Organ Failure in Acute Pancreatitis and Its Impact on Outcome in Critical Care

Friday, May 15, 2015 at 8:00AM

Friday, May 15, 2015 at 8:00AM Namrata Maheshwari, MD, IDCCM

Arun Kumar, MD

Zafar A Iqbal, MD

Amit K Mandal, DNB,DTCD

Abhishek Vyas, MBBS

Jai D Wig, MS

Department of Critical Care Medicine and Pulmonology

Fortis Hospital

Mohali, Punjab, 160062

India

Abstract

The most important determinant of mortality in acute pancreatitis is organ failure (OF). The aim of this prospective observational study was to determine the incidence of organ failure in acute pancreatitis and its relation with the extent of necrosis and outcome. Sixty-one patients were divided into 3 groups: no organ failure (NOF), transient organ failure (< 48 hrs) (TOF) or persistent organ failure (> 48 hrs) (POF). Of 61 patients, 30 patients had no organ failure (49.1%), while 11 patients (18%) had TOF and 20 patients (32.7%) had POF. The mean age was 46.5 yrs with male predominance. Pulmonary and renal failures were the most common (32%), followed by CVS (cardiovascular system), coagulation system and CNS (central nervous system). Fourteen (46.4%) patients had one or two OF, 17 (56.6%) had more than two OF. There were no deaths in patients with up to two organ failures but a 70% (7) death rate in those with three organ involvement, 80% (4) with four and 100% with five OF. The percentage of pancreatic necrosis was evaluated for its relationship with organ failure. In the NOF group 19 (63.3%) patients had no necrosis, as compared to 11 patients with necrosis in TOF and POF groups (35.4%). Out of 61 patients, 13 patients died. All 13 patients who expired belonged to the POF group (p <.001). Early persisting and deteriorating organ failure had the worst outcomes. There was an increase in mortality with an increasing number of organs involved. The extent of necrosis was directly related with incidence of organ failure.

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is characterized by a variable clinical course varying from a mild self-limited disease (80-90%) to a clinically severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) in 10-20% (1-4). Despite advances in knowledge and treatment of AP, the identification of patients with clinically severe disease on admission remains difficult (1) and the mortality in several series continues to be around 20% (2,5).

The factors responsible for high mortality in patients with SAP are organ failure (OF) and pancreatic necrosis (6,7). The reported incidence of OF in SAP varies from 28-76 % (5,8,9). The occurrence of organ dysfunction and progressive organ failure has a major impact on outcome. Many patients who succumb to AP within the first two weeks of disease onset do so from overwhelming multiorgan failure (10,11). Other studies have also reported that prognosis deteriorated with an increase in number of organs involved (12,13). Banks and Freeman (14) studied the correlation between mortality and organ failure in patients with acute pancreatitis and documented a median mortality of 3% in patients with single organ failure and 47% in patients with multisystem organ failure. Another study documented that the overall mortality (47.8%) correlated with the number of organs failing (6). The definition of multiorgan failure is broad and encompasses transient to persistent or severe multiorgan failure that requires critical care support (15). Patients with persistent organ failure have a higher mortality as compared to patients where organ failure resolves (16). Johnson and Hial (17) showed that patients with OF that resolved within 48 hours(transient) have a low risk of complications and death in comparison to patients who have persistent organ failure(OF persisting for 3 or more days) and have a greater than one in three risk of fatal outcome. Information regarding the prediction of persistent organ failure in patients with acute pancreatitis is not available (18).

One of the factors linked to the development of OF is the extent of pancreatic necrosis. Some workers have found a correlation between the extent of necrosis and OF (19). The question of the relationship between infected necrosis and OF remains unsettled. There is no consistency in the literature on whether organ failure or infected necrosis is the main determinant of severity in acute pancreatitis. The aim of study was to study the occurrence of organ failure in acute pancreatitis and determine the influence of organ failure on mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis.

Materials and Methods

This study was a prospective study under taken during 18 months (December 2011 to May 2013) in the Departments of Gastroenterology, General Surgery and Medical Intensive Care Unit in Fortis Hospital, Mohali, Punjab, a 260 bedded multispecialty tertiary care hospital in Northern India.

The study sample included all consecutive patients diagnosed with acute pancreatitis referred to Gastroenterology or General surgery units fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All the patients were assessed for demographic profile and detailed symptom profile. After a detailed clinical examination relevant investigations were repeated as and when required. Patients were monitored for the presence and severity of organ failure every day during the first week, subsequent local complications, subsequent episodes of sepsis, and death or other outcomes during the same hospital admission.

Organ failure was defined as per modified multiple organ failure score (MMOFS). Transient organ failure was defined as organ failure present for less than 48 hours, and persistent organ failure was recorded when organ failure was present for more than 48 hours, where day 0 was the day of entry to the study and day one started at 8.00am on the day after entry. The course in hospital and final outcome was recorded. Cross tabulations were made with outcome, in particular with mortality.

Statistical Analysis. The data are presented as mean ± SD or median and interquartile range, as appropriate. The Mann- Whitney U-test was used for statistical analysis of skewed continuous variables and ordered categorical variables. For normally distributed data The t-test was applied. Pearson χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used for analysis of categorical variables with two categories. A p value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All calculations were performed using SPSS® version 15 (Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences, Chicago, IL).

Results

The study was comprised of 61 patients who met the inclusion criteria with diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. The study group was further divided as per organ failure into three groups:

- No organ failure (NOF)

- Transient organ failure ( < 48 hrs) (TOF)

- Persistent organ failure ( > 48 hrs) (POF)

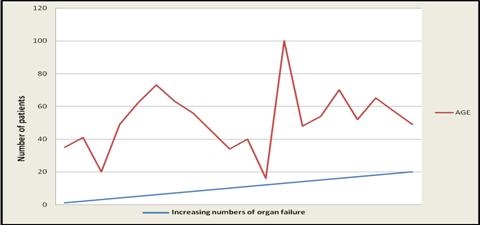

Demographic Distribution. The mean age of the patients was 46.5 years. The majority of patients were in the age group of 30-50 years. In this study the youngest patient was 17 years old and oldest was 87 years old (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Age distribution with increased number of organs involvement.

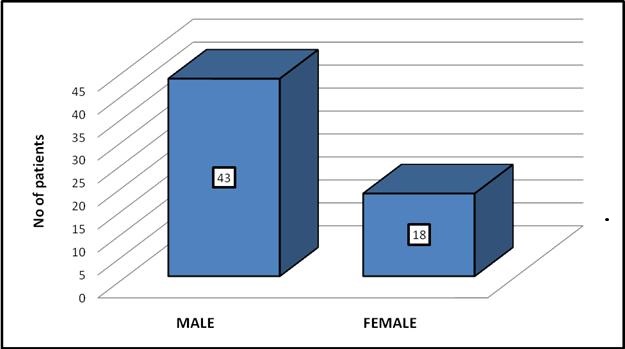

The male to female ratio was found to be 2.4:1 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Sex distribution.

Male predominance was found in all groups (53.3 %, 81.8%, and 90 % in the no organ, transient and persistent organ failure group respectively).

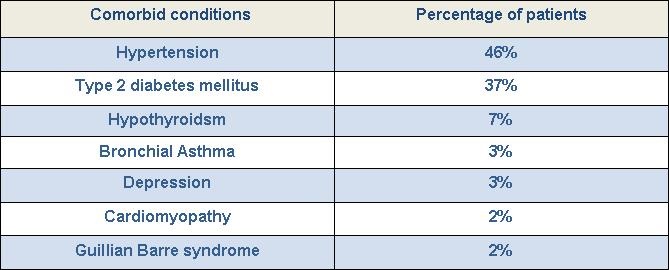

Comorbid Conditions. A majority of the patients (38) in our study group had no associated comorbid conditions while 23 patients (37.8%) had a previous comorbid condition. Hypertension was the most common comorbid condition, seen in almost 31 % of the patients at the time of admission. Type 2 diabetes was the second most common condition noted in 24.6%, followed by hypothyroidism (4.9%), asthma, depression, cardiomyopathy and Guillain-Barré syndrome in 1.6% each (Table 1).

Table 1. Comorbid conditions associated in our study group.

We could not find any association between co morbidities and mortality as 9 (62.9%) deaths occurred in the no comorbidity group as compared to 4 (30.8%) deaths in the co morbidities group (p=0.880).

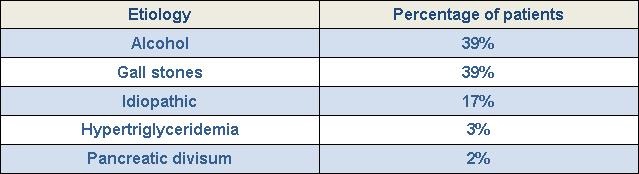

Etiology. The most common etiologies of pancreatitis in our study group were alcohol and gall stones (n=24, 39% each) (Table 2).

Table 2. Etiology of acute pancreatitis.

Other causes were idiopathic (n=10, 17%), hypertriglyceridemia (n=2, 3%) and pancreatic divisum (n=1, 2%).

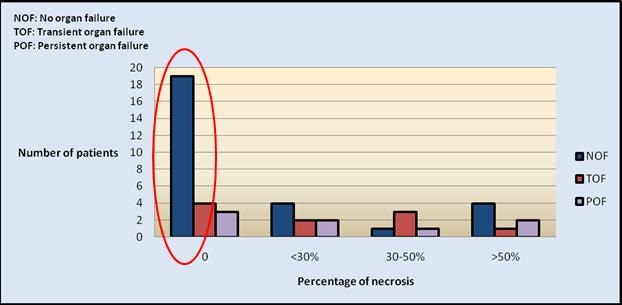

Percentage of Necrosis and Organ Failure. The percentage of necrosis on radiological imaging (in 46 patients) was evaluated for its relationship with organ failure. In the NOF group 19 (63.3%) patients had no necrosis (0%), 4 (13.3%) patients had <30% necrosis, 1 (3.3%) had 30-50% and 4 (13.3%) had >50% necrosis (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Relation between organ failure and pancreatic necrosis.

In the TOF group, 4 (36.4%) patients revealed no necrosis on contrast-enhanced computerized tomography (CECT) of the abdomen, <30% necrosis in 2 (18.2%) patients, 30-50% necrosis in 3 (27.3%) and >50% in 1 (9.1%) patient (Figure 3).

In POF group no necrosis was detected in 3 (15%) patients, <30 % in 2 (10%), 30-50% in 1 (5%) and >50% in 2 (10%) patients. The relationship between the amount of necrosis was directly related with incidence of organ failure and this correlation was found to be statistically significant (Figure 3).

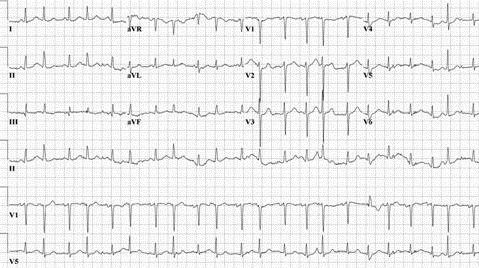

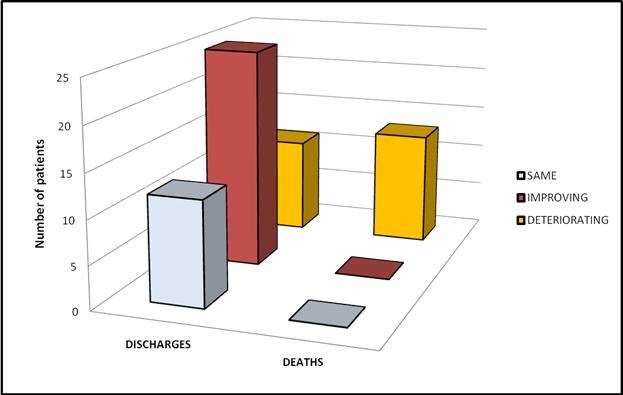

MMOFS and Mortality. We divided our study in 3 groups, no organ failure, transient (<48 hrs) and persistent (>48 hrs) organ failure to understand the nature and dynamics of organ failure. Groups were further divided in early onset (<7days), late onset (>7days). Organ failure was calculated by the Modified multiorgan failure score (MMOFS). Daily MMOFS was calculated in all patients up to 7 days. MMOFS difference was calculated by MMOFS 7 (MMOFS at day 7) – MMOFS 1 (at the time of admission). On the basis of MMOFS difference groups were further divided into same (if difference was 0), improving (if deference was negative value), or deteriorating (if deference was a positive value) groups (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Comparison of outcome with MMOFS difference.

MMOFS difference was found to be highly significantly (ANOVA, p<0.001 each) correlated with organ failures and outcome. In our study no deaths occurred in the transient OF groups (early transient, late transient and transient deteriorating). We attributed this to the dynamics that transient OF could resolve with treatment and had a better outcome than persistent OF. Among the 13 deaths reported in our study, 46.2 % were in the early (<7 days) OF group compared to the late (>7 days) OF group (20%).

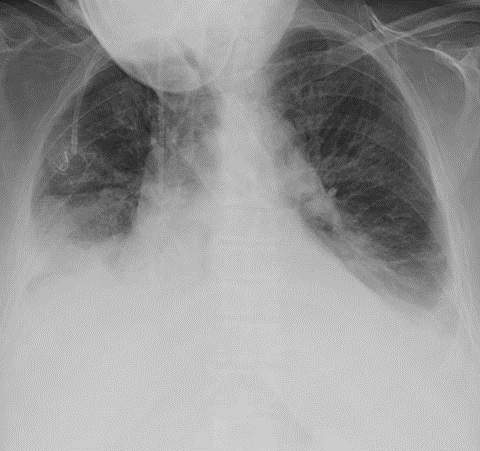

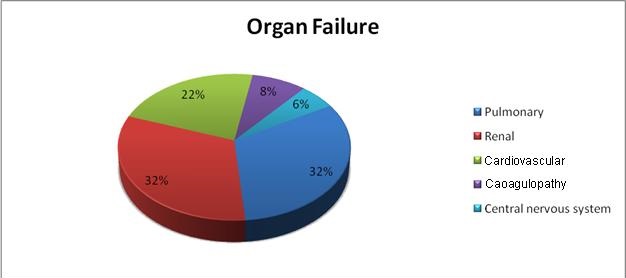

Organ Involvement. Pulmonary and renal failures were the most common organ involvements noted among our study group (32% each). This was followed by cardiovascular system (22%), coagulation system (8%) and central nervous system (6%) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Organ failure by system.

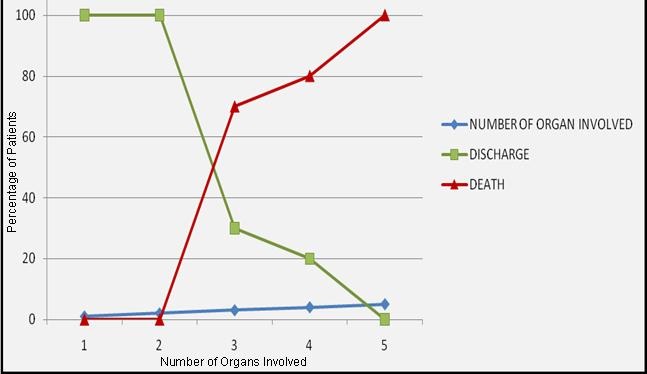

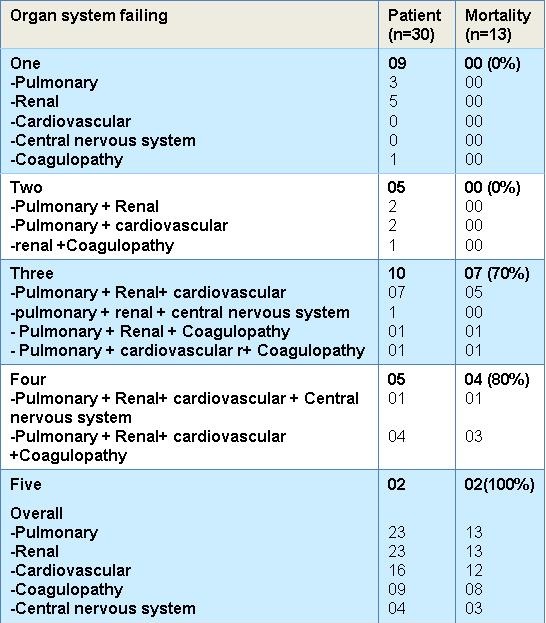

Organ involvement and mortality. Fourteen (46.4%) patients had one or two OF and 17 (56.6%) had more than two OF (table 3). Comparison of the number of organ failures to mortality was statically significant (p<0.001) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Outcome in patients with increasing organ involvement.

We found that there was an increase in incidence of mortality with an increase in the number of organs involved. There were no deaths in patients with up to two organ failures; it increased with increasing number of organs involved (Table 3).

Table 3. Organ failure and mortality.

The mortality rate was 70% (n=7) with three organ involvement, 80 % (n=4) with four and 100% with five OF.

Discussion

Severe acute pancreatitis is a systemic disease and characterized by acute onset and rapid progression, with a high incidence of complications and serious morbidity (20). An international multidisciplinary classification of acute pancreatitis severity is based on local and systemic determinants of severity. The local determinants relate to presence of pancreatic necrosis, and whether the necrosis is infected or sterile. The systemic determinants relate to whether there is organ failure or not, and if present, whether it is transient or persistent. The presence of both infected pancreatic necrosis and persistent organ failure has a greater impact on severity than either determinant alone. Based on these principles, the severity is classified as mild, moderate, severe or critical (21).The three most common systems involved are renal, lung, and cardiovascular system. Respiratory complications are frequent in acute pancreatitis and respiratory dysfunction is a major component of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (22,23). In a population based study, 15.05% of patients with AP had a diagnosis of acute renal failure (24).

The present study showed that the difference in age was not significantly different between the groups. There are some studies which showed an association between advancing age as a predictor of organ failure and mortality. Wig et al. (6) studied 161 patients and concluded that age of the patients was a risk factor for multiple organ failure. Li et al. (25) studied 181 patients with SAP and found a correlation of age with OF (<.001). Frey et al26 also showed that the number of complications was positively correlated with the age of patients. Older age and number of complications were strong predictors of organ failure among patients with SAP. Though we recorded a higher incidence of organ failures and mortality in a younger age group of 40-45, the difference was attributed to a small number of patients above 65 years in our study as compared to studies done in the western world.

The bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis (BISAP) score represents a simple way to identify patients at risk for increased mortality and the development of intermediate markers of severity within 24 hours of presentation. In our series the BISAP score was significantly associated (p<.001) with organ failure as well as survival (p<.001). We found 9 out of 13 deaths in the >3 score group and four deaths at a BISAP score of 2 as compared to zero mortality in the BISAP score 1 and 0 group. Kim et al. (27) also compared BISAP, the serum procalcitonin (PCT), and other multifactorial scoring systems simultaneously, concluded that BISAP is more accurate for predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis than the serum procalcitonin, APACHE-II, Glasgow, and modified CT severity index (MCTSI) scores. Chen et al. (28) evaluated the accuracy of BISAP in predicting the severity and prognosis of acute pancreatitis (AP) in 497 Chinese patients. They conclude that BISAP score is valuable in predicting the severity of AP and prognoses of SAP in Chinese patients.

Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of pancreatic necrosis and peripancreatic collections. CT assessment correlates with the clinical course of the disease and recognized variables of disease severity. We ordered CECT in all patients on the second or third day after admission rather than at the time of admission. Additional contrast-enhanced CT scans were ordered at intervals during the hospitalization to detect and monitor the course of intra-abdominal complications of acute pancreatitis, such as the development of organized necrosis, pseudocysts, and vascular complications including pseudoaneurysms. In our study CT severity index (CTSI) > 7 at admission did not correlate well with organ failure or mortality (p=NS), although the percentage of necrosis had significant correlation with organ failure. Our results are similar to many studies reported in the literature. Simchuk et al. (29) performed a study on 268 patients with acute pancreatitis. They concluded CTSI > 5 correlated significantly with death. Similar results were also obtained by Leung et al. (30) on 121 patients studied retrospectively, and they concluded that CTSI is superior to Ranson’s score and APACHE II score in predicting outcome in pancreatitis. However a few studies found no association between grade of necrosis and outcome of pancreatitis. Shinzeki et al. (31) did not find any correlation between necrosis evident on CECT at admission and outcome of SAP (p=0.061). Another study by Lankisch et al. (32) also did not find any correlation between necrosis and organ failure.

In our study pulmonary and renal were the most common organ failures observed (32% each). The total number of organ failures at admission was also significantly different in both groups (p=0.001), however none of the organ failures independently proved to be a significant predictor of mortality. MMOFS difference was found to be highly significantly correlated with organ failures and outcome. Among the 13 deaths reported in our study, 46.2 % were in the early (<7 days) OF group compared to the late (>7 days) OF group (20%). Our series also showed comparable results with other studies suggesting that early organ failure is the major predictor of poor outcome MMOFS difference was found to be highly significantly (ANOVA, p<0.001 each) correlated with organ failures and outcome. In our study no deaths occurred in the transient OF groups (early transient, late transient and transient deteriorating). We attributed this to the dynamics that transient OF could resolve with treatment and had a better outcome than persistent OF. Among the 13 deaths reported in our study, 46.2 % were in the early (<7 days) OF group compared to the late (>7 days) OF group (20%). Our series also showed comparable results with other studies suggesting that early organ failure is the major predictor of poor outcome (p=0.002) compared to late organ failure (p=0.400).

We found that early persistent OF had a 66.6% mortality as compared to persistent deteriorating organ failure which also had a very high mortality (72.2%). Very few studies have reported on the dynamics of OF with MMOFS. Johnson et al. (19) in a study of 290 patients with SAP had 116 patients with no OF and 147 patients with OF at the time of admission subdivided those with OF into those with persistent (OF lasting for>48 hours) and transient (OF lasting for<48hours) organ failure. Mortality was 36.3% in persistent and 5% in transient OF group. No patients without OF died.

On analysis of the 13 patients who expired, 4 patients died early (<7 days) and 9 deaths were late (>7 days). OF was the main cause of death in both groups, however all patients with sepsis died later. In the study of Yang et al. (33) the most important and common cause of death for patients with fulminant pancreatitis was multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, which usually was the consequence of systemic inflammation response syndrome in the early stage, and severe infection in the later stage, respectively.

Conclusions

Patients with persistent organ failure have a higher mortality. Early persisting and deteriorating organ failure had the worst outcome of among patients with acute pancreatitis. There was an increase in mortality with increasing number of organs involved. The extent of necrosis was directly related with the incidence of organ failure.

References

-

Bollen TL, Singh VK, Maurer R, Repas K, van Es HW, Banks PA, Mortele KJ. A comparative evaluation of radiologic and clinical scoring system in the early prediction of severity in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:612-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Zyromski NJ. Necrotizing pancreatitis in 2010: an unifinished odyssey. Ann Surg. 2010; 251:794-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Kylanpaa L, Rakonczay Z, O' Reilly DA. The clinical course of acute pancreatitis and the inflammatory mediators that drive it. Int J inflammation. 2012;2012:360685. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Refinetti RA, Martinez R. Necrotising pancreatitis: update and when to operate. Clinical Medicine and Diagnostics. 2012;2:20-6.

-

Poves Prim I, Fabregat Pous J, García Borobia FJ, Jorba Martí R, Figueras Felip J, Jaurrieta Mas E. Early onset of organ failure is the best predictor of mortality in acute pancreatitis. Rev Esp Enform Dig (Madrid). 2004;96:705-13. [PubMed]

-

Wig JD, Bharathy KG, Kochhar R, Yadav TD, Kudari AK, Doley RP, Gupta V, Babu YR. Correlates of organ failure in severe acute pancreatitis. JOP. 2009;10:271-5. [PubMed]

-

Mole DJ, Olabi B, Robinson V, Garden OJ, Parks RW. Incidence of individual organ dysfunction in fatal acute pancreatitis: analysis of 1024 death records. HPB (Oxford). 2009;11:166-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Halonen KI, Pettilä V, Leppäniemi AK, Kemppainen EA, Puolakkainen PA, Haapiainen RK. multiple organ dysfunction associated with severe acute pancreatitis. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1274-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Lytras D, Manes K, Triantopoulou C, Paraskeva C, Delis S, Avgerinos C, Dervenis C. Persistent early organ failure: defining the high-risk group of patients with severe acute pancreatitis? Pancreas. 2008;36:249-54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Vege SS, Gardner TB, Chari ST, Munukuti P, Pearson RK, Clain JE, Petersen BT, Baron TH, Farnell MB, Sarr MG. Low mortality and high morbidity in severe acute pancreatitis without organ failure: a case for revising the Atlanta classification to include moderately severe acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroentrol. 2009;104:710-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Frey CF, Zhou H, Harvey DJ, White RH. The incidence and case fatality rates of acute biliary, alcoholic and idiopathic pancreatitis in California 1994-2001. Pancreas. 2006;33:336-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Buter A, Imrie CW, Carter CR, Evans S, McKay CJ. Dynamic nature of early organ dysfunction determines outcome in acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2002;89:298-302. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Mofidi R, Duff MD, Wigmore SJ, Madhavan KK, Garden OJ, Parks RW. Association between early systemic inflammatory response, severity of multiorgan dysfunction and death in acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2006:93:738-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Banks PA, Freeman ML. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2379-2400. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Pandol SJ, Saliya AK, Imrine CW, Banks PA. Acute pancreatitis :Bench to bed side : Gasroentrology. 2007;133:1127-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

de-Madaria E, Soler-Sala G, Lopez-Font I, Zapater P, Martínez J, Gómez-Escolar L, Sánchez-Fortún C, Sempere L, Pérez-López J, Lluís F, Pérez-Mateo M. Update of Atlanta classification of severity of acute pancreatitis: should a moderate category be included. Pancreatology. 2010;10: 613-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Johnson CD, Abu-Hilal M. Persistent organ failure during the first week as a marker of fatal outcome in acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2004;53;1340-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Mentula P, Kylanpaa ML, Kemppainen E. Early prediction of organ failure by combined markers in patients with acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg 2005; 92: 68-75. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Garg PK, Madan K, Pande GK, Khanna S, Sathyanarayan G, Bohidar NP, Tandon RK. Association of extent and infection of pancreatic necrosis with organ failure and death in acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Clin Gastroentrol Hepatol. 2005;3:159-66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Pavlidis P, Crichton S, Lemmich Smith J, Morrison D, Atkinson S, Wyncoll D, Ostermann M. improved outcome of severe acute pancreatitis in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Res Pract. 2013;2013:897107. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Dellinger EP, Forsmark CE, Layer P, et al. Determinant- based classification of acute pancreatitis severity: an international multidisciplinary consultation. Ann Surg. 2012;256:875-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Chan YP, Ning JW, Je F. Establishment of critical period of severe acute pancreatitis associated lung injury. Hepatobiliary Pancreas Dis Int. 2009;8: 535-40. [PubMed]

-

Pastor CM, Matthy MA, Frossard JL. Pancreatitis associated acute lung injury – new insights. Chest. 2003;124: 2341-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Lin HY, Lai JI, Lai YC, Lin PC, Chang SC, Tang GJ.Acute renal failure in severe pancreatitis: a population based study. Ups J Med Sci. 2011;116:155-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Li XY, Wang XB, Liu XF, Li SG. Prevelence and risk factor of organ failure in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. World J Emerg Med. 2010;1(3):201-4. [PubMed]

-

Frey C, Zhou H, Harvey D. Co-morbidity is a strong predictor of early death andmulti-organ system failure among patients with acute pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:733-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Kim BG, Noh MH, Ryu CH, Nam HS, Woo SM, Ryu SH, Jang JS, Lee JH, Choi SR, Park BH. A comparison of the BISAP score and serum procalcitonin for predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis. Korean J Intern Med. 2013;28:322-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Chen L, Lu G, Zhou Q, Zhan Q. Evaluation of the BISAP score in predicting severity and prognoses of acute pancreatitis in Chinese patients. Int Surg. 2013;98(1):6-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Simchuk EJ, Traverso LW, Nukui Y, Kozarek RA. Computed tomography severity index is a predictor of outcomes for severe pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 2000;179:352-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Leung TK, Lee CM, Lin SY, Chen HC, Wang HJ, Shen LK, Chen YY. Balthazar computed tomography severity index is superior to Ranson criteria and APACHE II scoring system in predicting acute pancreatitis outcome. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6049-52. [PubMed]

-

Shinzeki M, Ueda T, Takeyama Y, Yasuda T, Matsumura N, Sawa H, Nakajima T, Matsumoto I, Fujita T, Ajiki T, Fujino Y, Kuroda Y. Predictors of early death in severe acute pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:152-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Lankisch PG, Pflichthofer D, Lehnick D. No strict correlation between necrosis and organ failyre in acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2000;20:319-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Yang XN, Guo J, Lin ZQ, Huang L, Jin T, Wu W, Wen L, Zhang ZD, Xia Q, Hu WM. The study on causes of death in fulminant pancreatitis at early stage and late stage. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2011;42(5):686-90. [PubMed]

Reference as: Maheshwari N, Kumar A, Iqbal ZA, Mandal AK, Vyas A, Wig JD. Organ failure in acute pancreatitis and its impact on outcome in critical care. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2015;10(5):253-64. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc055-15 PDF