A, Gatell JM, Aznar E, el-Ebiary M, Puig de la Bellacasa J, Gonzalez J, et al. Re-intubation increases the risk of nosocomial pneumonia in patients needing mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;152(1):137-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer JE, Allen P, Fanconi S. Delay of extubation in neonates and children after cardiac surgery: impact of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med 2000;26(7):942-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscedere JG, Mullen JB, Gan K, Slutsky AS. Tidal ventilation at low airway pressures can augment lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;149(5):1327-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapinsky SE, Mehta S. Bench-to-bedside review: Recruitment and recruiting maneuvers. Crit Care 2005;9(1):60-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boriosi JP, Sapru A, Hanson JH, Asselin J, Gildengorin G, Newman V, et al. Efficacy and safety of lung recruitment in pediatric patients with acute lung injury. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2011;12(4):431-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelosi P, Gama de Abreu M, Rocco PR. New and conventional strategies for lung recruitment in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care 2010;14(2):210. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gattinoni L, Caironi P, Cressoni M, Chiumello D, Ranieri VM, Quintel M, et al. Lung recruitment in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2006;354(17):1775-86. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das A, Haque M, Chikhani M, Cole O, Wang W, Hardman JG, et al. Hemodynamic effects of lung recruitment maneuvers in acute respiratory distress syndrome. BMC Pulm Med 2017;17(1):34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendixen HH, Hedley-Whyte J, Laver MB. Impaired oxygenation in surgical patients during general anesthesia with controlled ventilation. a concept of atelectasis. N Engl J Med 1963;269:991-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brismar B, Hedenstierna G, Lundquist H, Strandberg A, Svensson L, Tokics L. Pulmonary densities during anesthesia with muscular relaxation--a proposal of atelectasis. Anesthesiology 1985;62(4):422-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedenstierna G, Strandberg A, Brismar B, Lundquist H, Svensson L, Tokics L. Functional residual capacity, thoracoabdominal dimensions, and central blood volume during general anesthesia with muscle paralysis and mechanical ventilation. Anesthesiology 1985;62(3):247-54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedenstierna G, Tokics L, Strandberg A, Lundquist H, Brismar B. Correlation of gas exchange impairment to development of atelectasis during anaesthesia and muscle paralysis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1986;30(2):183-91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luecke T, Pelosi P. Clinical review: Positive end-expiratory pressure and cardiac output. Crit Care 2005;9(6):607-21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth I, Leiner T, Mikor A, Szakmany T, Bogar L, Molnar Z. Hemodynamic and respiratory changes during lung recruitment and descending optimal positive end-expiratory pressure titration in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2007;35(3):787-93. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim CM, Jung H, Koh Y, Lee JS, Shim TS, Lee SD, et al. Effect of alveolar recruitment maneuver in early acute respiratory distress syndrome according to antiderecruitment strategy, etiological category of diffuse lung injury, and body position of the patient. Crit Care Med 2003;31(2):411-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedenstierna G, Edmark L. Mechanisms of atelectasis in the perioperative period. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2010;24(2):157-69. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo S, Siri J, Acosta C, Palencia A, Echegaray A, Chiotti I, et al. Lung recruitment improves right ventricular performance after cardiopulmonary bypass: A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2017;34(2):66-74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tusman G, Bohm SH, Tempra A, Melkun F, Garcia E, Turchetto E, et al. Effects of recruitment maneuver on atelectasis in anesthetized children. Anesthesiology 2003;98(1):14-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tusman G, Bohm SH. Prevention and reversal of lung collapse during the intra-operative period. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2010;24(2):183-97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothen HU, Neumann P, Berglund JE, Valtysson J, Magnusson A, Hedenstierna G. Dynamics of re-expansion of atelectasis during general anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 1999;82(4):551-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Pizarro P, Garcia-Fernandez J, Canfran S, Gilsanz F. Neonatal pneumothorax pressures surpass higher threshold in lung recruitment maneuvers: an in vivo interventional study. Respir Care 2016;61(2):142-148. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan E, Checkley W, Stewart TE, Muscedere J, Lesur O, Granton JT, et al. Complications from recruitment maneuvers in patients with acute lung injury: secondary analysis from the lung open ventilation study. Respir Care 2012;57(11):1842-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scohy TV, Bikker IG, Hofland J, de Jong PL, Bogers AJ, Gommers D. Alveolar recruitment strategy and PEEP improve oxygenation, dynamic compliance of respiratory system and end-expiratory lung volume in pediatric patients undergoing cardiac surgery for congenital heart disease. Paediatr Anaesth 2009;19(12):1207-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhm SH, Vazquez de Anda GF, Lachmann B. The Open Lung Concept. In: Yearbook of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine 1998, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1998. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Lellouche F, Delorme M, Bussieres J, Ouattara A. Perioperative ventilatory strategies in cardiac surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2015;29(3):381-95. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis Miranda D, Gommers D, Struijs A, Dekker R, Mekel J, Feelders R, et al. Ventilation according to the open lung concept attenuates pulmonary inflammatory response in cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2005;28(6):889-95. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasso S, Mascia L, Del Turco M, Malacarne P, Giunta F, Brochard L, et al. Effects of recruiting maneuvers in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome ventilated with protective ventilatory strategy. Anesthesiology 2002;96(4):795-802. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges JB, Okamoto VN, Matos GF, Caramez MP, Arantes PR, Barros F, et al. Reversibility of lung collapse and hypoxemia in early acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174(3):268-78. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badet M, Bayle F, Richard JC, Guerin C. Comparison of optimal positive end-expiratory pressure and recruitment maneuvers during lung-protective mechanical ventilation in patients with acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Respir Care 2009;54(7):847-54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villagra A, Ochagavia A, Vatua S, Murias G, Del Mar Fernandez M, Lopez Aguilar J, et al. Recruitment maneuvers during lung protective ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165(2):165-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brower RG, Morris A, MacIntyre N, Matthay MA, Hayden D, Thompson T, et al. Effects of recruitment maneuvers in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome ventilated with high positive end-expiratory pressure. Crit Care Med 2003;31(11):2592-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheir JN, Walsh BK, Smallwood CD, Rettig JS, Thompson JE, Gomez-Laberge C, et al. Comparison of 2 lung recruitment strategies in children with acute lung injury. Respir Care 2013;58(8):1280-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruces P, Donoso A, Valenzuela J, Diaz F. Respiratory and hemodynamic effects of a stepwise lung recruitment maneuver in pediatric ARDS: a feasibility study. Pediatr Pulmonol 2013;48(11):1135-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godet T, Constantin JM, Jaber S, Futier E. How to monitor a recruitment maneuver at the bedside. Curr Opin Crit Care 2015;21(3):253-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson C, Keating JL, Holland AE, Davies AR, Smirneos L, Bradley SJ, et al. Recruitment manoeuvres for adults with acute lung injury receiving mechanical ventilation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009(2):Cd006667. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Devor RL, Bassi HK, Kang P, Morandi T, Richardson K, Nigro JJ, Tenaglia C, Wellnitz C, Willis BC. Safety and efficacy of lung recruitment maneuvers in pediatric post-operative cardiac patients. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2020;20(1):16-28. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc068-19 PDF

Thursday, March 26, 2020 at 2:27PM

Thursday, March 26, 2020 at 2:27PM