Fatal Consequences of Synergistic Anticoagulation

Thursday, May 31, 2018 at 8:00AM

Thursday, May 31, 2018 at 8:00AM Payal Sen, MD1

Uddalak Majumdar, MD2

Patrick Rendon, MD1

Ali Imran Saeed, MD1

Akshay Sood, MD1

Michel Boivin, MD1

1University of New Mexico

Albuquerque, NM US

2Cleveland Clinic Foundation

Cleveland, OH USA

Abstract

Objective: Novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) are increasingly being preferred by clinicians (and patients) because they have a wide therapeutic window and therefore do not require monitoring of anticoagulant effect. Herein, we describe the unfortunate case of a patient who had fatal consequences as a result of switching from warfarin to rivaroxaban.

Case Summary: A 90-year-old Caucasian woman, with atrial fibrillation on chronic anticoagulation with warfarin, was admitted to the hospital for pneumonia. She was treated with levofloxacin. In the same admission, her warfarin was switched to rivaroxaban. On Day 3 after the switch, her INR was found to be 6, and she developed a cervical epidural hematoma from C2 to C7. She ultimately developed respiratory arrest, was put on comfort care and died.

Discussion: Rivaroxaban and warfarin are known to have a synergistic anticoagulant effect, usually seen shortly after switching. Antibiotics also increase the effects of warfarin by the inhibition of metabolizing isoenzymes. It is hypothesized that these two effects led to the fatal cervical spinal hematoma.

Conclusion: The convenience of a wide therapeutic window and no requirement of laboratory monitoring makes the NOACs a desirable option for anticoagulation. However, there is lack of data and recommendations on how to transition patients from Warfarin to NOACs or even how to transition from one NOAC to another. Care should be taken to ensure continuous monitoring of anticoagulation when stopping, interrupting or switching between NOACS to avoid the possibility of fatal bleeding and strokes.

Introduction

Novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) are increasingly being preferred by clinicians (and patients) because they have a wide therapeutic window and therefore do not require monitoring of anticoagulant effect. They have also shown greater efficacy and safety when compared to warfarin (1). The choice among the novel oral anticoagulants depends on their different pharmacokinetic profile, patients' stroke and bleeding risk, comorbidities, drug tolerability and costs and, finally, patients' preferences (2). There is however, paucity of evidence regarding the process of switching from warfarin to a NOAC, from one NOAC to the other, and the consequent ‘synergism’ (3). Herein, we describe the unfortunate case of a patient who had fatal consequences as a result of switching from warfarin to rivaroxaban. We also wish to highlight the adverse effects that antibiotic interaction can have with both warfarin and the NOACS (4).

Case Report

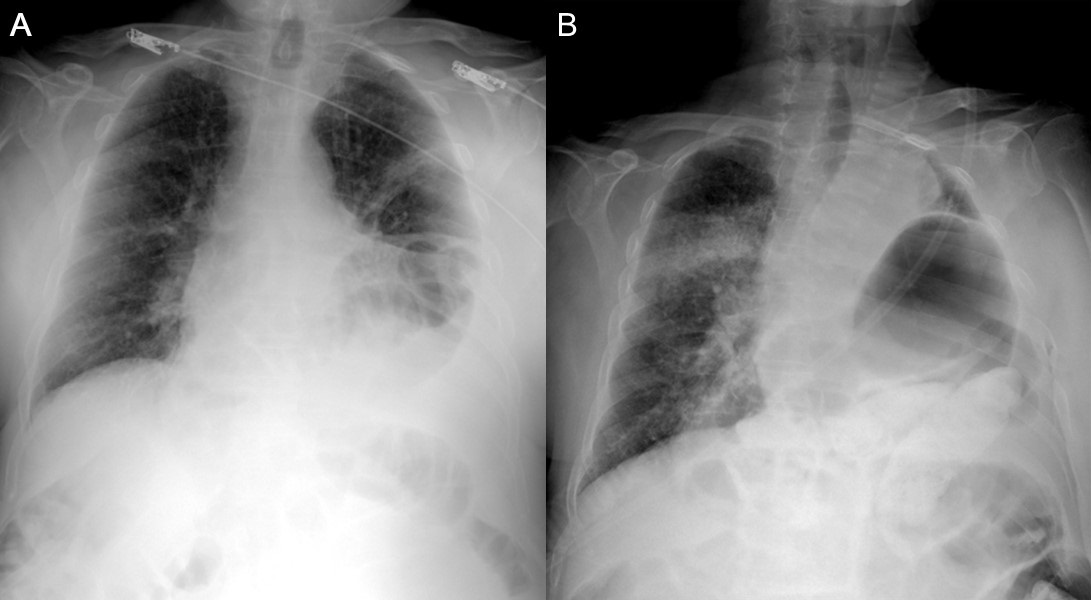

A 90-year-old Caucasian woman, who resided in a nursing home was admitted to the hospital with chief complaints of fever and confusion for 2 days. She also had intermittent cough, but denied headache, blurry vision, dysuria, diarrhea and constipation. Past medical history was significant for non-valvular atrial fibrillation, for which she was on therapeutic anticoagulation with warfarin. Family history and social history were not significant. Vitals revealed a temperature of 100 F and physical exam was positive for crackles in the right lower lobe of the lung. Her white count was elevated at 16 x 103/µL, and hepatic and renal function were both normal. Chest x-ray revealed a right sided lower lobe pneumonia. She was admitted to the hospital for acute metabolic encephalopathy due to sepsis secondary to hospital associated pneumonia and was initially given a dose of vancomycin and piperacillin tazobactam, which was later narrowed to levofloxacin.

Hospital Course

On day 2, the patient’s disorientation had improved marginally and her white count had also reduced to 11. Her INR was therapeutic on warfarin and she underwent transesophageal echocardiography and cardioversion for symptomatic atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular rate. After a long discussion with the patient and her family, it was decided to switch from warfarin to rivaroxaban, to avoid the hassle of frequent INR monitoring.

On Day 3, the patient suddenly developed tachypnea, hypotension and dysarthria after receiving the second dose of rivaroxaban. Rapid Response had to be called. Vitals revealed blood pressure of 92/52, respiratory rate 20, and heart rate of 84 with pulse oximetry showing 92% on 2 liters nasal cannula.

Neurological Examination

Cognition was relatively normal. Patient was alert and oriented X 3.

Motor exam: The patient was quadriplegic.

Touch, pain, and pressure sensations were absent (0/4) below C3-C4.

Reflexes were diminished (¼) and she had absolutely no feeling of any noxious stimuli. Babinsky' s sign was negative.

Urgent Labs on Day 3 (current day)

Arterial blood gases: PaO2 of 62 on 3 liters oxygen via Nasal cannula, PaCO2 of 78.

International Normalized Ratio (INR): 6, prothrombin time was 64.2 seconds.

Radiographic Imaging

Figure 1. Computed tomography scan of the neck revealed posterior cervical epidural hematoma (arrow) from C2 to C7 with cord compression.

Figure 2. Posterior epidural hematoma (arrow) extending from C2-3 through approximately C6-7, which caused significant spinal stenosis.

The patient was then rushed to the neurosurgical ICU. Neurosurgery was consulted and recommended reversing the anticoagulation and taking the patient for emergency surgical evacuation of the hematoma. However, on further discussion with the family, it was revealed that the patient’s earlier wishes had been to never be bedbound and paralyzed. Since she was a 90-year-old patient, chronically debilitated, with a do not resuscitate code status, the ultimate decision was to place her on comfort care. Patient passed away 24 hours later.

Discussion

Rivaroxaban and warfarin are known to have a synergistic anticoagulant effect, usually seen shortly after switching (5). Antibiotics also increase the effects of warfarin by the inhibition of metabolizing isoenzymes (4). It is hypothesized that these two effects led to the fatal cervical spinal hematoma.

For decades, vitamin K antagonists like warfarin have been the agent of choice for oral anticoagulation in different clinical conditions. However, the disadvantages of warfarin are that it needs frequent INR monitoring, has a narrow therapeutic window and interacts with multiple food substances and drugs (6). Warfarin is also known to cause major bleeding. The NOACS (novel oral anticoagulants) such as the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran, and Factor Xa Inhibitors like rivaroxaban, edoxaban and apixaban have been developed almost fifty years after the approval of warfarin (7). These NOACS have more predictable pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, fewer drug and dietary interactions and have the added advantage of not requiring frequent laboratory monitoring (7,8). Clinicians are increasingly using these NOACS to replace Vitamin K antagonists for multiple indications like the prevention of thromboembolic complications in atrial fibrillation, treatment of Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), and thromboprophylaxis during orthopedic surgery (9).

Rivaroxaban, which is an oxazolidinone derivative, inhibits both free Factor Xa and Factor Xa bound in the prothrombinase complex (10). It is a highly selective Factor Xa inhibitor and has high oral bioavailability, with rapid onset of action and a predictable pharmacokinetic profile across a wide spectrum of patients with respect to gender, age, weight and race (11). There is paucity of data on how to safely switch from warfarin to rivaroxaban. Expert opinion is to switch 24 hours after INR < 3 (3). There is only one observational matched-cohort study of switching from warfarin to rivaroxaban and results supported present practices (3). It analyzed a French registry and fluindidione (not warfarin) was the Vitamin K Antagonist in about 90% of the study subjects. In another study of in silico effects, a post-switch synergistic anticoagulant effect has also been observed and a nomogram has been developed for switching to Rivaroxaban, based on INR for Caucasian and Japanese patients (5). INR is affected variably by rivaroxaban and cannot be used as a marker for its anticoagulant effect (12). Laboratory monitoring of anticoagulant effect of NOACs needs to be considered, since INR is unsuitable for this (13).

Some of the manufacturers offer guidance relating to switching from warfarin to NOACs:

- To apixaban: warfarin should be discontinued and apixaban started when the INR is <2.0.

- To dabigatran: warfarin should be discontinued and dabigatran started when the INR is <2.0.

- To rivaroxaban: warfarin should be discontinued and rivaroxaban started when the INR is <3.0.

With longer experience with these NOACs in Europe, the European Heart Rhythm Association does make slightly different recommendations than those in the United States (14). Again, looking at switching from a vitamin K antagonist to a NOAC, the group suggests:

- The NOAC can be immediately initiated once the INR is <2.0.

- If the INR is 2.0 to 2.5, the NOAC can be started immediately or (preferably) the next day.

- If the INR is >2.5, use agent pharmacokinetics to estimate the time for the next INR.

As for moving from parenteral anticoagulation to a NOAC, the European recommendation is:

- For unfractionated heparin (UFH), start the NOAC once the UHF is discontinued.

- For low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH), start the NOAC when the next dose of LMWH would have been due.

Hence, switching vitamin K antagonists to newer direct oral anticoagulants (NOACs) is becoming routine now, since the latter are thought to have a reduced incidence of intracranial bleeding (15). This case teaches us that the synergistic effect and interactions with antibiotics should be kept in mind during switching and when possible, nomograms should be used. Further study is required regarding bridging doses, bridging periods and population-specific dosing.

Conclusion

The convenience of a wide therapeutic window and no requirement of laboratory monitoring makes the NOACs a desirable option for anticoagulation. However, there is lack of data and recommendations on how to transition patients from a vitamin K antagonist to NOACs or even how to transition from one NOAC to another. Care should be taken to ensure continuous monitoring of anticoagulation when stopping, interrupting or switching between NOACS to avoid the possibility of fatal bleeding and strokes. Further trials are also needed to test for appropriate laboratory monitoring of the NOACs. Also, caution must be used whilst using antibiotics with the NOACs, since their interaction can often increase the efficacy of the NOACs and lead to fatal bleeding, like in our patient.

References

- Prisco D, Cenci C, Silvestri E, Ciucciarelli L, Di Minno G. Novel oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: which novel oral anticoagulant for which patient? J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2015 Jul;16(7):512-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego P, Roldan V, Lip GY. Novel oral anticoagulants in cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2014 Jan;19(1):34-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouillon K, Bertrand M, Maura G, Blotiere PO, Ricordeau P, Zureik M. Risk of bleeding and arterial thromboembolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation either maintained on a vitamin K antagonist or switched to a non-vitamin K-antagonist oral anticoagulant: a retrospective, matched-cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2015 Apr;2(4):e150-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane MA, Zeringue A, McDonald JR. Serious bleeding events due to warfarin and antibiotic coprescription in a cohort of veterans. Am J Med. 2014 Jul;127(7):657-663.e2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burghaus R, Coboeken K, Gaub T, Niederalt C, Sensse A, Siegmund HU, Weiss W, Mueck W, Tanigawa T, Lippert J. Computational investigation of potential dosing schedules for a switch of medication from warfarin to rivaroxaban-an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor. Front Physiol. 2014 Nov 7;5:417. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezekowitz MD, Aikens TH, Brown A, Ellis Z. The evolving field of stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2010 Oct;41(10 Suppl):S17-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendell J, Zahir H, Matsushima N, Noveck R, Lee F, Chen S, Zhang G, Shi M. Drug-drug interaction studies of cardiovascular drugs involving P-glycoprotein, an efflux transporter, on the pharmacokinetics of edoxaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2013 Oct;13(5):331-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogata K, Mendell-Harary J, Tachibana M, Masumoto H, Oguma T, Kojima M, Kunitada S. Clinical safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of the novel factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2010 Jul;50(7):743-53. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer KA. Recent progress in anticoagulant therapy: oral direct inhibitors of thrombin and factor Xa. J Thromb Haemost. 2011 Jul;9 Suppl 1:12-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roehrig S, Straub A, Pohlmann J, Lampe T, Pernerstorfer J, Schlemmer KH, Reinemer P, Perzborn E. Discovery of the novel antithrombotic agent 5-chloro-N-({(5S)-2-oxo-3- [4-(3-oxomorpholin-4-yl)phenyl]-1,3-oxazolidin-5yl}methyl)thiophene- 2-carboxamide (BAY 59-7939): an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2005 Sep 22;48(19):5900-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson BI, Borris LC, Dahl OE, Haas S, Huisman MV, Kakkar AK, Muehlhofer E, Dierig C, Misselwitz F, Kälebo P; ODIXa-HIP Study Investigators. A once-daily, oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor, rivaroxaban (BAY 59-7939), for thromboprophylaxis after total hip replacement. Circulation. 2006 Nov 28;114(22):2374-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favaloro EJ, Lippi G. The new oral anticoagulants and the future of haemostasis laboratory testing. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22(3):329-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindahl TL, Baghaei F, Blixter IF, Gustafsson KM, Stigendal L, Sten-Linder M, Strandberg K, Hillarp A; Expert Group on Coagulation of the External Quality Assurance in Laboratory Medicine in Sweden. Effects of the oral, direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran on five common coagulation assays. Thromb Haemost. 2011 Feb;105(2):371-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidbuchel H, Verhamme P, Alings M, Antz M, Hacke W, Oldgren J, Sinnaeve P, Camm AJ, Kirchhof P; European Heart Rhythm Association. European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of new oral anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2013 May;15(5):625-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldeira D, Barra M, Pinto FJ, Ferreira JJ, Costa J. Intracranial hemorrhage risk with the new oral anticoagulants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol. 2015 Mar;262(3):516-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Sen P, Majumdar U, Rendon P, Saeed AI, Sood A, Boivin M. Fatal consequences of synergistic anticoagulation. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2018;16(5):289-95. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc058-18 PDF