Ashley L. Scheffer, MD1,2

Frederick A. Willyerd, MD1,2

Allison L. Mruk, PharmD, BCPPS3

Sarah Patel, BS2

Lucia Mirea, MSc, PhD4

Chasity Wellnitz, RN, BSN, MPH5

Daniel Velez MD2,5

Brigham C. Willis, MD, MEd2,6,7

1Division of Critical Care Medicine, Phoenix Children's Hospital, Phoenix, AZ

2Department of Child Health, University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ

3Department of Pharmacy Services, Phoenix Children's Hospital, Phoenix, AZ

4Department of Biostatistics, Phoenix Children’s Hospital, Phoenix, AZ

5Division of Cardiovascular Surgery, Phoenix Children’s Hospital, Phoenix, AZ

6Division of Cardiovascular Intensive Care, Phoenix Children’s Hospital, Phoenix, AZ

7Department of Pediatrics, University of California Riverside School of Medicine, Riverside, CA

Abstract

Background: In both adults and children, hypotension related to a vasoplegic state has multiple etiologies, including septic shock, burn injury or cardiopulmonary bypass-induced vasoplegic syndrome likely due to an increase in nitric oxide (NO) within the vasculature. Methylene blue is used at times to treat this condition, but its use in pediatric cardiac patients has not been described previously in the literature.

Objective: 1) Analyze the mean arterial blood pressures and vasoactive-inotropic scores of pediatric patients whose hypotension was treated with methylene blue compared to hypotensive controls; 2) Describe the dose administered and the pathologies of hypotension cited for methylene blue use; 3) Compare the morbidity and mortality of pediatric patients treated with methylene blue versus controls.

Design: A retrospective chart review.

Setting: Cardiac ICU in a quaternary care free-standing children’s hospital.

Patients: Thirty-two patients with congenital heart disease who received methylene blue as treatment for hypotension, fifty patients with congenital heart disease identified as controls.

Interventions: None.

Measurements and Main Results: Demographic and vital sign data was collected for all pediatric patients treated with methylene blue during a three-year study period. Mixed effects linear regression models analyzed mean arterial blood pressure trends for twelve hours post methylene blue treatment and vasoactive-inotropic scores for twenty-four hours post treatment. Methylene blue use correlated with an increase in mean arterial blood pressure of 10.8mm Hg over a twelve-hour period (p< 0.001). Mean arterial blood pressure trends of patients older than one year did not differ significantly from controls (p=1.00), but patients less than or equal to one year of age had increasing mean arterial blood pressures that were significantly different from controls (p=0.02). Mixed effects linear regression modeling found a statistically significant decrease in vasoactive-inotropic scores over a twenty-four-hour period in the group treated with methylene blue (p< 0.001). This difference remained significant comparted to controls (p=0.003). Survival estimates did not detect a difference between the two groups (p=0.39).

Conclusion: Methylene blue may be associated with a decreased need for vasoactive-inotropic support and may correlate with an increase in mean arterial blood pressure in patients who are less than or equal to one year of age.

Introduction

One well recognized risk associated with placing patients on cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) during cardiac surgery is vasoplegic syndrome (VS). VS is a constellation of symptoms comprised of hypotension refractory to volume resuscitation and inotropic support, an adequate to high cardiac output state, and low systemic vascular resistance (SVR) (1-4). In adult patients placed on cardiopulmonary bypass the incidence of VS is as high as 4.8%- 8.8% (1,2). For at risk adult populations, such as those who have used heparin, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, or calcium channel blockers pre-operatively, this incidence increases to 44.4%-55.6% (3). Additionally, adult patients who experience vasoplegia after cardiac surgery demonstrate an increased mortality of 10.7%-24% (1,3). Since this syndrome does not respond to conventional fluid resuscitation and vasoactive therapy, patients who experience vasoplegic syndrome often experience poor systemic perfusion that can progress to multisystem organ failure and ultimately death (2).

In both adults and children, hypotension related to a vasoplegic state has multiple etiologies, including septic shock, burn injury or cardiopulmonary bypass-induced vasoplegic syndrome. Various studies have demonstrated an increase in nitric oxide (NO) as the cause of this hypotension (4,6). Vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells contain enzymes that actively produce NO. Vasoplegia is hypothesized to result from the disruption of blood vessel endothelial homeostasis through increased inflammation and dysregulation of the nitric oxide and cyclic guanosine 3’, 5’ monophosphate pathway (cGMP) (5). Published literature demonstrates decreased morbidity and mortality when NO synthesis is inhibited preventing microcirculation impairment (4). Pharmacologic treatments that inhibit NO synthase (NOS) have been developed in an attempt to decrease NO production in disease pathologies where the upregulation of NO causes hypotension. Initial animal and human studies testing nonspecific NOS inhibitors showed NOS inhibition did reduce hypotension and increase systemic vascular resistance (SVR) (8). However, nonspecific NOS inhibition was also associated with severe adverse side effects including myocardial depression with decreased cardiac output, decreased oxygen delivery, and increased mortality, thereby making it unsafe for clinical treatment of vasoplegic syndrome (8).

In order for a pharmacologic agent to successfully inhibit NO, while avoiding serious adverse events, it would theoretically need to inhibit the NO pathway through a different mechanism. In cases of NO upregulation, methylene blue appears to inhibit soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), a downstream biochemical messenger of NO, and ultimately decreases cGMP. cGMP is the final molecular messenger in the NO pathway. Theoretically, decreasing cGMP might avoid the myocardial depression and other adverse side effects seen in nonspecific NO synthase inhibition. Methylene blue is currently approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of methemoglobinemia, but has been studied in the medical literature as an off-label treatment for vasoplegic syndrome in adults. Levin et. al. used methylene blue (MB) as a treatment of CPB-induced vasoplegia in adults and showed a reduction in mortality in those who received the treatment (1,6). In a study treating adults with norepinephrine refractory VS Leyh et.al. demonstrated a subsequently higher SVR and decreased need for catecholamine therapy in the methylene blue treatment group (2,6).

Whether methylene blue is an effective treatment for hypotension in pediatric patients in the cardiovascular intensive care unit remains unknown. There is very limited data published on the use of methylene blue in pediatrics. Methylene blue is used, however, in pediatric cardiovascular intensive care units to treat patients experiencing CPB-induced VS refractory to traditional clinical management based on the decreased mortality reported in the adult literature. Pediatric patients represent a subpopulation whose cardiac pathologies vary greatly from the adults examined in published studies. Due to the variability in cardiac pathology, we aim to describe the type of pathologies for which methylene blue was administered. We examine the association between methylene blue and vital sign trends of pediatric patients, specifically mean arterial blood pressures and vasoactive-inotropic scores. Finally, we compare morbidity and mortality of patients who received methylene blue treatment to controls. In this way, our study investigates if methylene blue is a safe and effective treatment, in conjunction with conventional vasopressor therapy, for hypotension in a pediatric population with congenital heart disease.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective chart review study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Phoenix Children’s Hospital and the Institutional Review Board waived the need for subjects to provide informed consent. Electronic medical records were queried to identify patients who were treated with methylene blue in the cardiac intensive care unit of a single, quaternary care free-standing children’s hospital from February 1st, 2013 to June 30th, 2016. A clinically comparable control sample not treated with methylene blue from the same cardiac intensive care unit and time period was identified through a pharmacy database. Control patients received traditional medical therapy for vasoplegia, which included treatment with a combination of epinephrine, vasopressin, and stress dose steroids. Consistent with previous studies, methylene blue was dosed according to weight using a dose of 1-2mg/kg per institutional pharmacy recommendations. This study included any patient who received methylene blue as treatment for hypotension during the study period. Patients who received methylene blue for a diagnostic or radiographic procedure instead of treatment for hypotension were excluded.

For both treated and control patients, trained investigators manually extracted demographic data, vital sign data, and vasoactive-inotropic scores (VIS) during a designated collection period. VIS composite scores reflecting the amount of inotrope and vasopressor support required by infants postoperatively and include dopamine, dobutamine, epinephrine, milrinone, vasopressin, and norepinephrine. As methylene blue has a half-life of five hours, mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) values were collected at the time the medication was administered and at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 hours post treatment, more than two half-lives of the drug. Similarly, VIS were collected at the time of treatment and at 6, 12, 18, and 24 hours post treatment, more than four half-lives of methylene blue. The control cohort had similar electronic medical record data collected for assessment. Morbidity and mortality data for both groups was obtained from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database. Time-to-death in days was computed from the date of surgery to the date of death from all causes.

The distributions of demographic data, baseline clinical factors, cardiac surgical repair, and post-operative conditions were summarized using descriptive statistics for both the methylene blue and control group. Comparison between groups was performed using parametric (Pearson Chi-square test, T-test) or non-parametric (Fisher exact, Wilcoxon rank sum) analyses as appropriate for the data distribution. Similar analysis compared the amount of fluid resuscitation and steroid treatment between patients in the methylene blue group and the control group. Univariate mixed effect models were used to estimate the change in MAP and VIS over time while controlling for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support. Post-operative ventilator support, post-operative complications, length of stay, and mortality were described and compared between the two groups using appropriate statistical tests as listed above. Overall survival was displayed for each group using Kaplan-Meier curves and compared between the two groups using the Log-rank test. All statistical tests were 2-sided with significance evaluated at the 5% level. Analyses were performed using the statistical package SAS (SAS Institute 2011) and STATA (7).

Results

During the study period, methylene blue was administered on thirty-nine occasions to treat thirty-two unique patients. After excluding four patients treated with methylene blue for diagnostic procedures instead of hypotension, the final sample treated with methylene blue included twenty-eight unique patients, of which seven patients were treated twice, resulting in a total of thirty-five methylene blue treatments. Repeat treatments in the same patients were treated as independent events as they were during separate clinical encounters. Indications for using methylene blue included hypotension secondary to cardiogenic shock in seven patients (25%), post cardiopulmonary bypass vasoplegia in sixteen patients (57%), ECMO decannulation hemodynamic instability in two patients (7%), and septic shock in three patients (11%) (Supplemental Digital Content 1). Doses of methylene blue ranged from 0.3mg/kg- 2mg/kg with an average dose of 1.1mg/kg for the treatment cohort.

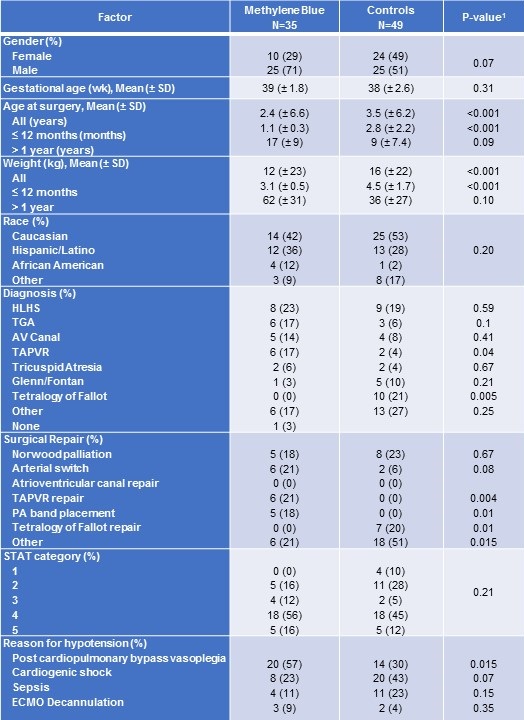

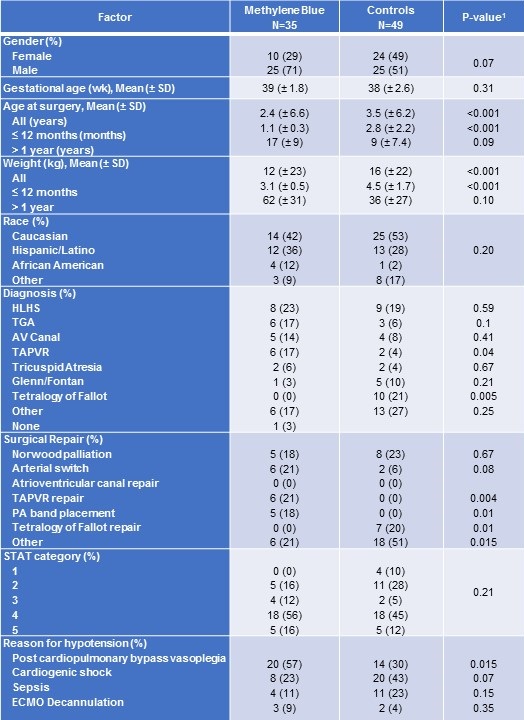

Among patients less than one year of age, those treated with methylene blue received surgery at a significantly younger age and had a lower mean weight at the time of surgery than did controls (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics for patients treated with methylene blue and controls.

SD = standard deviation

1P-value from Fisher exact test for categorical variables or Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous measures.

Congenital heart disease diagnosis was comparable between the two groups, except for tetralogy of Fallot with zero patients (0%) among the methylene blue group, but ten patients (21%) in the control group (Table 1). No significant differences were detected in disease severity as measured by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STAT) Category.

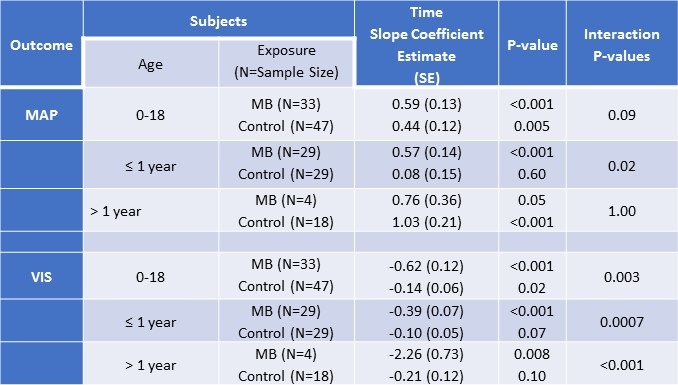

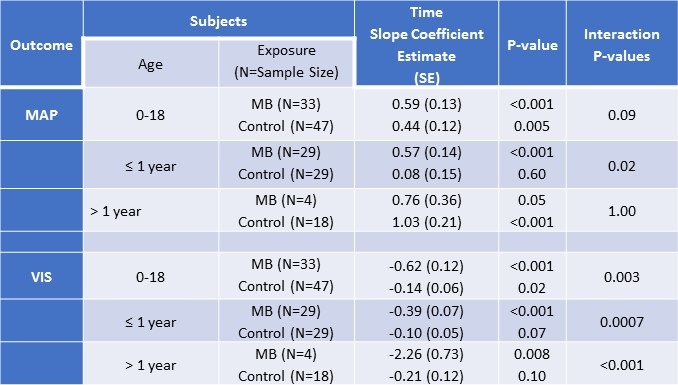

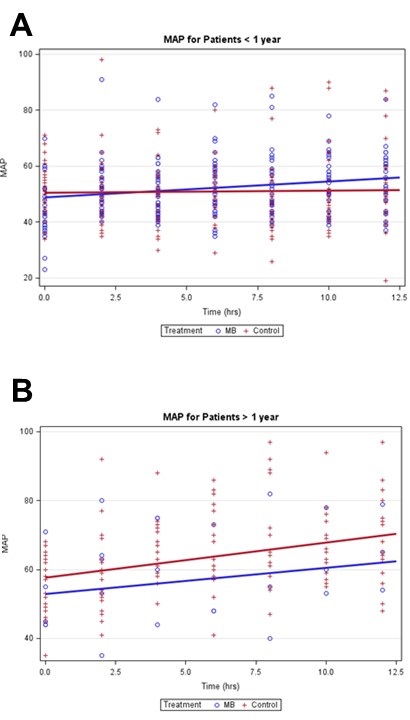

At baseline mean arterial blood pressures (mean ± SD) were significantly lower (T-test p-value = 0.004) in patients treated with methylene blue (45mmHg ± 10) compared to controls (52mmHg ± 10). The average increase in mean arterial blood pressure from baseline to twelve hours did not vary significantly (T-test p-value = 0.40) between methylene blue patients (8.5mmHg ± 13) and controls (5.6mmHg ± 16). However, when analyses were restricted to subjects less than one year of age, a larger increase in mean arterial blood pressure was suggested (T-test p-value = 0.08) for MB patients (8.5 ± 14) compared to controls (1.4 ± 16). Mixed effects linear models examining MAP measurements over time among patients ≤ 1 year with adjustment for ECMO, confirmed a significant increase in MAP over time for those who were treated with MB (slope coefficient = 0.57, p-value <0.001) whereas no trend in MAP values was detected for control patients ≤ 1 year (slope coefficient = 0.08, p-value 0.6). Among patients > 1 year, MAP increased over time for both MB and controls, with no detectable difference between the slopes estimates (Table 2).

Table 2. Mixed effects linear regression analyses examining time trends in mean arterial pressure (MAP) and vasoactive-inotropic score (VIS) of patients treated with methylene blue and controls by age.

MAP= mean arterial pressure; VIS= vasoactive-inotropic scores; SE = standard error

*All models included a random patient-level intercept, assumed unstructured correlation, and were adjusted for ECMO.

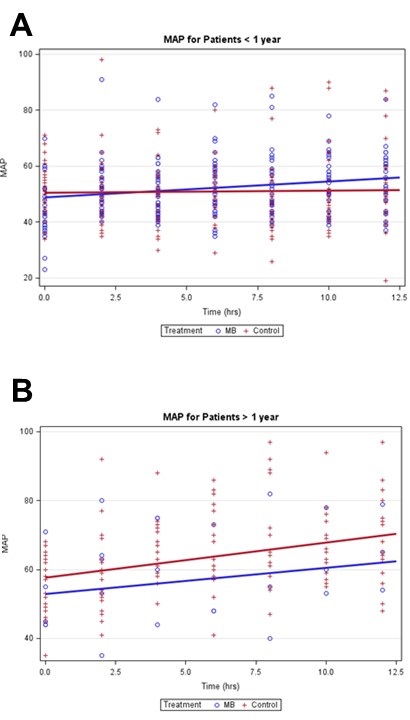

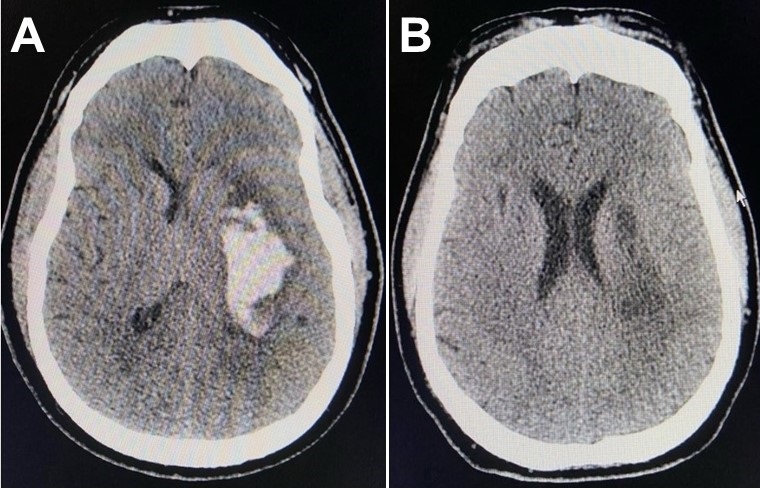

Figures 1A and 1B show the MAP measurements over time, and the estimated slopes for MB and control patients adjusted for clustering and ECMO.

Figure 1. Mean arterial blood pressure mixed effects linear regression models stratified by age.

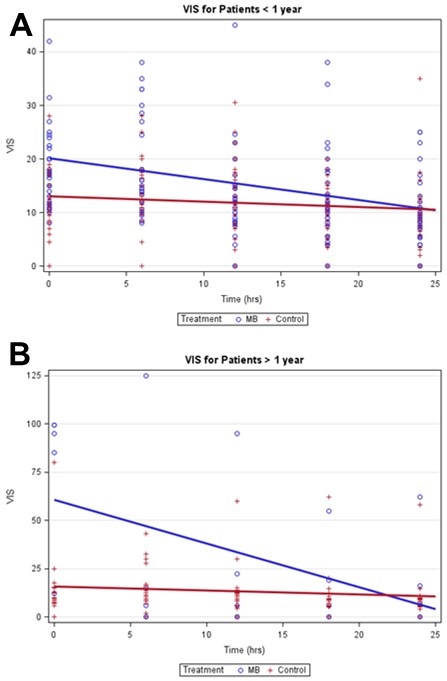

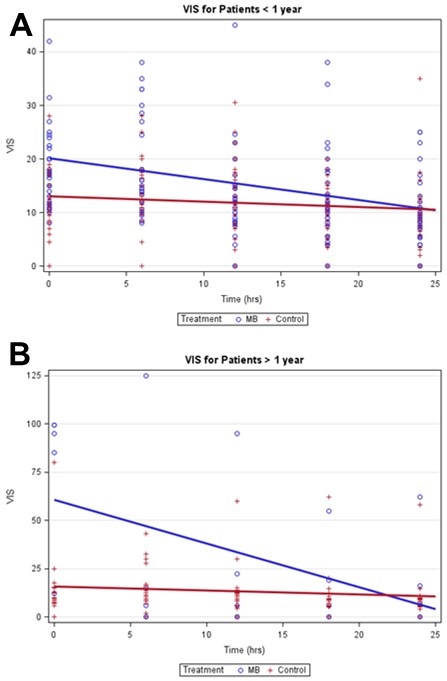

The mean VIS at baseline was significantly higher in MB (27 ± 26) compared to control (12 ± 11) patients (T-test p-value = 0.002). From baseline to 24 hours, MB patients had a significantly larger mean decrease in VIS than controls overall (T-test p-value <0.006). Analyses stratified by age detected a significant negative trend in VIS for MB patients, especially among MB patients > 1 year (Table 2). Weak negative trends in VIS were detected among controls (Figures 2A and 2B).

Figure 2. Vasoactive inotropic score mixed effects linear regression models stratified by age.

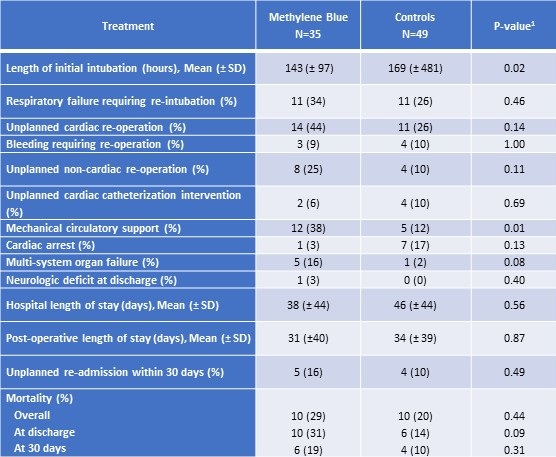

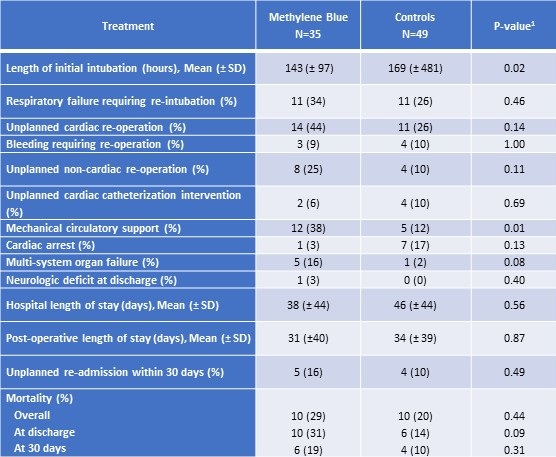

Patients treated with methylene blue were extubated approximately twenty-four hours sooner than those in the control group (Table 3).

Table 3. Outcomes among patients treated with methylene blue and controls.

SD = standard deviation

1P-value from Fisher exact test for categorical variables or Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous measures

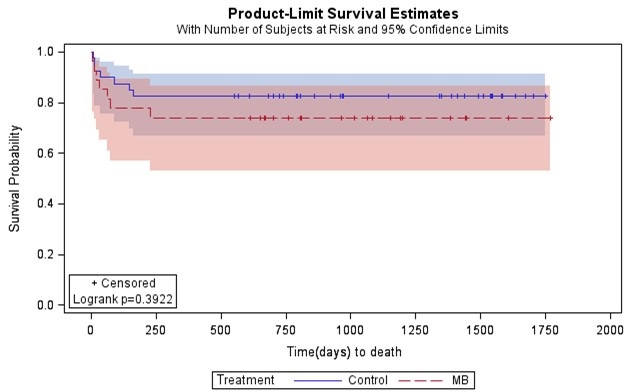

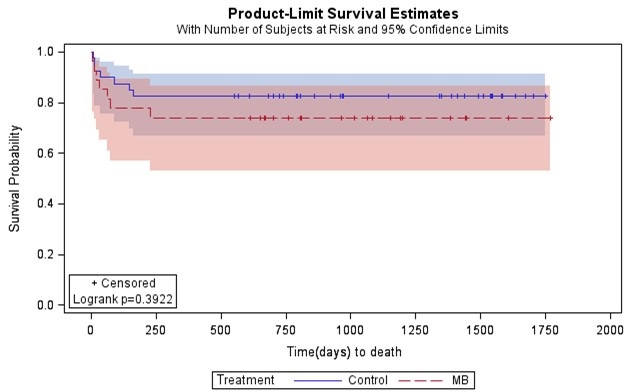

However, methylene blue patients had higher incidence of ECMO support and multisystem organ failure, but a lower incidence of cardiac arrest compared to controls (Table 3). There were no reported adverse effects from methylene blue use. Mortality at thirty days post operatively did not vary significantly between groups (Table 3). At discharge, methylene blue patients had notably higher mortality compared to controls (31% vs. 14%), but statistical significance was not reached (Table 3). There was no difference in length of ICU stay or hospital length of stay between the two groups (Table 3). Furthermore, no significant differences in survival were detected between the methylene blue patients and control patients (Figure 3; Log-rank p-value= 0.39); however, our study was not powered adequately to show equivalence of a clinical outcome.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for patients treated with methylene blue versus controls.

Discussion

Overall, we found that methylene blue use was associated with a decreased need for vasoactive-inotropic support when compared to the control cohort and may correlate with an increase in mean arterial blood pressure over time, specifically in those patients who are less than or equal to one year of age. Vasoplegia results in increased mortality because it often remains resistant to standard clinical interventions such as administration of intravenous fluids and the use of multiple inotropic medications leading to refractory shock and poor oxygen delivery in patients who experience it (2). If a patient’s shock state is unable to be reversed, vasoplegic syndrome (VS) could lead to increased mortality in vulnerable populations such as pediatric patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass for cardiac surgery. In our study, we demonstrated that methylene blue use was associated with an increase in mean arterial blood pressure over a twelve-hour period and a decrease in vasoactive-inotropic scores over a twenty-four-hour period. When compared with controls, the decrease in vasoactive-inotropic score maintained statistical significance in all ages, but mean arterial blood pressure trends were only significant compared to controls in children less than or equal to one year of age. These results support the theory that methylene blue could be an effective treatment for vasoplegia in the pediatric population, although more prospective studies would be needed to verify causation. However, as mentioned above, given the retrospective nature of our study, the difficulty in identifying a more completely matched control cohort (especially for the group of patients <1 year of age), and the limited numbers, such conclusions must be tempered until such trials are performed.

During our evaluation we noted that the increase in mean arterial blood pressure was only statistically significant when ages were stratified. In children older than a year, the increasing mean arterial blood pressure trends observed over time may have resulted from improvement of low cardiac output syndrome after cardiopulmonary bypass since both the control and treatment cohort mixed effects linear regression models had similarly increasing slopes that were not statistically different from each other. In ages less than or equal to one year, however, the control cohort mixed effects linear regression model did not show any trend toward increasing mean arterial blood pressures. Additionally, the methylene blue cohort had an initial lower average mean arterial blood pressure and a statistically significant trend up in mean arterial pressures over a twelve-hour period. Although this subgroup analysis was a smaller sample, the difference in the two regression models suggests that there may be a correlation between the use of methylene blue and increasing mean arterial blood pressures in children less than or equal to one year of age.

Both our treatment cohort and our control cohort were very heterogeneous in certain demographic characteristics, specifically in age and weight, but are very typical of the clinical patient population. Normal values for vital signs such as mean arterial blood pressure vary greatly between ages, which can make statistical interpretation of these vital sign trends difficult. In our study, heterogeneity of age resulted in variability of mean arterial blood pressure data that limited our interpretation of vital signs trends unless age groups were stratified. Ideally, we would have examined all vital sign trends stratified by age to improve the accuracy of our interpretation. However, our population was too small to appropriately power such a subgroup analysis.

Attempting to identify the control group without introducing bias may also have contributed to the difference seen in mean arterial blood pressure trends between the methylene blue cohort and the control cohort. There are multiple factors that control mean arterial blood pressure and vasoactive-inotropic scores. In an attempt to limit cofounding factors, a control group was selected using a pharmacy database that identified patients who received both vasoactive-inotropic treatment and stress dose steroids to treat refractory hypotension after cardiac surgery to find a clinically comparable cohort. The control cohort varied slightly in demographic characteristics, but did not appear statistically different in fluid resuscitation or steroid use (Supplemental Digital Content 2). However, this remains a significant limitation of the current study, given its small numbers, heterogeneous population, and difficulty identifying a better-matched control group. In the future, a prospective, randomized trial of methylene blue in this population could address this.

For adult patients who experienced vasoplegic syndrome, multiple studies have demonstrated an overall reduction in mortality in patients who were treated with methylene blue (1,2,6). However, unlike the adult studies, our study did not find any statistically significant survival difference between the methylene blue cohort and the control cohort. Our study did demonstrate, however, that methylene blue was not associated with increased mortality. Patients treated with methylene blue were also extubated sooner that patients in the control cohort. Speculatively, methylene blue treatment may have been associated with less cardiopulmonary liability, increasing the clinician’s confidence to wean toward extubation sooner than the control group. In addition, our study showed a higher incidence of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support and multisystem organ failure in the methylene blue group as compared to controls. This is likely a result of the high incidence of refractory hypotension and severe shock that led to the use of methylene blue. There was no difference between the two groups in their number of intensive care days or hospital length of stay. No adverse side effects directly attributable to methylene blue were reported in any of our cases, indicating it is a potentially safe treatment for vasoplegic syndrome.

Our study was designed as a retrospective chart review and therefore had limitations inherent with this design. We examined blood pressure trends of any pediatric patient that was given methylene blue for hypotension, regardless of the pathophysiology. Accurately pinpointing the justification for methylene blue treatment retrospectively was difficult especially given the complex nature of the patients’ disease processes, resulting in multiple reasons for hypotension cited in the electronic medical record. We could not accurately limit our patient selection to patients with cardiopulmonary bypass-induced vasoplegia without introducing selection bias and therefore decided to look at all patients who were treated with methylene blue during the study period. Furthermore, limiting our sample size to only those patients who received methylene blue as treatment for post cardiopulmonary bypass vasoplegic syndrome would have resulted in a sample size too small to appropriately power our study.

The definition of vasoplegia requires patients to maintain a high cardiac output state. There were no objective measurements of cardiac output that could be identified retrospectively, thus our study relied on clinician estimation of high cardiac output. In nearly thirty percent of the methylene blue cohort, methylene blue was used as treatment for hypotension that was related to low cardiac output or cardiogenic shock, not vasoplegia. The adult studies that showed a difference in mean arterial blood pressures as well as mortality of patients were examining methylene blue treatment of hypotension secondary to vasoplegic syndrome specifically. Additional prospective studies in pediatric patients are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of methylene blue in treating vasoplegic syndrome.

Conclusion

Methylene blue may be a safe and effective treatment for vasoplegia in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease. Methylene blue use was associated with a decreased need for vasoactive-inotropic support when compared to the control cohort and may correlate with an increase in mean arterial blood pressure over time, specifically in those patients who are less than or equal to one year of age. There was a statistically significant decrease in ventilator days between the methylene blue cohort and the control cohort. There was no difference in survival estimates between those patients who received methylene blue versus controls.

References

- Levin RL, Degrange MA, Bruno GF, Del Mazo CD, Taborda DJ, Griotti JJ, Boullon FJ. Methylene blue reduces mortality and morbidity in vasoplegic patients after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004 Feb;77(2):496-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyh RG, Kofidis T, Strüber M, Fischer S, Knobloch K, Wachsmann B, Hagl C, Simon AR, Haverich A. Methylene blue: the drug of choice for catecholamine-refractory vasoplegia after cardiopulmonary bypass? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003 Jun;125(6):1426-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozal E, Kuralay E, Yildirim V, Kilic S, Bolcal C, Kücükarslan N, Günay C, Demirkilic U, Tatar H. Preoperative methylene blue administration in patients at high risk for vasoplegic syndrome during cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005 May;79(5):1615-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evora PR, Alves Junior L, Ferreira CA, Menardi AC, Bassetto S, Rodrigues AJ, Scorzoni Filho A, Vicente WV. Twenty years of vasoplegic syndrome treatment in heart surgery. Methylene blue revised. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc. 2015 Jan-Mar;30(1):84-92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner I, Guo F, Bogert NV, Stock UA, Meybohm P, Moritz A, Beiras-Fernandez A. Methylene blue modulates transendothelial migration of peripheral blood cells. PLoS One. 2013 Dec 10;8(12):e82214. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar S, Zedan A, Nugent K. Cardiac vasoplegia syndrome: pathophysiology, risk factors and treatment. Am J Med Sci. 2015 Jan;349(1):80-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAS Institute Inc. 2011. Base SAS® 9.3 Procedures Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

- Farina Junior JA, Celotto AC, da Silva MF, Evora PR. Guanylate cyclase inhibition by methylene blue as an option in the treatment of vasoplegia after a severe burn. A medical hypothesis. Med Sci Monit. 2012 May;18(5):HY13-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Víteček J, Lojek A, Valacchi G, Kubala L. Arginine-based inhibitors of nitric oxide synthase: therapeutic potential and challenges. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:318087. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutledge C, Brown B, Benner K, Prabhakaran P, Hayes L. A Novel Use of Methylene Blue in the Pediatric ICU. Pediatrics. 2015 Oct;136(4):e1030-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corral-Velez V, Lopez-Delgado JC, Betancur-Zambrano NL, Lopez-Suñe N, Rojas-Lora M, Torrado H, Ballus J. The inflammatory response in cardiac surgery: an overview of the pathophysiology and clinical implications. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2015;13(6):367-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Scheffer AL, Willyerd FA, Mruk AL, Patel S, Mirea L, Wellnitz C, Velez D, Willis BC. Methylene blue treatment of pediatric patients in the cardiovascular intensive care unit. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2021;23(1):8-17. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc022-21 PDF

Presented, in part, in abstract form at the 2018 Society of Critical Care Medicine Conference in February 25-28, 2018, San Antonio, TX.

The authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Sunday, July 11, 2021 at 8:00AM

Sunday, July 11, 2021 at 8:00AM