Tacrolimus-Associated Diabetic Ketoacidosis: A Case Report and Literature Review

Tuesday, February 27, 2018 at 8:00AM

Tuesday, February 27, 2018 at 8:00AM Stella Pak, MD1

Megan Hirschbeck, BS2

Damian Valencia, MD1

Victor Valencia, BS3

Yusuf Askaroglu, BS2

Dexter Nye, BS2

Adam Fershko, MD2

1Departments of Medicine, Kettering Medical Center, Kettering, Ohio USA

2Department of Medicine, Boonshoft School of Medicine, Dayton, Ohio USA

3Department of Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois USA

Abstract

Post-transplant diabetes mellitus is a well-established adverse effect of calcineurin inhibitors, such as tacrolimus and cyclosporine. Failure to identify and manage this side effect in a timely manner could lead to life-threatening complications like diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). To the best of our knowledge, this is the seventh published case of an uncommon but severe, and potentially fatal, adverse effect from tacrolimus after renal transplantation. The purpose of this case report is to add to the scant body of literature on tacrolimus-induced diabetes following renal transplantation.

Introduction

New-onset diabetes mellitus after transplantation (NODAT) is a well-established adverse effect of calcineurin inhibitors, such as tacrolimus and cyclosporine. NODAT has been reported to occur in 13.4% of patients after solid organ transplantation, with a higher incidence in patients receiving tacrolimus than cyclosporine, 16.6% and 9.8% respectively (1). Failure to identify and manage this side effect in a timely manner could lead to life-threatening complications like diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). Currently, only seven reported cases, including this report, of NODAT with DKA exist in the English literature. This case report describes a patient who developed tacrolimus-induced diabetic ketoacidosis three months after receiving renal transplantation.

Case Description

The patient is a 44-year-old Caucasian male with no past medical history of diabetes mellitus who presented with diabetic ketoacidosis three months after receiving a deceased-donor kidney transplant for end stage renal disease secondary to autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. The patient’s immunosuppressive regimen included tacrolimus, mycophenolate and low dose prednisone (5 mg daily). The patient initially presented with complaints of nausea and polyuria. He did not have a family history of diabetes mellitus. Physical examination was unremarkable except for a body mass index (BMI) of 27 kg/m2. Laboratory work-up revealed hyperglycemia with a glucose of 493; an anion gap metabolic acidosis with pH at 7.32 and bicarbonate at 19; significant ketosis; and ketonuria. Glycated hemoglobin (hemoglobin A1c) was 9.8 % compared to 4.8% thirty days post-transplant. Tacrolimus trough level was in the therapeutic range. Glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD-65) autoantibodies were negative. The patient received intravenous fluids, a bolus of intravenous insulin followed by a continuous insulin infusion which was soon switched to subcutaneous insulin. Upon resolution of the patients DKA, the total daily maintenance insulin requirements were approximately 40 units. The patient received diabetic education and was discharged home.

Discussion

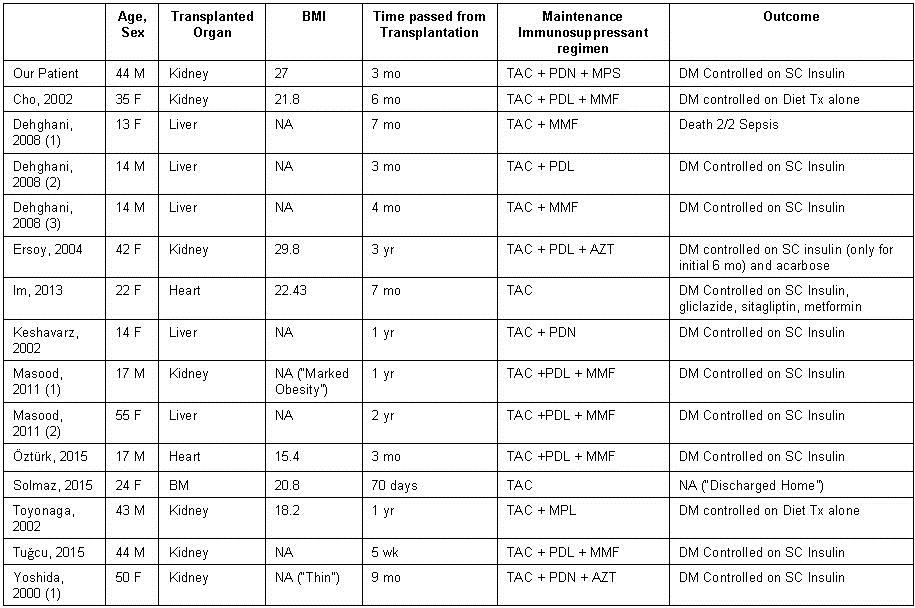

At the time of writing this report, there were only six reported cases of NODAT following the use of cyclosporine inhibitors such as tacrolimus which are summarized in table 1 (2-7).

Table 1. Summary of the seven reported cases focused on clinical presentation and management.

BMI: body-mass-index; M: male; F: female; BM: bone marrow; TAC: tacrolimus; MPL: methylprednisolone; PDL: prednisolone; PDN: prednisone; MPS: mycophenolate sodium; MMF: mycophenolate mofetil; AZT: azathioprine; CYC: cyclosporine; RG: random glucose; FG: fasting glucose; Yr: year; Mo: month; Wk: week; NA: not available; DM: diabetes mellitus; Tx: therapy

Five of the now seven reported cases detail the development of diabetic ketoacidosis at least six months after renal transplantation (2-5, 7). In contrast, our case and the case detailed by Dr. Tuğcu and his colleagues describe the presentation of DKA and new onset diabetes within three months of transplantation (6).

Maintenance immunosuppressive therapy is essential to prevent organ rejection in renal transplant recipients. Calcineurin inhibitors play an integral role in most immunosuppressive regimens, with tacrolimus being the preferred agent over cyclosporine, as several studies show lower incidence of acute rejection with its use (1). Both calcineurin inhibitors are known to cause toxicity to pancreatic islet beta cells and may also directly affect transcriptional regulation of insulin expression (5). Evidence suggests that tacrolimus causes greater incidence of severe swelling-vacuolization, endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis of pancreatic islet beta cells when compared to cyclosporine (8). Tacrolimus associated diabetogenic effects threaten the health and longevity of the allograft by predisposing the recipients to microvascular and macrovascular diabetic complications which subsequently reduce allograft survival.

The development of diabetes mellitus Type 1 with ketoacidosis in patients on therapeutic tacrolimus with no risk factors for diabetes highlights the need for alternative immunosuppressive agents which won’t compromise long-term survival of the patients’ allograft. This case report highlights the importance of regular fasting blood glucose monitoring in patients on a tacrolimus-regimen for immunosuppression in order to prevent the life-threatening complication of diabetic ketoacidosis and subsequent allograft rejection in the setting of uncontrolled diabetes mellitus.

Post-transplant diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality, by approximately 10 %, among renal transplant patients. The reduction in survival rate due to post-transplant diabetes mellitus is largely due to cardiovascular disease, such as coronary artery disease and congestive heart failure (9). Given the negative impact of NODAT in the survival of renal transplant patients, preventive efforts should be made to minimize risk factors. Known risk factors for NODAT include obesity, hepatitis C, African American race, Hispanic ethnicity, family history of diabetes mellitus, use of calcineurin inhibitor and/or corticosteroid. Early identification of patients at high risk for NODAT would help tailor immunotherapeutic suppressant regimen and to aggressively manage modifiable risk factors for NODAT (10, 11). The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) recommends proactive prescreening of all post-transplant patients for NODAT, with measurement of fast plasma glucose at least once per week for first 4 weeks post-transplant. Afterwards, post-transplant patients should have fasting plasma glucose test at 3, 6, 12 months, at 1-year intervals thereafter. Glycated hemoglobin (Hemoglobin A1C) is recommended to be check at 3 months following the transplant procedure (12).

Calcineurin inhibitors, including tacrolimus and cyclosporine, inhibit calcineurin in β-cells of the pancreas. Inhibition of calcineurin indirectly suppresses expression of genes involved in insulin production. In particular, adverse glycemic effect occurs with a greater incidence with tacrolimus than cyclosporine. This is thought to be mostly due to tacrolimus-induced changes in the level of β-cell enriched transcription factors, forkhead box protein O1 (FoxO1) and v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog A (MafA). Tacrolimus selectively promotes nuclear translocation of FoxO1 and cytoplasmic location of MafA. These modulations of transcript factors then cause β-cell dysfunction, attributing to the development of NODAT (13).

Conclusion

Considering the potentially devastating complication of allograft compromise due to undiagnosed NODAT, it is imperative that clinicians monitor patients for signs of impaired glucose metabolism, specifically those who are treated with tacrolimus.

References

- Heisel O, Heisel R, Balshaw R, Keown P. New onset diabetes mellitus in patients receiving calcineurin inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:583-95. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho YM, Park KS, Jung HS, Kim YS, Kim SY, Lee HK. A case showing complete insulin independence after severe diabetic ketoacidosis associated with tacrolimus treatment. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1664. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ersoy A, Ersoy C, Tekce H, Yavascaoglu I, Dilek K. Diabetic ketoacidosis following development of de novo diabetes in renal transplant recipient associated with tacrolimus. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:1407-10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masood MQ, Rabbani M, Jafri W, Habib M, Saleem T. Diabetic ketoacidosis associated with tacrolimus in solid organ transplant recipients. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61:288-90. [PubMed]

- Toyonaga T, Kondo T, Miyamura N, et al. Sudden onset of diabetes with ketoacidosis in a patient treated with FK506/tacrolimus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2002;56:13-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed

- Tuğcu M, Kasapoglu U, Boynuegri B, et al. Tacrolimus-Induced Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Effect of Switching to Everolimus: A Case Report. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:1528-30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida EM, Buczkowski AK, Sirrs SM, et al. Post-transplant diabetic ketoacidosis--a possible consequence of immunosuppression with calcineurin inhibiting agents: a case series. Transpl Int. 2000;13:69-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangel EB. Tacrolimus in pancreas transplant: a focus on toxicity, diabetogenic effect and drug-drug interactions. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2014;10: 1585-605. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shivaswamy V, Boerner B, Larsen J. Post-transplant diabetes mellitus: causes, treatment, and impact on outcomes. Endocr Rev. 2016;37(1):37-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasiske BL, Snyder JJ, Gilbertson D, Matus AJ. Diabetes mellitus after kidney transplantation in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:178-85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karavelioglu D, Baysal C, Ozdemir N et al. Impact of HCV infection on the development of post transplantation diabetes mellitus in renal allograft recipients. Transplantation Proc. 2000;32;(3):561-2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson A, Davidson J, Dotta F et al. Guidelines for the treatment and management of new onset of diabetes after transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2005;19:291-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trianes J, Rodriguez-Rodriguez AE, Brito-Cassilas Y, et al. Deciphering tacrolimus-induced toxicity in pancreatic β cells. Am J Transplant. 2017;17: 2829-40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Pak S, Hirschbeck M, Valencia D, Valencia V, Askaroglu Y, Nye D, Fershko A. Tacrolimus-associated diabetic ketoacidosis: a case report and literature review. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2018;16(2):103-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc015-18 PDF