Stella C. Pak, MD1

Edinen Asuka, MD2

1Department of Medicine,

Orange Regional Medical Center

Middletown, NY USA

2All Saints University School of Medicine

Dominica

Abstract

In spite of the continuing efforts of researchers and practitioners, the mortality rate for acute type A aortic dissection remains relatively high at about 20-50%. Conventional risk factors associated with acute type A aortic dissection include a family history or prior history of aortic disease, connective tissue disease, smoking, alcohol use, substance abuse, diabetes mellitus type II, and age of 40 or greater. With the growing awareness for fitness in our society, vigorous exercise is emerging as a novel risk factor for acute type A Aortic dissection. Herein, we present a non-trauma related acute type A aortic dissection secondary to weight-lifting in a young man. We also reviewed several articles in order to provide a comprehensive literature overview for readers, clinicians and future researchers.

Case Report

A 45-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented to the Emergency Department after having a “popping” sensation in his chest while weight-lifting with an 80-lbs (36.3 kg) dumbbell at a gym. He is an avid weight-lifter. This chest discomfort was immediately followed by a sensation of electric shock from his chest down to his legs and a transient loss of bilateral vision. He then developed an acute episode of lightheadedness, diaphoresis, throbbing headache, and a heavy-pressure in his neck, chest, and back. He denied any recent trauma or injury. He denied the use of tobacco, recreational drugs, or anabolic steroid. He denied the history of connective tissue diseases or cardiovascular diseases.

He was hypotensive with blood pressure of 99/45 mmHg. However other vital signs were within the normal limit: a temperature of 98.2 °F, a heart rate of 74/min, and a respiration rate of 15/min, an oxygen saturation of 97% at room air. His physical examination was remarkable for diminished pulses on his right upper and lower extremities. He did not have any marfanoid traits, such as tall stature, elongated face, or dolichostenomelia. His height and weight measured at the time of admission were 181cm and 95.7kg respectively (BMI 29.2).

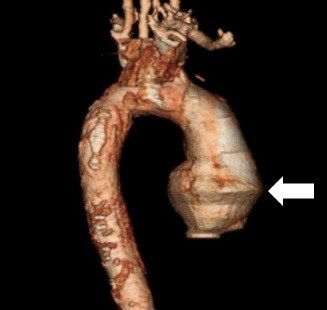

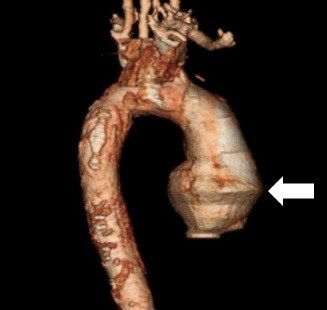

His white blood count was elevated at 12.1 x 109/L, but his hemoglobin remained stable at 15.6 g/dL. His troponin I was 0.26. He was found to have acute renal injury with BUN of 26 and creatinine of 1.7. His ECG, Chest X-ray, and CT of head and neck were unremarkable. He subsequently underwent a diagnostic cardiac catheterization, which revealed a swirling pattern and delayed washout of the contrast, findings suggestive of a false lumen. CT angiography displayed type A aortic dissection from the aortic root all the way down to the abdomen (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CT angiography demonstrating ascending aortic dissection (arrow). The area with the arrow is the ascending portion of the aorta.

TEE visualized a rupture in the left coronary cusp at the aortic valve was visualized with the ejection fraction of 40% to 45%. Histopathological examination of the aortic wall and the aortic valve cusps revealed myxoid degeneration. There was no evidence of cystic medial necrosis.

He underwent an emergent repair of aorta with aortic root replacement, using a Dacron aortic graft and a mechanical aortic valve (25-On-X). Heparin bridging was initiated once his post surgically bleeding risk was low. Warfarin was later started with therapeutic INR goal of 2.0 to 3.0. On postoperative day 10, he was discharged on Aspirin 81 mg, warfarin and metoprolol 50 mg daily.

At 1 month post-discharge follow-up, his distal pulse was strong and equal in all four extremities. He was asymptomatic with no complaints of chest pain, dyspnea, headache, or lightheadedness.

Literature Review

Aortic dissection occurs when the tunica intima of the aorta develops a tear that extends into the inner two-third layer of its tunica media which consists of collagen, smooth muscle and elastic fibers. The above pathological changes lead to the formation of a true lumen and a false lumen separated by an intimal flab (1-14). This causes blood to escape into the false lumen and incite a cascade of events. The external elastic lamina separates the tunica media from the adventitial layer, which serves as an external scaffolding. The tunica adventitia consists of fibroblast cells, collagen and elastic fibers. On the other hand, the tunica intima is made of endothelial cells on basement membrane; separated from the tunica media by the internal elastic lamina (2-14). As blood enters the false lumen, retrograde or anterograde propagation of blood occurs due to pressure changes. If a retrograde propagation takes place within the false lumen, it can extend into the aortic root through the sinotubular junction, eventually causing damage to the aortic root and its content or escape into the pericardial space; consequently leading to aortic insufficiency, acute coronary syndrome or cardiac tamponade (10-34). The contents of the aortic root in question include sinuses of Valsalva where the coronary sinuses and the orifices of the coronary arteries are located, or other structures such as aortic annulus, commissures, leaflets (cusps) and ventriculo-aortic junction. In the case of an anterograde propagation, the blood collection within the false lumen can extend distally from the site of initial tear to the branches of the aorta such as brachiocephalic trunk (innominate artery), left subclavian artery, renal arteries and mesenteric arteries thereby leading to stroke, limb ischemia, renal insufficiency and bowel ischemia. Involvement of the brachiocephalic trunk or the left subclavian artery can also cause pseudohypotension (35-41). In some cases, distal extension can reach the site of aortic bifurcation and recanalize into the intravascular compartment; thereby, creating a double barrel aorta. This in effect, reduces the risk of aortic rupture (10,34-44). In a clinical scenario where there is no preceding intimal tear, the most likely causes are always connective tissue diseases such as Marfan syndrome (FBN1 gene mutation), Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (vascular type-COL3A1 gene mutation), familial thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection (TGFBR1 and TGFBR2, FBN1, MYH11, and ACTA 2 genetic mutations), and Leoys-Dietz aneurysm syndrome (TGFBR1 or TFGBR2 gene mutations) (12,14,34-44). In such cases, there is an initial formation of intramural hematoma, which may occur secondary to rupture of the aortic vasa vasorum. Disruption of the vaso vasorum can also occur due inflammatory response generated from vasculitides or infectious causes like syphilis.

Aortic dissection is relatively rare when compared to other cardiovascular diseases such as ruptured aortic aneurysm, acute coronary syndrome and abdominal aortic aneurysm. The true incidence of aortic dissection is hard to determine because most case approximations are made from autopsy reports (34,39,40-45). Although, the estimated incidence is 5 to 30 cases per million people yearly. Aortic dissections are known to occur more in males compared to females with men constituting about 65% of cases. Peak age of onset is between 50-65 years. In a population-based study of all Olmsted County, Minnesota, residents with aortic dissection between 1995 to 2015, it was noted that age- and sex-adjusted incidence of aortic dissection for men was 10.2 per 100,000 person-years versus 5.7 per 100,000 person-years for women (1,11-14,46). Aortic dissection is commonly classified based on time of presentation and structural variations. With regards to time of presentation, it can be acute (less than 2 weeks) or chronic (greater than 2 weeks) (1,46). Chronic aortic dissections tend to have better prognosis.

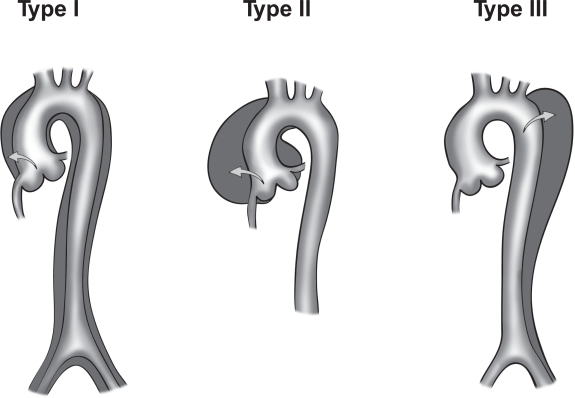

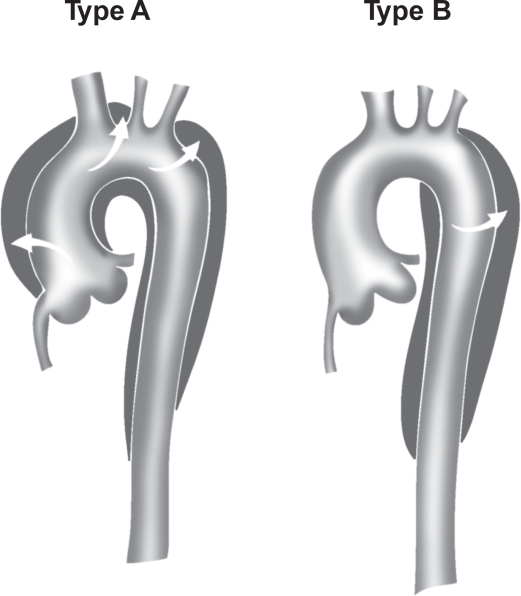

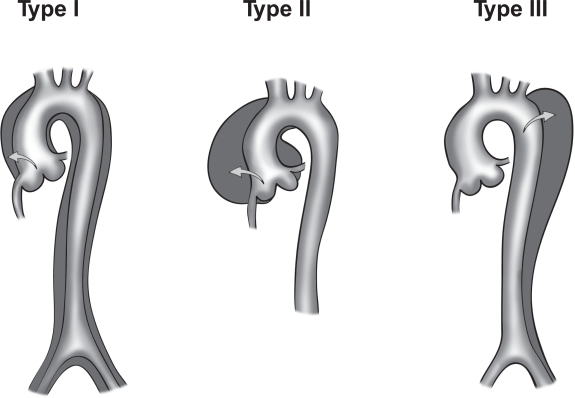

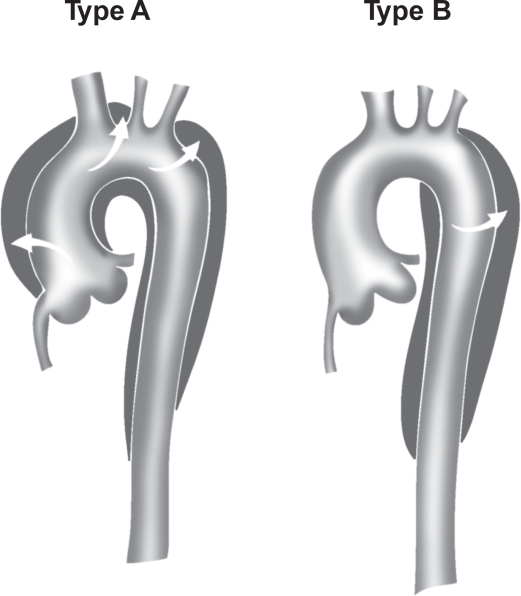

There are two main anatomic classifications, DeBakey (Figure 2) and Stanford (Figure 3). Most aortic dissections originate mainly from the ascending aorta with the rest emanating from the aortic arch and the descending aorta (1,46).

The DeBakey classification is divided into three main types:

- Type I- emerges from the ascending aorta, extends to the aortic arch and often involving the distal segment of the aorta. Most common in the younger population (less than 40 years). It is also the most serious form of aortic dissection.

- Type II- Emerges from the ascending aorta and is restricted to this section of the aorta.

- Type III- Emerges from the descending aorta extending distally above the diaphragm (Type IIIa) or beyond the diaphragm into the abdominal aorta (Type IIIb) (34,46).

Figure 2. Illustrations of DeBakey classification (Type I, II, and III). T Paul Tran and Ali Khoynezhad. Dove Medical Press Limited. 2009. Available at: https://www.dovepress.com/articles.php?article_id=2444 (accessed 8/7/20).

The Stanford classification is broken down into:

- Type A- Involvement of the ascending aorta irrespective of the origin of intimal tear. A composite of DeBakey Type I and II.

- Type B- Involvement of the descending aorta (distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery) and its distal component. An analogy of type III DeBakey (1,34,46).

Figure 3. Stanford classification of aortic dissection (Type A and B). T Paul Tran and Ali Khoynezhad. Dove Medical Press Limited. 2009. Available at: https://www.dovepress.com/articles.php?article_id=2444 (accessed 8/7/20).

Etiology. There are several risk factors for aortic dissection. The main predisposing risk factors most commonly reported include:

- Hypertension (Associated with about 70%-80% of cases).

- Connective tissue diseases and genetic disorders such as Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Familial thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection, Leoys-Dietz aneurysm syndrome, Turner syndrome, and bicuspid aortic valve (5% likelihood of aortic dissection).

- Age greater than 40 years (75% of cases occur in patients between 40-70 years)

- Use of illicit substances such as cocaine, and ecstasy.

- Pre-existing aortic aneurysm

- Previous history of aortic dissection

- Family history of aortic dissection

- Pregnancy

- Vasculitides and autoimmune diseases such as Giant cell arteritis, Takayasu’s arteritis, polyarteritis nodosa, and Behcet’s disease.

- Iatrogenic causes such as cardiac catheterization, aortic valve replacement, coronary artery bypass graft and intra-aortic balloon pump.

- Tertiary syphilis

- Use of anabolic steroids

- Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer secondary to infiltration of the tunica media by an atherosclerotic plaque. Meaning, risk factors for atherosclerosis such as smoking, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes are implicated in aortic dissection.

- Penetrating chest trauma

- Chronic alcohol use

- Weight-lifting is a novel risk factor for aortic dissection even in individuals without connective tissue diseases or cardiovascular risk factors. The existence of other risk factors only makes it more likely to occur (17-20, 40-46).

Signs and Symptoms: The diagnosis of aortic dissection is greatly missed by most physicians in the emergency department upon presentation. Delay in treatment can lead to an increase in mortality to about 50% within the first 48 hours. It is highly crucial the diagnosis is made quickly and treatment is initiated promptly to decrease the risk of mortality (1,41-46). With respect to clinical presentation, patients present with following symptoms:

- Severe tearing chest pain of sudden onset. Pain may be located in the anterior chest wall, interscapular region and in the abdomen. Anterior chest wall pain is often due to involvement of the ascending aorta while interscapular back pain and abdominal pain are associated with involvement of the distal segments of the aorta due to anterograde extension of the false lumen. Note that about 10% of patients present with painless aortic dissection; which is more common in patients with connective tissue diseases such as Marfan syndrome. Some patients present with pleuritic chest pain secondary to pericardial involvement. Overall, chest pain is the most common symptom; occurring in about 80-96% of patients, with anterior chest pain being the most reported. About 71.4% of painless aortic dissection present with a normal ECG reading. Coronary malperfusion may result in cardiac arrest (1,14,26-46).

- Sweating, nausea and vomiting (may occur due to autonomic changes)

- Headache

- Lightheadedness

- Back pain

- Abdominal pain

- Neck or jaw pain (aortic arch involvement)

- Neurologic deficits (hemiparesis, hemiplegia hemianesthesis and loss of vision) and syncope as a result of hypovolemia, arrhythmia, acute coronary syndrome, increase vagal tone or involvement of the innominate artery and its branches (such as the internal carotid artery) (1,40-46).

- Horner syndrome (Ptosis, miosis and anhidrosis) secondary to obstruction of sympathetic outflow tract.

- Hoarseness due to vagus nerve compression.

- Exertional leg and gluteal pain may occur if the iliac artery is involved.

- Paresthesia, and extremity pain may occur due to limb ischemia.

- Dyspnea

- Dysphagia

- Hemoptysis

- Anxiety and palpitations

Common signs observed in patients with aortic dissection include:

- Differential blood pressure measurements in the upper extremities

- High blood pressure (More common in Type B aortic dissection)

- Hypotension (More common in Type A aortic dissection)

- Wide pulse pressure measurement (signifying aortic valve involvement)

- Diastolic murmur (secondary to aortic insufficiency)

- Muffled heart sounds

- Weak peripheral pulses

- ECG changes indicating acute coronary syndrome

- Decreased breath sounds, dullness to percussion if pleural effusion is present. Pleural effusion may be as result of inflammatory response, aneurysm leakage or eventual rupture of the dissected aorta.

- Horner syndrome

- Changes in mental status

Patients may experience a wide range of complications if they are not managed early. Some of which include stroke, paraplegia, life threatening arrhythmia with cardiac arrest, paraplegia, limb amputation, multiple organ failure, severe cardiac tamponade, renal failure, bowel ischemia, myocardial infarction, aortic regurgitation, superior vena cava syndrome and even death (1,22,14,46).

Diagnostic modalities and findings.

- ECG and cardiac enzyme (troponin) level must be checked to exclude myocardial involvement. ECG findings are usually non-specific with nearly 1-2% showing ST-elevation (1,39,41-46).

- Baseline blood work such as CBC, electrolytes, Blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine level must be established. D-dimer may be used it low risk patients to exclude diagnosis. Although, due to lack of evidence to validate its use, it is not strongly recommended (40,46).

- Chest x-ray- findings on may include widened mediastinum (present in greater than 80%), calcium sign, apical cap (left); loss of paratracheal stripe; involution of mainstem bronchus; pleural effusion, tracheal and esophageal deviation. Normal x-ray findings occur in about 20% cases (1,41,46).

- Computed Tomography (CT)-chest and abdomen with iodinated contrast- fast, noninvasive and available in most emergency departments. It is used to detect the region of tear and aids surgical planning. Not recommended for patients with contrast allergy, older patients (greater than 65 years), poor renal function and history of renal insufficiency.

- Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE): It is relatively available, noninvasive and best for ascending aortic dissections to detect changes or damages structures within the aortic root. It can be done at bedside and does not require contrast media. Although, it is operator dependent and discouraged in patients with esophageal varices, masses or strictures (14,39,46).

- Magnetic resonance Imaging (MRI): It is used for detection of site of tear, assessment of dissection and involvement of branches of aorta, ascertain the presence and degree of aortic insufficiency. Iodinated contrast is not needed. It also aids surgical planning but it is time consuming, expensive, not readily available in some hospitals and not advisable for use in patients with metallic implants such as pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

- Doppler ultrasound: This can be useful in patients presenting with signs of limb hypoperfusion to assess for diminished blood flow on the extremities involved (22,46).

Management: Aortic dissection can be managed surgically or conservatively with medications. Type A aortic dissections often require surgical management while type B aortic dissection can be managed conservatively with medications. Medical management is necessary at presentation to help stabilize patient’s vitals. The mean arterial blood pressure goal is often between 60 to 75mm Hg (1,14,23,46). Medical management is started by administration of intravenous short and fast acting beta-blockers (esmolol, propanolol and labetalol) and morphine for pain management (14,23,46). Sodium nitroprusside is then given to the patient to enhance vasodilation and ensure adequate visceral perfusion. Patients with contraindications to beta-clockers (2nd or 3rd degree heart block, decompensated heart failure, severe asthma, and sinus bradycardia) should be given non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (verapamil and diltiazem) as an alternative (1,14,46).

Surgical approach to management:

- Open heart (aortic) surgery-Mainly used in the absence of aortic valve defect (12,46).

- Minimally invasive endovascular aortic repair- it can be done with endovascular composite consisting of a Dacron stent graft and a transcatheter aortic valve (if aortic valve is compromised) (2,42,45,46).

- Valve sparing aortic root replacement (David procedure) (10,12,14,46).

- Bentall procedure (10,12,41,44,46).

- Sutureless vascular-ring connector with Dacron graft aortic repair.

- Hybrid technique- a combination of stent graft and visceral bypass grafting (10,14,46).

Aortic fenestration has been reported to be used as an interim measure to prevent organ ischemia in cases of organ involvement (22,46). Aortoiliac bypass can also be used when circulation through the iliac vessels are severely compromised to avoid limb ischemia. A case report by John S. Schor, Michael D. Horowitz, et al. (29) detailed a case about a patient with type III aortic dissection (anterograde propagation) and iliac involvement complicated by a clot at the site of aortic bifurcation; which was treated with aortic fenestration and aortoiliac bypass using a knitted Dacron graft. In this case, nonthoracic approach was employed to salvage the limbs and prevent further damage (22,46). When employing surgical management, it is important to evaluate patient’s eligibility for surgery by checking for comorbid conditions and contraindications such as renal insufficiency, advanced age, ischemic cardiomyopathy, diabetes, shock, existing cardiac tamponade and bleeding diathesis.

Prognosis: Approximately 30-40% of patients with acute aortic dissection die after reaching the emergency room. The mortality rate for type A dissections treated medically is estimated to be about 20% within the first 24 hours and 50% at 30 days after initial onset (11,14,46). If surgically managed, Type A dissections incur a mortality rate of 10% after 24 hours and close to 20% at 30 days after repair. On the other hand, for Type B dissections, the 30-day mortality can be as high as 10% for uncomplicated cases. Mortality rate is 1-2% per hour for the first day in patients who do not qualify for surgery. The presence of comorbidities and complications further increases the risk of mortality (1,10,16,18,46).

Follow-up: After the initial management, patients should undergo cardiac rehabilitation, lifestyle modification (smoking cessation, weight loss and avoidance of illicit drugs) and physical therapy if movement is limited (6,46). All patients should be educated on the need for adequate blood pressure control and medication compliance. Serial imaging is recommended with CT scan or MRI at 3-6 months interval to monitor disease progression and check for the emergence of new aneurysms or recurrent dissections (14,34,46). For patients requiring valve replacement with bioprosthetic valve, antiplatelet such as aspirin should be prescribed to prevent clot formation (7,8,46). Although, anticoagulation with warfarin should be added for patients with risk factors such as atrial fibrillation, hypercoagulable state, severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction, history of thromboembolic events; and in patients with subclinical valve thrombosis and no underlying risk factors. Patients with mechanical aortic valve require both aspirin and anticoagulation with warfarin irrespective of their risk stratification (1,22,34,46). For patients requiring anticoagulation with warfarin, early bridging with intravenous unfractionated heparin or subcutaneous heparin should be initiated and target INR should be maintained at 2.0 to 3.0 for 3-6 months or indefinitely depending on the case and type of valve used. For patients with mechanical aortic valve and underlying risks for valve thrombosis, therapeutic INR can be extended to 2.5 to 3.5 (37,38,46). If any contraindication for warfarin exist, aspirin dosage can be increased. Direct oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban) should be avoided in mechanical valves (37,46).

Discussion

Exercise is known to be one of the most effective means of controlling blood pressure. Although all sports have both dynamic and static components, sports requiring a high static demand, such as weight lifting are thought to be associated with a risk of triggering acute aortic dissection (20,46). It is normal for blood pressure to rise to about 200/110 mm Hg during exercise but once it surpasses that level, there is risk of negative cardiovascular outcome (22,30,40,46). Sudden change in blood pressure during weight lifting can predispose the patient to aortic dissection. They have been several cases of aortic dissection reported in weightlifters and individuals who engaged in strenuous exercises prior to their dissection event (17,19,21,22,35,46). It is crucial to note that all types of aortic dissection have been reported to occur in these patients; and that includes type A, and type B aortic dissections (22,46). On the contrary, blood pressure is known to reduce following a short exercise session and more so in physically active individuals that are not premeditated with antihypertensive.(34,45,46) A systematic review and meta-analysis done by Elizabeth Carpio-Rivera, José Moncada-Jiménez, et al. (3) on an heterogeneous sample population, showed that there was a significant reduction in blood pressure irrespective of the participant's initial blood pressure level, gender, physical activity level, antihypertensive drug intake, type of blood pressure measurement, time of day in which the blood pressure was measured, type of exercise performed, and exercise training program with a p value of less than 0.05 for all parameters.

In this particular case report, the patient is an avid weightlifter who developed a type A aortic dissection while weightlifting at the gym. His initial presentation was a popping sensation in the chest, which later evolved into a neurologic sequence of transient bilateral visual loss, paresthesia and other symptoms such as headache, lightheadedness, diaphoresis, pressure-like sensation in his neck, chest and back. He reported no underlying cardiovascular risk factors, use of tobacco, recreational drugs or anabolic steroid use and denies any family history of connective tissue or genetic diseases. There was no report of any recent trauma or injury to the chest wall. Upon evaluation of his vitals, he was hypotensive with diminished pulse on his right upper and lower extremities and no marfanoid features were noted. Lab values were indicative of leukocytosis with acute renal injury secondary to inflammatory response and hypotension respectively. CT angiography of the chest and abdomen showed type A aortic dissection with anterograde propagation of the false lumen to the abdominal aorta. This finding was also supported by cardiac catheterization findings of swirling pattern and with delayed contrast washout. No radiologic chest x-ray findings were noted; head and neck CT scan result came back unremarkable with no ischemic changes seen in the brain. It is crucial to note that a negative chest x-ray does not necessarily exclude aortic dissection as shown in this case. TEE revealed rupture of the left coronary cusp with an ejection fraction of 40% to 45%. Histopathological findings showed no cystic medial necrosis but myxoid degeneration was noted on the aortic wall and cusps. Subsequently, the aortic valve was replaced with a mechanical aortic valve, with a Dacron graft used to replace the aortic root. Post-operatively, the patient was discharged on day 10 with antiplatelet and antihypertensive medications with complete recovery noted at one month follow up. This patient displayed a classic presentation of type A aortic dissection and due to prompt management complications such as aortic rupture, multiple organ failure, cardiac ischemia and renal failure were avoided. This is a clear evidence of type A aortic dissection in a young weightlifter with no underlying traditional risk factors.

Hatzaras I, Tranquilli M, et al. (18) state that “as an initial rule of thumb, it appears that lifting up to one half the individual's body weight is relatively safe, not exceeding a blood pressure of 200 mm Hg, even during the effort cycle of the lifting exercise.” This connotes that weight lifting is safe as long as the patient is educated not to cause too much cardiovascular stress. In Selena Pasadyn, et al. (45) 295 patients were given an online survey to elaborate more about their experience with type A aortic dissection. The eventual response rate on athletic component was 48% (141). Out of 132 patients, 18% stated their doctor did not talk to them about post recovery exercise regimen while 31% (40/129) stated their physicians were uncertain about the types of exercises they should or should not engage in (24). Out of 123 patients, 99 (81%) patients stated they wanted specific recommendations about what exercise regimens were safe. Due to paucity of data on specific exercise recommendations post-event (after an aortic dissection); it is clear that physicians find it difficult to educate their patients on the type and degree of exercise regimens their patients should participate in during their recovery phase. This ambiguity has caused increased isolation among patients post-event; substantial decrease in physical activity and has negatively affected the quality of life. This can also lead to recurrence of dissection if the patient exceeds the required exercise level after prior dissection event. Conversely, preceding the dissection event, out of 80 patients who exercised, 33 (41%) participated in strength work, such as weightlifting or resistance training, and 28.9% (22/76) did engage post-event. 35% (47/136) of patients also reported lifting heavy objects on a regular basis before their dissection, and 9.2% (11/119) did after their dissection. After a successful surgery, only one patient returned to competitive athletics (cycling). This shows that an association exists between strenuous activities such as weightlifting and aortic dissection. Engagement in physical exercise was reduced after dissection as noted. For post-dissection patients, it may be beneficial to take a cautious approach and limit activities that require extreme or maximal exertion extensive sprinting or running, snow shoveling, and mowing the lawn with a non–self-propelled mower. Systolic blood pressure while running at 8 mph may increase by 108 to 162 mm Hg above resting levels but by 26 to 40 mm Hg during brisk walking at 3 mph. Squeezing a hand grip maximally for about 1 minute has shown to increase systolic blood pressure by 50mm Hg and diastolic by 30mm Hg.(6,34,46) With regards to weightlifting, it is important for the post-aortic dissection patients to use a low amount of weight and to stop several repetitions before exhaustion. They should minimize lifting heavy objects, with heavy being defined as objects that require a lot of effort and straining (such as a Valsalva maneuver) to lift (4,6,9,27-28,46). Research by De Souza Nery S, Gomides RS, et al. (46) has shown that blood pressure increased to about 230/165 mm Hg (from 130/80 mm Hg resting blood pressure) when a biceps curl was carried out with heavy weights for the maximum amount of repetitions possible.

Conclusion

Weight-lifting has been demonstrated to improve cardiorespiratory endurance and muscular strength. However, weight-lifting with more than half of the individual’s body weight may be associated with a risk of triggering aortic complications such as aortic dissection. With the growing number of individuals taking up weight training in this era, patient education to minimize cardiovascular stress should be paramount. Although, aortic dissection is less common in the younger population, Physicians need to prioritize it as one of the differentials in young weightlifters without underlying risk factors due to its high mortality. Patients with or without history of connective tissue or genetic disorders and with moderate to high risk for acute aortic dissection may need pre-assessment with an imaging modality such as echocardiography before they start weightlifting or participating in high intensity sports. And individuals with confirmed aortic root dilation should be strongly advised to refrain from strenuous exercises such as weightlifting. These patients may also benefit from blood pressure and heart rate monitoring during their exercise sessions. Exercise recommendations should be made by putting into consideration patient’s age, body mass index, underlying comorbidities and existing risk factors. The duration of exercise should also be modest to avoid unnecessary prolonged cardiovascular stress. For post-event patients (after dissection), it is important that these patients are educated on the type and level of exercise to engage in, and blood pressure should be maintained to avoid recurrence of aortic dissection or even rupture. Regardless of patient’s current health status, it is advisable not to exceed a blood pressure of 200mm/110Hg during peak exercise. Current guidelines and recommendations suggest that patients with prior history of aortic dissection should lift very low weights (less than 50 lbs.) and at submaximal levels; avoid exercise maneuvers that elicit excessive straining (Valsalva) and stop weightlifts several repetitions before fatigue. In addition, recent exercise guideline for the general population stipulates that engaging in aerobic exercise at moderate intensity (such as slow jogging, cycling at a mild pace, walking) at least 30 minutes most days of the week for about 150 minutes per week tend to yield good cardiovascular outcomes with minimal risk for aortic dissection and other cardiovascular complications. Most maximum heart rate prediction equations have shown to overestimate the actual value and some have shown variations with respect to age, gender, physical status and body mass index of participants. Although, the recommended target heart rate regardless of age is 50% to 85% of maximum heart rate; for patients with Marfan syndrome, it is much safer to follow the Marfan foundation physical activity recommendations such as maintaining heart rate at less than 100 bpm for patients not on beta-blockers, and less than 110 bpm for patients on beta-blockers (at moderate intensity).These patients are also encouraged to avoid high intensity exercises such as weightlifting, steep climbing, and activities requiring rapid pressure changes like scuba diving.

References

- David Levy; Amandeep Goyal; Yulia Grigorova; Jacqueline K. Le. Aortic Dissection. (Updated 2019 Dec 16). In: StatPearls (Internet). Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441963/

- Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Aortic dissection. (Accessed April 7th, 2020). Available at: https://columbiasurgery.org/conditions-and-treatments/aortic-dissection (accessed 8/7/20).

- Carpio-Rivera E, Moncada-Jiménez J, Salazar-Rojas W, Solera-Herrera A. Acute Effects of Exercise on Blood Pressure: A Meta-Analytic Investigation. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2016;106(5):422-433. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarzynski MA, Rankinen T, Earnest CP, et al. Measured maximal heart rates compared to commonly used age-based prediction equations in the Heritage Family Study. Am J Hum Biol. 2013;25(5):695-701. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BMJ best practices. Aortic dissection. Available at: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-us/445 (accessed 8/7/20).

- Chaddha A, Kline-Rogers E, Woznicki EM, et al. Cardiology patient page. Activity recommendations for postaortic dissection patients. Circulation. 2014;130(16):e140-e142. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Cardiology. Anticoagulation Strategies After Bioprosthetic Valve Replacement: What Should We Do? Available at: https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2016/12/19/08/44/anticoagulation-strategies-after-bioprosthetic-valve-replacement (accessed 8/7/20).

- Türk UO, Alioğlu E, Nalbantgil S, Nart D. Catastrophic cardiovascular consequences of weight lifting in a family with Marfan syndrome. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2008;36(1):32-34. [PubMed]

- American Heart Association. Target Heart Rates. Available at: https://atgprod.heart.org/HEARTORG/HealthyLiving/PhysicalActivity/GettingActive/Target-Heart-Rates_UCM_434341_Article.jsp (accessed 8/7/20).

- El-Hamamsy I, Ouzounian M, Demers P, et al. State-of-the-Art Surgical Management of Acute Type A Aortic Dissection. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(1):100-109. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeMartino RR, Sen I, Huang Y, et al. Population-Based Assessment of the Incidence of Aortic Dissection, Intramural Hematoma, and Penetrating Ulcer, and Its Associated Mortality From 1995 to 2015. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(8):e004689. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirino AL, Harris S, Lakdawala NK, et al. Role of Genetic Testing in Inherited Cardiovascular Disease: A Review. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(10):1153-1160. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(2):252-289. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Science Direct. Aortic Dissection. (Accessed April 6th, 2020). Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/aortic-dissection (accessed 8/7/20).

- Wasfy MM, Hutter AM, Weiner RB. Sudden Cardiac Death in Athletes. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2016;12(2):76-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukui T. Management of acute aortic dissection and thoracic aortic rupture. J Intensive Care. 2018;6:15. Published 2018 Mar 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwan-Nulla DN, Davidson WR Jr, Grenko RT, Damiano RJ Jr. Aortic dissection in a weight lifter with nodular fasciitis of the aorta. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69(6):1931-1932. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatzaras I, Tranquilli M, Coady M, Barrett PM, Bible J, Elefteriades JA. Weight lifting and aortic dissection: more evidence for a connection. Cardiology. 2007;107(2):103-106. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogan CJ. An aortic dissection in a young weightlifter with non-Marfan fibrillinopathy. Emerg Med J. 2005;22(4):304-305. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itagaki R, Kimura N, Itoh S, Yamaguchi A, Adachi H. Acute type a aortic dissection associated with a sporting activity. Surg Today. 2017;47(9):1163-1171. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragucci MV, Thistle HG. Weight lifting and type II aortic dissection. A case report. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2004;44(4):424-427. [PubMed]

- de Virgilio C, Nelson RJ, Milliken J, et al. Ascending aortic dissection in weight lifters with cystic medial degeneration. Ann Thorac Surg. 1990;49(4):638-642.[CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White A, Broder J, Mando-Vandrick J, Wendell J, Crowe J. Acute aortic emergencies--part 2: aortic dissections. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2013;35(1):28-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacini D, Di Marco L, Fortuna D, et al. Acute aortic dissection: epidemiology and outcomes. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(6):2806-2812. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim HJ, Lee HK, Cho B. A case of acute aortic dissection presenting with chest pain relieved by sublingual nitroglycerin. Korean J Fam Med. 2013;34(6):429-433. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen CH, Liu KT. A case report of painless type A aortic dissection with intermittent convulsive syncope as initial presentation. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(17):e6762. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaidis PT, Rosemann T, Knechtle B. Age-Predicted Maximal Heart Rate in Recreational Marathon Runners: A Cross-Sectional Study on Fox's and Tanaka's Equations. Front Physiol. 2018;9:226. Published 2018 Mar 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinzmann-Filho JP, Zanatta LB, Vendrusculo FM, et al. Maximum heart rate measured versus estimated by different equations during the cardiopulmonary exercise test in obese adolescents. Frequência cardíaca máxima medida versus estimada por diferentes equações durante o teste de exercício cardiopulmonar em adolescentes obesos. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2018;36(3):309-314. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schor JS, Horowitz MD, Livingstone AS. Recreational weight lifting and aortic dissection: case report. J Vasc Surg. 1993;17(4):774-776. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morentin Campillo B, Molina Aguilar P, Monzó Blasco A, et al. Sudden Death Due to Thoracic Aortic Dissection in Young People: A Multicenter Forensic Study. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2019;72(7):553-561.[CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erbel R, Eggebrecht H. Aortic dimensions and the risk of dissection. Heart. 2006;92(1):137-142. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaddha A, Eagle KA, Braverman AC, et al. Exercise and Physical Activity for the Post-Aortic Dissection Patient: The Clinician's Conundrum. Clin Cardiol. 2015;38(11):647-651. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagan PG, Nienaber CA, Isselbacher EM, et al. The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD): new insights into an old disease. JAMA. 2000;283(7):897-903. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braverman AC. Acute aortic dissection: clinician update. Circulation. 2010;122(2):184-188. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh B, Treece JM, Murtaza G, Bhatheja S, Lavine SJ, Paul TK. Aortic Dissection in a Healthy Male Athlete: A Unique Case with Comprehensive Literature Review. Case Rep Cardiol. 2016;2016:6460386. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs JE, Latson LA Jr., Abbara S, et al. Acute chest pain — suspected aortic dissection. American College of Radiology. 1995. Available at: https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69402/Narrative/ (accessed 8/7/20).

- William H Gaasch, Barbara A Konkle. Antithrombotic therapy for surgical prosthetic heart valves and surgical valve repair: Indications. UpToDate. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/antithrombotic-therapy-for-surgical-prosthetic-heart-valves-and-surgical-valve-repair-indications (accessed 8/7/20).

- von Kodolitsch Y, Wilson O, Schüler H, et al. Warfarin anticoagulation in acute type A aortic dissection survivors (WATAS). Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2017;7(6):559-571. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spittell PC, Spittell JA Jr, Joyce JW, et al. Clinical features and differential diagnosis of aortic dissection: experience with 236 cases (1980 through 1990). Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68(7):642-651. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagiwara A, Shimbo T, Kimira A, Sasaki R, Kobayashi K, Sato T. Using fibrin degradation products level to facilitate diagnostic evaluation of potential acute aortic dissection. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2013;35(1):15-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel PD, Arora RR. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of aortic dissection. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;2(6):439-468. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spanos K, Tsilimparis N, Kölbel T. Exercise after Aortic Dissection: to Run or Not to Run. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;55(6):755-756. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu C, Wang T, Li QM, et al. Thoracic endovascular aortic repair for retrograde type A aortic dissection with an entry tear in the descending aorta. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23(4):453-460.e1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes GC. Management of acute type B aortic dissection; ADSORB trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149(2 Suppl):S158-S162. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasadyn S, Roselli E, Blackstone E, Phelan D. Abstract 11126: Acute type a aortic dissections: disruption of lifestyle in competitive athletes. Circulation. 2018;138:A11126. [Abstract]. Available at: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/circ.138.suppl_1.11126 (accessed 8/7/20).

- de Souza Nery S, Gomides RS, da Silva GV, de Moraes Forjaz CL, Mion D Jr, Tinucci T. Intra-arterial blood pressure response in hypertensive subjects during low- and high-intensity resistance exercise. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2010;65(3):271-277. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Pak SC, Asuka E. Acute type A aortic dissection in a young weightlifter: a case study with an in-depth literature review. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2020;21(2):39-53. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc025-20 PDF

Thursday, October 1, 2020 at 8:00AM

Thursday, October 1, 2020 at 8:00AM